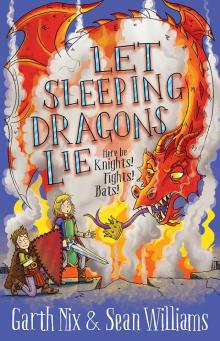

Let Sleeping Dragons Lie Read online

First published by Allen & Unwin in 2018

Copyright © Garth Nix & Sean Williams 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or ten per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 74343 993 7

eBook ISBN 978 1 76087 003 4

For teaching resources, explore

www.allenandunwin.com/resources/for-teachers

Cover illustration copyright © 2018 by Cherie Zamazing

Map copyright © 2018 by D.M. Cornish

Cover design by Nick Stern

Text design by Ian Butterworth

To Anna, Thomas, Edward, and all my family and friends.

— Garth Nix

To Amanda, and all our friends and family, with gratitude and love.

— Sean Williams

CONTENTS

MAP

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

EPILOGUE

ALSO BY THE AUTHORS

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

‘Bilewolves!’

‘Help us!’

‘Help me!’

‘Aarrgh, no, no—’

The shouts and screams grew louder as Sir Odo and Sir Eleanor raced towards the village green, their magical, self-willed swords, Biter and Runnel, almost lifting them from the ground in their own eagerness to join the combat. Well behind them came Addyson and Aaric, the baker’s twin boys, who had come in a panic to tell them the village was under attack.

Above all the human sounds of fear and fighting, a terrible howling came again, from more than one bestial throat.

‘Slower!’ panted Odo as they reached the back of the village inn, the Sign of the Silver Fleece, or the Grey Sheep, as it was nicknamed, since the sign had long since faded. ‘We must be clever. Stay shoulder to shoulder, advance with care.’

‘Nay, we must charge at once!’ roared Biter, even as his sister sword snapped, ‘I agree, Sir Odo.’

‘I do too,’ said Eleanor, slowing so her much larger and less fleet-of-foot friend could catch up. When he was level with her, she moved closer so they were indeed shoulder to shoulder, their swords held in the guard position.

Together, and ready, they rounded the corner of the inn.

A terrible scene met their eyes. Some forty paces away, four enormous, shaggy, wolflike creatures, each the size of a small horse, stood at bay opposite a man and a woman. The people were hunters or trappers, judging by their leather armour and well-travelled boots, although they were quite old to be in that trade. Both looked to be at least fifty.

The man had a cloth of shining gold tied around his eyes, which perhaps explained Addyson’s panicked description of ‘a blind king’ being attacked by the bilewolves. The cloth did give the impression of a crown.

Blind or not, king or not, the man wielded his steel-shod staff with a brilliance that made Odo gasp. The weapon was a blur, leaping out to punch one bilewolf’s snout, then jab another’s forefoot. The woman was equally adept, though she wielded a curved sword, the blade moving swiftly and smoothly as she danced with it, the bilewolves slow and clumsy partners. Close to the inn on the edge of the green, three villagers lay dead or seriously wounded, their torn and jagged clothes still smoking from the bilewolves’ acid-spewing jaws. Eleanor’s father, the herbalist Symon, was bent over the closest victim, frantically trying to stem the flow of blood from a wound. He looked up for a second at his daughter, but did not speak, turning instantly back to his work.

Odo grasped the situation immediately. Only the two old warriors kept the bilewolves away from the wounded and the rest of the defenceless villagers. But the two were outnumbered and, despite their skill, overmatched by the sheer size and ferocity of the animals.

‘Forward!’ Odo shouted, and he and Eleanor marched together.

‘For Lenburh!’ shouted Eleanor.

Odo knew from the slightest tremor in Eleanor’s voice that she was afraid, though no one else would be able to tell. He was afraid as well. They were only twelve years old and had been knights for little over a month, but he knew the fear would not stop Eleanor, and it wouldn’t stop him either.

They did not expect their war cries to be answered, but off to the right came a shout: ‘Forward for Lenburh!’ A horse came galloping across the green, the ancient warhorse of Sir Halfdan, who, like the master who rode it, had not been in battle for twenty years or more. True to its training, the warhorse held straight for the bilewolves, despite their terrible stench and formidable snarls. Sir Halfdan, despite age and infirmity, was rock-solid in the saddle, a lance couched under his arm. He had not had time to put on any armour save his helmet and a gauntlet. He still wore the nightgown that was his usual garb these days, and his one foot was still clad in a velvet slipper.

A bilewolf turned towards the galloping horse and charged, leaping at the last moment to avoid Sir Halfdan’s lowering lance. But the old knight knew that trick and flicked the point up, taking the beast in the shoulder, the steel point punching deep. Bilewolf shrieked, the lance snapped, and then horse, knight, and dying bilewolf collided and went flying.

At the same time, one of the three remaining bilewolves bounded up on the back of one of its fellows and leaped high over the head of the blind staff-wielder. The man jumped upon his companion’s shoulders and punched up at the bilewolf’s belly, but the beast had launched itself too well. The staff merely struck its wiry tail, severing it midway along as the bilewolf flew past them.

Odo and Eleanor rushed across the green, expecting the falling bilewolf to attack them and the unprotected villagers behind. But it ignored them, spinning about as it landed to strike at the two warriors once again, dark blood spraying from its injured tail. The blind man jumped down with the deftness of a travelling acrobat and stood back-to-back with the woman. Together they turned in a circle, staff and sword blurring to hold the bilewolves at bay.

Odo slowed and edged cautiously closer, wondering how the blindfolded man had struck so precisely with his staff. Meanwhile, Eleanor narrowed her eyes, seeking a way into the battle.

‘Take the one to my right!’ shouted the swordswoman to Odo and Eleanor, her voice strong and well used to command. ‘It is already lamed!’

‘Sixth and Fourth Stance!’ said Eleanor. ‘You high, me low.’

They moved in perfect synchrony, as they’d practised, Odo stepping left and out, Biter held

above his head to strike in a slanting downwards blow, as Eleanor stretched out low with a lunge at the bilewolf ’s right front leg, which it already favoured.

The bilewolf bunched itself to leap up at Odo, choosing the bigger target. But Runnel’s sharp point cut through its leg even as it sprang. It fell sideways, yelping, and Biter came down to separate its massive head from its body, the sword twisting to avoid a spray of bile from the snapping jaws. Both young knights struck again to be sure it was dead, and then swung about to move to the next target.

But the remaining two bilewolves were already slain, one with a crushed skull and the other with a sliced-open throat. All four carcasses lay steaming, the grass beneath them turning black and smoking where the acidic drops fell from their jaws.

‘Sir Halfdan!’ cried Eleanor. The old knight lay motionless upon the ground, the haft of his broken lance still couched under his arm. His warhorse lay near him, unable to get up. It raised its head and whinnied, as if in answer to some trumpet no one else could hear, but the effort was too much. Its head fell heavily back and did not move again.

‘Wait!’ Odo called as Eleanor started towards the old knight. ‘Do you see any more bilewolves?’

The swordswoman answered him. She and the man still stood back-to-back, their weapons ready, as if they expected another attack at any moment.

Or they didn’t trust Odo and Eleanor.

‘There will be none,’ she said. ‘They hunt in fours and are jealous of their prey. You are knights of the realm?’

‘Uh, we’re knights, but not … exactly of the realm, I don’t think,’ said Odo. ‘I am Sir Odo.’

‘And I, Sir Eleanor.’ It gave her a small thrill to say that, although there were more pressing matters to consider. ‘If there are no more bilewolves, we must help Sir Halfdan while my father attends to the others—’

‘One moment, Sir Eleanor,’ snapped the woman. ‘How are you knights, but not exactly of the realm?’

‘It’s a long story,’ said Odo. ‘We were knighted by the dragon Quenwulf—’

‘Quenwulf?’ asked the woman. Her expression shifted to one minutely more relaxed. ‘Was it she who gifted you with the enchanted swords you bear?’

‘No!’ said Biter. He was still not entirely convinced he shouldn’t be a dragonslaying sword.

‘Uh, no,’ said Odo. ‘We found them. Like I said, it is a long story—’

‘Best saved for later,’ said the blind man. His voice was even more used to command than the woman’s. ‘Take me to the fallen knight, Hundred. Sir Eleanor, did you say he was Sir Halfdan?’

‘Yes, Sir Halfdan holds the manor here,’ Eleanor told the man as she studied the woman more closely. Hundred was a very strange name, but perhaps it was apt for a very strange person. In addition to the curved sword she still held at the ready, Eleanor noticed she had a series of small knives sheathed along each forearm, and unusual pouches on her belt. The backs of her dark-skinned hands were white with dozens of scars, like Eleanor’s mother’s hands – not wounds from claws or teeth, but weapon marks. A sign of many years of combat and practice.

‘Sir, we should go on at once,’ protested Hundred. ‘No,’ said the man. He turned to face where Sir Halfdan lay and began to walk towards him, using his staff to tap the ground. After a moment, Hundred went ahead of him, and the man stopped tapping and followed her footfalls.

‘He must have amazing hearing,’ whispered Eleanor to Odo.

‘I have well-trained ears,’ said the man without turning his head.

Odo and Eleanor exchanged glances, then hurried after the odd duo.

Sir Halfdan lay on his back, not moving. His helmet, too big for him, had tipped forward over his face. Hundred knelt by his side and gently removed it. The old knight’s eyes opened as she did so, surprising everyone, for he had seemed already dead.

‘Sir Halfdan,’ said the blind man, bending over him. Sir Halfdan blinked rheumily, and his jaw fell. ‘Sire,’ he whispered. ‘Can it be?’

The old knight tried to lift his head and arm, but could not do so. The blind man knelt by him and closed his own hand over Halfdan’s gauntlet.

‘I remember when you held the bridge at Holmfirth,’ said the blind man. ‘In the second year of my reign. None so brave as Sir Halfdan. You remember the song Veran wrote? She will have to write another verse.’

‘That was long ago,’ whispered Halfdan.

‘Time has no dominion over the brave.’

‘I thought … we thought you dead, sire.’

Eleanor mouthed ‘sire’ at Odo and hitched one shoulder in question. He shrugged, unable to explain what was going on. But looking at the blind man in profile, there was something familiar about the shape of his face, that beaky nose, the set chin.

‘I gave up the throne,’ said the man. He touched his golden blindfold. ‘When I lost my sight, I thought I could no longer rule. I was wrong. Blindness makes a man a fool no more than a crown makes him king.’

At the word king, Odo suddenly remembered why the old man’s profile looked familiar.

It was on the old silver pennies he counted at the mill.

Eleanor had the same realisation. They both sank together to the earth, their hauberks jangling. Odo went down on his right knee and Eleanor on her left. They looked at each other worriedly and started to spring up again to change knees, before Hundred glared at them and made a sign to be still.

‘My time is done, sire,’ said Sir Halfdan. There was a rattle in his voice. He glanced over at his horse. ‘Old Thunderer has gone ahead, and I must follow …’

He paused for a moment, the effort of gathering his thoughts, of speaking, evident on his face.

‘I commend to you, sire … two most brave knights … Sir Eleanor and Sir Odo. They—’

Whatever he was going to say next was lost. At that moment old Sir Halfdan died. Egda the First – for the blind man was certainly the former king of Tofte, who had abdicated ten years ago – gripped Sir Halfdan’s shoulder in farewell and stood up, turning towards the kneeling Odo and Eleanor.

‘He was a great and noble knight,’ he said. ‘The Hero of Holmfirth Bridge, and even then he must have been over forty. To think of him slaying a bilewolf at the age of ninety!’

‘We didn’t know he was a hero,’ said Eleanor uncomfortably. She was thinking about some of the names she had called him because he was slow getting organised for their journey east, to be introduced to the royal court. And how some people in the village had mocked him behind his back for having only one foot, though they would never dare do so to his face. ‘He was just our knight. He’s been here so long … um … sorry, should I say “sire”, or is it “Your Highness”?’

‘I am not a king,’ said the blind man. ‘I have been simply Egda these last ten years.’

‘Sir Egda,’ said Hundred sharply. ‘You may refer to his grace as “sir” or “sire”.’

‘Now, now, Hundred,’ said Egda. He smiled faintly, exposing two rows of white, even teeth. ‘Hundred was the captain of my guard and has certain ideas about maintaining my former station. I wish to hear how you were made knights by the dragon Quenwulf, but first there is work to be done. The bilewolves must be burned. Are the wounded villagers attended to? I hear pain, but also gentle soothing.’

Eleanor looked over to where the wounded were now being lifted to be carried inside the inn. Her father was assisted by several other villagers, including the midwife Rowena, who often worked with him.

‘They are being tended to by my father, who is a healer and herbalist, sir,’ she said.

‘I’ll gather wood to burn the bilewolves,’ said Odo. ‘Addyson and Aaric can help, if it please you, sir.’

‘I do not command here,’ said Egda mildly. ‘Who is Sir Halfdan’s heir? Has he a daughter or son to take up his lands and sword? Or, given his age, grandchildren, perhaps?’

‘There’s no one,’ said Eleanor, frowning. She looked across at where the wounded or dead were being taken into

the inn. ‘Only his squire, Bordan, and I think he was one of the three other people the bilewolves—’

‘They sought to help us,’ said Egda. ‘Would that they were less brave.’

‘I warned them away,’ said Hundred harshly. ‘If they had kept back, they would have been in no danger.’

‘Only if the bilewolves were after you in particular,’ said Odo, made curious by her comment.

‘This is not a matter for you, boy,’ said Hundred. ‘Sire, we must be on our—’

‘No,’ interrupted the former king. He didn’t seem happy with the way Hundred was addressing Odo’s inquiries. ‘We will rest here tonight, not camp in the wilds. Sir Halfdan was my father’s knight before he served me. We must show proper respect, see him put to rest. Also, I want to hear the story of these two swords – who are strangely quiet now, though I heard them in the battle.’

‘I merely wait for my knight to introduce me, sir,’ said Biter. He sounded aggrieved. ‘He is new to his estate and I am still teaching him manners.’

‘Oh,’ said Odo. He held up Biter, hilt first. ‘This is Hildebrand Shining Foebiter. Often called Biter.’

‘And my sword is Reynfrida Sharp-point Flamecutter, or Runnel for short,’ said Eleanor.

‘Greetings, sir,’ said Runnel.

‘And welcome, sire,’ added Biter, not wanting to be left out.

Egda nodded. ‘Well then. Sir Odo, to the burning of the beasts. Sir Eleanor, if you would introduce me to your father and other notables in the village, we must order … that is, suggest the arrangements to lay Sir Halfdan to rest. Hundred, cast about for any sign of other unfriendly beasts.’

‘Sire!’ protested Hundred. ‘I cannot leave you unprotected.’

‘Sir Eleanor, would you give me your arm?’ asked Egda. ‘Sir Odo, would you take care to listen and come should I call for aid?’

‘Yes, sir!’ said Odo and Eleanor together.

‘You see,’ said Egda to the frowning Hundred. ‘I have two knights to guard me. Come, let us be about our business!’

He strode off confidently towards the inn, tapping once more with his staff and hardly holding Eleanor’s crooked arm at all. Odo stared after him. When he looked back to see what Hundred was doing, he was surprised to find himself alone. In just a few seconds, the elderly warrior had disappeared from the middle of the green!

The Ragwitch

The Ragwitch Newt's Emerald

Newt's Emerald Grim Tuesday

Grim Tuesday Sabriel

Sabriel Mister Monday

Mister Monday The Missing

The Missing The Fall

The Fall A Confusion of Princes

A Confusion of Princes Troubletwisters

Troubletwisters Lirael

Lirael Lord Sunday

Lord Sunday Clariel

Clariel Drowned Wednesday

Drowned Wednesday Shade's Children

Shade's Children The Violet Keystone

The Violet Keystone Abhorsen

Abhorsen The Monster

The Monster The Creature in the Case

The Creature in the Case To Hold the Bridge

To Hold the Bridge Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar

Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Above the Veil

Above the Veil Aenir

Aenir Mystery of the Golden Card

Mystery of the Golden Card Superior Saturday

Superior Saturday Sir Thursday

Sir Thursday Castle

Castle Lady Friday

Lady Friday Into Battle

Into Battle Dislocation Space

Dislocation Space Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1)

Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1) Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1

Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1 The Left-Handed Booksellers of London

The Left-Handed Booksellers of London Novel - A Confusion of Princes

Novel - A Confusion of Princes One Beastly Beast

One Beastly Beast A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3

A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3 Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2

Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2 Have Sword, Will Travel

Have Sword, Will Travel Fire Above, Fire Below

Fire Above, Fire Below Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case

Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case The Monster (Troubletwisters)

The Monster (Troubletwisters) Across the Wall

Across the Wall Let Sleeping Dragons Lie

Let Sleeping Dragons Lie![[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/abhorsen_03a_-_across_the_wall_preview.jpg) [Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall

[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall