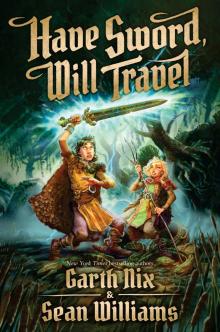

Have Sword, Will Travel Read online

Title Page

Dedication

Map

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Epilogue

About the Authors

Copyright

Odo and Eleanor did not set out to find their destiny. At best, they were hoping for eels.

“I’ve never seen the river so low before,” said Odo as he climbed down the banks and began to trudge through the thick, reddish mud. He’d walked along and waded in the same stretch of the Silverrun for what felt like every single day of his life. Like his days, the river was always much the same. But now, there was a lot more mud and a lot less river.

“Father says it never has been so low,” said Eleanor absently. She was already a few steps ahead of him — but that was no surprise. She was always a few steps ahead of him, he felt. Odo watched as his best friend stopped and looked intently at one of the puddles next to the thin, knee-deep stream that was all that remained of the once-rushing river. Before Odo could say anything else, she lunged with her spear and lifted out a writhing eel firmly stuck on two of its three sharp prongs.

“Got it!” she cried.

“I noticed,” said Odo. He was impressed, but it was more fun to make Eleanor think he wasn’t. He took the snapping eel off the spear, his strong fingers holding it firmly despite its slime. Then he put it in the wicker basket he held and strapped the lid back on. There were already four eels inside awaiting the fifth.

“When the river is this low, it’s very bad for the mill,” Odo went on. “There’s not enough water to turn the wheel. We’re grinding with the small millstone now, turning it by hand.”

“I wondered why you sneaked away,” said Eleanor. She headed downstream. “Let’s go to Dragonfoot Hole. All the eels will be gathering there, I reckon.”

“I didn’t sneak away!” protested Odo. He was the seventh child of the village miller — and even if there had been seventy more kids in the family, there would always be work to do. “I did my share this morning!”

“I know — you’re very good,” said Eleanor with a grin, in a way that made good almost sound like an insult. Her father was the village apothecary, and though she did help him with some things, he by and large let her do what she liked. What Eleanor liked the most was looking for adventure. In the village of Lenburh, this meant spearing eels, shooting rabbits with her bow, or scrumping apples from the bad-tempered Wicstun family. Which was fun for about three minutes … Eleanor wanted more. Her mother had been a soldier knighted on the field of her last battle, and Eleanor planned to follow in her footsteps, if she could find someone to train her. In the becoming a knight part, not the dying in battle.

Odo didn’t know what he wanted to be. He would be thirteen next spring, and at that age most people were already doing whatever they would be doing for the rest of their lives. He had to decide soon if he wanted to apprentice with someone instead of his mother, the miller.

“Do you reckon we’ll all have to move?” he asked Eleanor, eyeing the shallows and the mud. “I mean if the water dries up completely?”

“Yep!” said Eleanor brightly, spearing another eel. She quite liked the idea of heading off into the unknown.

“The river will come back, though,” said Odo, basketing the eel without even thinking about it. “It’s been raining lately.”

“But isn’t that what makes it all so strange?” Eleanor asked as she peered around the edges of the biggest sinkhole on the river. “It’s been raining and the river is still drying up. Look, what’s that?”

Odo looked. Dragonfoot Hole was a deep depression that exactly resembled the imprint of a mighty clawed foot. Odo had never seen it so clearly before. Normally he would have had to dive down to the river bottom holding his breath, but now the water hardly flowed over his large bare feet.

Odo could see three eels swimming just below the surface where Eleanor was pointing. Then he caught the faint gleam of something shiny sticking out of the muddy riverbed.

“Metal,” he said. “Probably an old horseshoe or something. I’ll get it.”

He knelt and reached down into the water.

Eleanor could make out a long silver shape through the murk. “Doesn’t look like a horseshoe,” she commented.

“Well, I know that now. Ow!” He pulled his hand back and looked at the thin line of blood on his finger. “It’s sharp!”

Eleanor knew she should tend to her best friend’s wound. But she couldn’t take her eyes off of what they’d found.

“It’s a sword,” she said breathlessly. She started to reach for it herself, but Odo grabbed her wrist.

“Careful!” he warned. “I only just touched the tip of the blade, and look!”

He held up his injured finger, showing Eleanor the cut. A single drop of blood welled up and slid across his flour-stained fingernail, falling into the water above the submerged weapon. For a moment the drop stayed together, then it broke apart and swirled away.

“Press on it; that’ll stop the bleeding,” said Eleanor, unimpressed. She’d helped her father sew up many really serious wounds, like last week when Aelbar the farmer had run over his foot with a plough. “I’ll just lever this out.”

She reversed her eel-spear, pushed it into the mud under the silvery blade, and heaved down.

The sharp, pointy end of the sword came out of the mud with a loud squelching sound.

“It’s not even rusty!” exclaimed Eleanor in wonder. She moved the spear shaft farther along, eager to free the rest of the weapon from the mud. “Can I have it? You’ve never wanted a sword.”

“I guess so,” said Odo. He’d been pressing on his cut finger, but stopped to have a look and see if the cut was still bleeding. It was, and another big drop of blood fell. This time, it didn’t fall in the water. It fell on the tip of the sword and ran down the narrow gutter in the middle of the blade.

“Blood.”

The single word was not spoken by either Odo or Eleanor, but by a deep, male voice that was a little scratchy, like it belonged to someone woken from a very deep sleep.

Eleanor and Odo looked around and then at each other. They were alone in Dragonfoot Hole. There was no one standing on the high banks on either side and no one upstream or downstream either, and this was a straight stretch, at least fifty yards of empty river.

“Blood.”

The voice was stronger now. More awake. It sounded like it was coming from someone right next to the two children. Someone they couldn’t see.

Odo stepped back and clenched his fists. He was very big for his age, and strong from all his heavy work in the mill.

Eleanor reversed her eel-spear again, holding it ready. She wasn’t big, but she was very, very quick, as the eels knew to their cost.

“BLOOD!”

Odo and Eleanor screamed as the sword erupted out of the water. It shot into the air as if wrenched from the mud by some invisible warrior, and hung there unsupported, water cascading from its golden hilt and sharkskin grip, the sun making the huge emerald in its pommel gleam.

“Who has woken me from my rest?” roared the voice.

There was no doubt where that voice was coming from now.

The sword.

Eleanor struck at the weapon, catching the blade between the prongs of her eel-spear. Twisting, she forced the sword back down into the river with a huge splash.

“Run, Odo! I’ll try to hold —”

The spear juddered in her hand, moving violently despite her best efforts to keep it still. Odo grabbed hold as well, but that only seemed to make the sword angrier. It suddenly twisted in the water, broke free, and chopped up the shaft of the eel-spear, reducing it to six-inch bits in a flurry of lightning-fast blows.

Eleanor flung the last bit of the spear away and turned to run. Odo threw the basket of eels at the sword, but the sword dodged it easily. It bashed Eleanor with the flat of its blade, knocking her down to the mud, then whisked around in front of Odo, hovering there with its incredibly sharp point a finger-width from the hollow of Odo’s throat.

Odo stood completely still, his eyes wide in terror.

“Did you wake me from my rest?” The sword wasn’t shouting now. It almost sounded normal, like someone stopping at the mill to ask Odo when they could get their wheat ground.

“Um, I’m not … not sure,” said Odo. “We were hunting eels and we saw your … you … shining there …”

“Blood woke me,” said the sword. “The blood of a true knight, for naught else could raise me from my slumber. I have need of such a knight. Whose blood has awoken me?”

Odo knew the answer to this question. And if there was any possible way to get out of giving the sword the answer, he would have. But he had a feeling the sword already knew.

“Ah, well, I suppose that was my blood,” said Odo. “But I’m not a knight. I’m just one of the miller’s children —”

“Do you mean to kill us, sword?” Eleanor interrupted, sitting up in the mud and wiping at her face. Odo sent her an urgent “don’t give it ideas” look, which she ignored.

“I do not make war upon innocents,” said the sword, sounding faintly affronted. It backed up a little, still hovering in the air like a huge, shining, and frighteningly dangerous wasp. “What is your name, miller’s son?”

“Odo. And this is my friend Eleanor.”

“And you are not a knight.”

“Er, no.”

“But your blood woke me, and only a true knight’s blood could have done so,” mused the sword, as though working through a difficult problem.

“If you say so.” Odo made a slight gesture with his fingers to Eleanor. She knew this meant run away while the sword’s talking. But she ignored him again, stood up, and faced the sword, her hands on her hips.

“You’re one of those magic swords, aren’t you?” Eleanor wasn’t afraid now the sword was just talking, not attacking. “Like in the stories. Sir Wulfstan had one called Bright Talon. What’s your name?”

“Hildebrand Shining Foebiter,” said the sword proudly. “You might know me better as Biter. No doubt you have heard the many stories told of me. More than this so-called Bright Talon, I’m sure.”

Odo and Eleanor exchanged a quick glance. Eleanor gave a slight shrug. She’d never heard of Hildebrand Shining Foebiter, and she was much more interested in old legends than Odo was.

“We live in a small village,” said Odo. “We don’t get to hear many stories. Uh, can we go now?”

“No,” said Biter. “I must think. My rest could only have been broken by the taste of a true knight’s blood. Yet you say you are not a true knight. Are you sure?”

“Yes,” said Odo. “I’m not any sort of knight.”

“Does it have to be a proper knight?” Eleanor asked. “What if it’s someone who’s going to be a knight one day? The daughter, say, of a knight. Wouldn’t that be enough?”

“I … slept for many years,” said the sword. “My memories are somewhat clouded. But I am sure … fairly sure … about the detail of the true knight.”

“Fine.” Eleanor couldn’t help sounding a little miffed. “If you need a ‘true’ knight, there is old Sir Halfdan at the manor. We could take you to him, I suppose.”

“No,” said Biter. “I can only be woken by a true knight. Yet you are not a knight. This situation cannot be allowed.”

Odo didn’t like the sound of that. “Why don’t you just go back to sleep and forget we ever found you —” he pleaded.

“Kneel!” ordered the sword. He rose higher in the air and angled back, as if to strike at Odo’s neck.

“At least let Eleanor go.”

“And go too while you’re at it,” added Eleanor urgently.

“Kneel, I say!”

Odo knelt down in the mud, babbling.

“Please, spare Eleanor. It was my fault you got woken up —”

The blade came whistling down, slowed at the last moment, and turned sideways, slapping Odo on the left shoulder. Odo flinched, but the killing blow didn’t fall. Instead, the blade whipped up above his head and then tapped him on the right shoulder.

“Rise, Sir Odo!” called out the sword, pulling away and hanging dazzling in the sunlight.

“Sir … what?”

“Now you are a knight,” said the sword. “All is properly in order.”

“What?!” Eleanor cried out, her voice caught high and tremulous in her throat. “This is so unfair! I’m the one who wants to be a knight. I’m a better fighter than Odo too.”

“She is,” Odo agreed. He started to stand up, then stopped as he realized his legs were shaking and might not hold him. His neck still felt bare and cold where he’d expected the sword to slice.

“You can be Sir Odo’s squire,” said Biter to Eleanor, which didn’t make her feel any better at all. “Every knight must have a squire. But enough of this chatter. Doubtless I have been awoken to combat great evil or dire threat. Tell me what it is.”

Eleanor helped Odo up. Neither had any idea what to say. Just moments ago they had been hunting eels, and now one of them was a knight and the other a squire … and a talking sword had gotten it completely the wrong way around.

“You are too afraid even to speak of it,” Biter pressed. “Some fell beast creeps at night and steals children and livestock? A sinister steward in midnight-dark raiment demands tributes beyond endurance? Come, Sir Odo, when you wield Biter you need fear none of these!”

“It’s not that,” said Odo. “We … that is … there’s simply no great evil threatening us.”

“Or dire threat,” said Eleanor. “Least I can’t think of one …”

“There must be something,” said Biter in an aggrieved voice. “Take my hilt, Sir Knight, we will sally forth and essay the matter. Your hand, Sir Odo. To me.”

Odo gingerly held out his open palm. The sword flashed up and around in a circle, the sharkskin grip slapping against the boy’s hand. Odo closed his fingers around it and held the sword away from his body as if it were an actual shark.

“Hold tighter!” called Biter. Odo gripped harder and felt even more worried than he had a few moments before.

“What does ‘essay the matter’ mean?” Odo said out of the corner of his mouth to Eleanor.

“Look into things,” replied Eleanor. And as soon as she said it out loud, she thought, I like the sound of that. Her whole life, she’d been waiting to sally forth. More than anyone else in their town, she was ready to essay matters. All these actions led to a much bigger, brighter, and very attractive word …

Adventure.

Immediately, Eleanor’s mood turned surprisingly cheerful, despite the mud all over her and the presence of the magic sword that was straining in Odo’s grip like a dog on a lead.

“This isn’t goo

d,” whispered Odo. “How am I going to get rid of this sword?”

“Why would you want to, you big saddle-goose?” asked Eleanor, her eyes bright. “This is an adventure! At last!”

Now Odo didn’t know what scared him more — the bizarre sword in his hand or Eleanor’s even more bizarre enthusiasm.

“But I don’t want an adventure!” he protested. “Or to be a knight!”

Eleanor slapped him on the back. He took a step that turned into a stumbling run up the riverbank as Biter pulled him forward.

“But you’ve got both!” Eleanor called out. Then she laughed and added, “Lead on, Sir Odo!”

Odo had no illusions as to who was leading who. The sword pulled him along the path so hard he almost overbalanced, reminding him of the time the rival team of shepherds’ children had almost beaten the miller’s children during the annual tug-of-war competition on the Lenburh green. Then, as now, he felt that at any moment his feet would slip out from under him and deposit him on his backside in front of the whole village.

The first witnesses, it appeared, would be Aaric and Addyson, the unbearable twin sons of Lenburh’s baker.

“Look here!” Aaric scoffed, sauntering over. “It’s Odd Odo and Eelanor playing soldiers — and they’ve stolen Sir Halfdan’s sword to do it!”

Eleanor flushed in anger and embarrassment. Aaric and Addyson had doughy skin and hair as white as flour — they looked like loaves brought out of the oven too soon — and their favorite occupation was taunting Eleanor and Odo, knowing full well the two friends had been forbidden to fight them.

“We’re not playing,” she told them. “And that isn’t Sir Halfdan’s sword. It’s … he’s Sir Odo’s … and he doesn’t take kindly to the likes of you.”

“Sir who?” The twins clutched their bellies and howled with laughter. “You’d better take that sword back before Sir Halfdan or the reeve sees you with it.”

“Disrespectful knaves!” Odo felt the words vibrate up the sword and along his arm even as Biter lunged forward.

Aaric and Addyson fell backward with cries of fright.

“Odo!” Aaric shrieked. “What are you —?”

The sword slashed the air in front of Aaric’s nose and would have cleaved his skull in half if Odo hadn’t yanked the weapon back with his entire body weight. Setting his heels deep, he kept Biter at bay as the twin bakers stared in shock.

The Ragwitch

The Ragwitch Newt's Emerald

Newt's Emerald Grim Tuesday

Grim Tuesday Sabriel

Sabriel Mister Monday

Mister Monday The Missing

The Missing The Fall

The Fall A Confusion of Princes

A Confusion of Princes Troubletwisters

Troubletwisters Lirael

Lirael Lord Sunday

Lord Sunday Clariel

Clariel Drowned Wednesday

Drowned Wednesday Shade's Children

Shade's Children The Violet Keystone

The Violet Keystone Abhorsen

Abhorsen The Monster

The Monster The Creature in the Case

The Creature in the Case To Hold the Bridge

To Hold the Bridge Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar

Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Above the Veil

Above the Veil Aenir

Aenir Mystery of the Golden Card

Mystery of the Golden Card Superior Saturday

Superior Saturday Sir Thursday

Sir Thursday Castle

Castle Lady Friday

Lady Friday Into Battle

Into Battle Dislocation Space

Dislocation Space Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1)

Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1) Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1

Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1 The Left-Handed Booksellers of London

The Left-Handed Booksellers of London Novel - A Confusion of Princes

Novel - A Confusion of Princes One Beastly Beast

One Beastly Beast A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3

A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3 Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2

Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2 Have Sword, Will Travel

Have Sword, Will Travel Fire Above, Fire Below

Fire Above, Fire Below Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case

Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case The Monster (Troubletwisters)

The Monster (Troubletwisters) Across the Wall

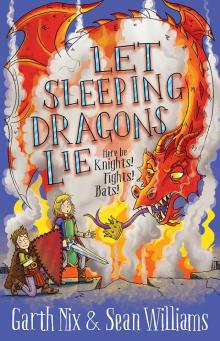

Across the Wall Let Sleeping Dragons Lie

Let Sleeping Dragons Lie![[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/abhorsen_03a_-_across_the_wall_preview.jpg) [Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall

[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall