Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2 Read online

Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe

( Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz - 2 )

Garth Nix

Garth Nix was born in 1963 in Melbourne, Australia, and grew up in Canberra. When he turned nineteen he left to drive around the UK in a beat-up Austin with a boot full of books and a Silver-Reed typewriter. Despite a wheel literally falling off the car, he survived to return to Australia and study at the University of Canberra. He has since worked in a bookshop, as a book publicist, a publisher’s sales representative, an editor, a literary agent, and as a public relations and marketing consultant. He was also a part-time soldier in the Australian Army Reserve, but now writes full-time.

His first story was published in 1984 and was followed by novels The Ragwitch, Sabriel, Shade’s Children, Lirael, Abhorsen, the six-book YA fantasy series “The Seventh Tower,” and most recently the seven-book “The Keys to the Kingdom” series. He lives in Sydney with his wife and their two children.

Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe

Garth Nix

“Remind me why the pirates won’t sink us with cannon fire at long range,” said Sir Hereward as he lazed back against the bow of the skiff, his scarlet-sleeved arms trailing far enough over the side to get his twice-folded-back cuffs and hands completely drenched, with occasional splashes going down his neck and back as well. He enjoyed the sensation, for the water in these eastern seas was warm, the swell gentle, and the boat was making a good four or five knots, reaching on a twelve knot breeze.

“For the first part, this skiff formerly belonged to Annim Tel, the pirate’s agent in Kerebad,” said Mister Fitz. Despite being only three feet, six and a half inches tall and currently lacking even the extra height afforded by his favourite hat, the puppet was easily handling both tiller and main sheet of their small craft. “For the second part, we are both clad in red, the colour favoured by the pirates of this archipelagic trail, so they will account us as brethren until proven otherwise. For the third part, any decent perspective glass will bring close to their view the chest that lies lashed on the thwart there, and they will want to examine it, rather than blow it to smithereens.”

“Unless they’re drunk, which is highly probable,” said Hereward cheerfully. He lifted his arms out of the water and shook his hands, being careful not to wet the tarred canvas bag at his feet that held his small armoury. Given the mission at hand, he had not brought any of his usual, highly identifiable weapons. Instead the bag held a mere four snaphance pistols of quite ordinary though serviceable make, an oiled leather bag of powder, a box of shot, and a blued steel main gauche in a sharkskin scabbard. A sheathed mortuary sword lay across the top of the bag, its half-basket hilt at Hereward’s feet.

He had left his armour behind at the inn where they had met the messenger from the Council of the Treaty for the Safety of the World, and though he was currently enjoying the light air upon his skin, and was optimistic by nature, Hereward couldn’t help reflect that a scarlet shirt, leather breeches and sea boots were not going to be much protection if the drunken pirates aboard the xebec they were sailing towards chose to conduct some musketry exercise.

Not that any amount of leather and proof steel would help if they happened to hit the chest. Even Mister Fitz’s sorcery could not help them in that circumstance, though he might be able to employ some sorcery to deflect bullets or small shot from both boat and chest.

Mister Fitz looked, and was currently dressed in the puffy-trousered raiment of one of the self-willed puppets that were made long ago in a gentler age to play merry tunes, declaim epic poetry and generally entertain. This belied his true nature and most people or other beings who encountered the puppet other than casually did not find him entertaining at all. While his full sewing desk was back at the inn with Hereward’s gear, the puppet still had several esoteric needles concealed under the red bandanna that was tightly strapped on his pumpkin-sized papier-mâché head, and he was possibly one of the greatest practitioners of his chosen art still to walk—or sail—the known world.

“We’re in range of the bow-chasers,” noted Hereward. Casually, he rolled over to lie on his stomach, so only his head was visible over the bow. “Keep her head on.”

“I have enumerated three excellent reasons why they will not fire upon us,” said Mister Fitz, but he pulled the tiller a little and let out the main sheet, the skiff’s sails billowing as it ran with the wind, so that it would bear down directly on the bow of the anchored xebec, allowing the pirates no opportunity for a full broadside. “In any case, the bow-chasers are not even manned.”

Hereward squinted. Without his artillery glass he couldn’t clearly see what was occurring on deck, but he trusted Fitz’s superior vision.

“Oh well, maybe they won’t shoot us out of hand,” he said. “At least not at first. Remind me of my supposed name and title?”

“Martin Suresword, Terror of the Syndical Sea.”

“Ludicrous,” said Hereward. “I doubt I can say it, let alone carry on the pretense of being such a fellow.”

“There is a pirate of that name, though I believe he was rarely addressed by his preferred title,” said Mister Fitz. “Or perhaps I should say there was such a pirate, up until some months ago. He was large and blond, as you are, and the Syndical Sea is extremely distant, so it is a suitable cognomen for you to assume.”

“And you? Farnolio, wasn’t it?”

“Farolio,” corrected Fitz. “An entertainer fallen on hard times.”

“How can a puppet fall on hard times?” asked Hereward. He did not look back, as some movement on the bow of the xebec fixed his attention. He hoped it was not a gun crew making ready.

“It is not uncommon for a puppet to lose their singing voice,” said Fitz. “If their throat was made with a reed, rather than a silver pipe, the sorcery will only hold for five or six hundred years.”

“Your throat, I suppose, is silver?”

“An admixture of several metals,” said Fitz. “Silver being the most ordinary. I stand corrected on one of my earlier predictions, by the way.”

“What?”

“They are going to fire,” said Fitz, and he pushed the tiller away, the skiff’s mainsail flapping as it heeled to starboard. A few seconds later, a small cannon ball splashed down forty or fifty yards to port.

“Keep her steady!” ordered Hereward. “We’re as like to steer into a ball as not.”

“I think there will only be the one shot,” said the puppet. “The fellow who fired it is now being beaten with a musket stock.

Hereward shielded his eyes with his hand to get a better look. The sun was hot in these parts, and glaring off the water. But they were close enough now that he could clearly see a small red-clad crowd gathered near the bow, and in the middle of it, a surprisingly slight pirate was beating the living daylights out of someone who was now crouched—or who had fallen—on the deck.

“Can you make out a name anywhere on the vessel?” Hereward asked.

“I cannot,” answered Fitz. “But her gun ports are black, there is a remnant of yellow striping on the rails of her quarterdeck and though the figurehead has been partially shot off, it is clearly a rampant sea-cat. This accords with Annim Tel’s description, and is the vessel we seek. She is the Sea-Cat, captained by one Romola Fury. I suspect it is she who has clubbed the firer of the bow-chaser to the deck.”

“A women pirate,” mused Hereward. “Did Annim Tel mention whether she is comely?”

“I can see for myself that you would think her passing fair,” said Fitz, his tone suddenly

severe. “Which has no bearing on the task that lies ahead.”

“Save that it may make the company of these pirates more pleasant,” said Hereward. “Would you say we are now close enough to hail?”

“Indeed,” said Fitz.

Hereward stood up, pressed his knees against the top strakes of the bow to keep his balance, and cupped his hands around his mouth.

“Ahoy Sea-Cat!” he shouted. “Permission for two brethren to come aboard?”

There was a brief commotion near the bow, most of the crowd moving purposefully to the main deck. Only two pirates remained on the bow: the slight figure, who now they were closer they could see was female and so was almost certainly Captain Fury, and a tub-chested giant of a man who stood behind her. A crumpled body lay at their feet.

The huge pirate bent to listen to some quiet words from Fury, then filling his lungs to an extent that threatened to burst the buttons of his scarlet waistcoat, answered the hail with a shout that carried much farther than Hereward’s.

“Come aboard then, cullies! Port-side if you please.”

Mister Fitz leaned on the tiller and hauled in the main sheet, the skiff turning wide, the intention being to circle in off the port-side of the xebec and then turn bow-first into the wind and drop the sail. If properly executed, the skiff would lose way and bump gently up against the pirate ship. If not, they would run into the vessel, damage the skiff and be a laughing stock.

This was the reason Mister Fitz had the helm. Somewhere in his long past, the puppet had served at sea for several decades, and his wooden limbs were well-salted, his experience clearly remembered and his instincts true.

Hereward, for his part, had served as a gunner aboard a frigate of the Kahlian Mercantile Alliance for a year when he was fifteen and though that lay some ten years behind him, he had since had some shorter-lived nautical adventures and was thus well able to pass himself off as a seaman aboard a fair-sized ship. But he was not a great sailor of small boats and he hastened to follow Mister Fitz’s quiet commands to lower sail and prepare to fend off with an oar as they coasted to a stop next to the anchored Sea-Cat.

In the event, no fending off was required, but Hereward took a thrown line from the xebec to make the skiff fast alongside, while Fitz secured the head- and main-sail. With the swell so slight, the ship at anchor, and being a xebec low in the waist, it was then an easy matter to climb aboard, using the gun ports and chain-plates as foot- and hand-holds, Hereward only slightly hampered by his sword. He left the pistols in the skiff.

Pirates sauntered and swaggered across the deck to form two rough lines as Hereward and Fitz found their feet. Though they did not have weapons drawn, it was very much a gauntlet, the men and women of the Sea-Cat eyeing their visitors with suspicion. Though he did not wonder at the time, presuming it the norm among pirates, Hereward noted that the men in particular were ill-favoured, disfigured, or both. Fitz saw this too, and marked it as a matter for further investigation.

Romola Fury stepped down the short ladder from the forecastle deck to the waist and stood at the open end of the double line of pirates. The red waistcoated bully stood behind, but Hereward hardly noticed him. Though she was sadly lacking in the facial scars necessary for him to consider her a true beauty, Fury was indeed comely, and there was a hint of a powder burn on one high cheek-bone that accentuated her natural charms. She wore a fine blue silk coat embroidered with leaping sea-cats, without a shirt. As her coat was only loosely buttoned, Hereward found his attention very much focussed upon her. Belatedly, he remembered his instructions, and gave a flamboyant but unstructured wave of his open hand, a gesture meant to be a salute.

“Well met, Captain! Martin Suresword and the dread puppet Farolio, formerly of the Anodyne Pain, brothers in good standing of the chapter of the Syndical Sea.”

Fury raised one eyebrow and tilted her head a little to the side, the long reddish hair on the unshaved half of her head momentarily catching the breeze. Hereward kept his eyes on her, and tried to look relaxed, though he was ready to dive aside, headbutt a path through the gauntlet of pirates, circle behind the mizzen, draw his sword and hold off the attack long enough for Fitz to wreak his havoc . . .

“You’re a long way from the Syndical Sea, Captain Suresword,” Fury finally replied. Her voice was strangely pitched and throaty, and Fitz thought it might be the effects of an acid or alkaline burn to the tissues of the throat. “What brings you to these waters, and to the Sea-Cat? In Annim Tel’s craft, no less, with a tasty-looking chest across the thwarts?”

She made no sign, but something in her tone or perhaps in the words themselves made the two lines of pirates relax and the atmosphere of incipient violence ease.

“A proposition,” replied Hereward. “For the mutual benefit of all.”

Fury smiled and strolled down the deck, her large enforcer at her heels. She paused in front of Hereward, looked up at him, and smiled a crooked smile, provoking in him the memory of a cat that always looked just so before it sat on his lap and trod its claws into his groin.

“Is it riches we’re talking about, Martin Sure . . . sword? Gold treasure and the like? Not slaves, I trust? We don’t hold with slaving on the Sea-Cat, no matter what our brothers of the Syndical Sea may care for.”

“Not slaves, Captain,” said Hereward. “But treasure of all kinds. More gold and silver than you’ve ever seen. More than anyone has ever seen.”

Fury’s smile broadened for a moment. She slid a foot forward like a dancer, moved to Hereward’s side and linked her arm through his, neatly pinning his sword-arm.

“Do tell, Martin,” she said. “Is it to be an assault on the Ingmal Convoy? A cutting-out venture in Hryken Bay?”

Her crew laughed as she spoke, and Hereward felt the mood change again. Fury was mocking him, for it would take a vast fleet of pirates to carry an assault on the fabulous biennial convoy from the Ingmal saffron fields, and Hryken Bay was dominated by the guns of the justly famous Diamond Fort and its red-hot shot.

“I do not bring you dreams and fancies, Captain Fury,” said Hereward quietly. “What I offer is a prize greater than even a galleon of the Ingmal.”

“What then?” asked Fury. She gestured at the sky, where a small turquoise disc was still visible near the horizon, though it was faded by the sun. “You’ll bring the blue moon down for us to plunder?”

“I offer a way through the Secret Channels and the Sea Gate of the Scholar-Pirates of Sarsköe,” said Hereward, speaking louder with each word, as the pirates began to shout, most in angry disbelief, but some in excited greed.

Fury’s hand tightened on Hereward’s arm, but she did not speak immediately. Slowly, as her silence was noted, her crew grew quiet, such was her power over them. Hereward knew very few others who had such presence, and he had known many kings and princes, queens and high priestesses. Not for the first time, he felt a stab of doubt about their plan, or more accurately Fitz’s plan. Fury was no cat’s-paw, to be lightly used by others.

“What is this way?” asked Fury, when her crew was silent, the only sound the lap of the waves against the hull, the creak of the rigging, and to Hereward at least, the pounding of his own heart.

“I have a dark rutter for the channels,” he said. “Farolio here, is a gifted navigator. He will take the star sights.”

“So the Secret Channels may be traveled,” said Fury. “If the rutter is true.”

“It is true, madam,” piped up Fitz, pitching his voice higher than usual. He sounded childlike, and harmless. “We have journeyed to the foot of the Sea Gate and returned, this past month.”

Fury glanced down at the puppet, who met her gaze with his unblinking, blue-painted eyes, the sheen of the sorcerous varnish upon them bright. She met the puppet’s gaze for several seconds, her eyes narrowing once more, in a fashion reminiscent of a cat that sees something it is not sure whether to flee or fight. Then she slowly looked back at Hereward.

“And the Sea Gate? It matters not to pass t

he channels if the gate is shut against us.”

“The Sea Gate is not what it once was,” said Hereward. “If pressure is brought against the correct place, then it will fall.”

“Pressure?” asked Fury, and the veriest tip of her tongue thrust out between her lips.

“I am a Master Gunner,” said Hereward. “In the chest aboard out skiff is a mortar shell of particular construction—and I believe that not a week past you captured a Harker-built bomb vessel, and have yet to dispose of it.”

He did not mention that this ship had been purchased specifically for his command, and its capture had seriously complicated their initial plan.

“You are well-informed,” said Fury. “I do have such a craft, hidden in a cove beyond the strand. I have my crew, none better in all this sea. You have a rutter, a navigator, a bomb, and the art to bring the Sea Gate down. Shall we say two-thirds to we Sea-Cats and one-third to you and your puppet?”

“Done,” said Hereward.

“Yes,” said Fitz.

Fury unlinked her arm from Hereward’s, held up her open hand and licked her palm most daintily, before offering it to him. Hereward paused, then spat mostly air on his own palm, and they shook upon the bargain.

Fitz held up his hand, as flexible as any human’s, though it was dark brown and grained like wood, and licked his palm with a long blue-stippled tongue that was pierced with a silver stud. Fury slapped more than shook Fitz’s hand, and she did not look at the puppet.

“Jabez!” instructed Fury, and her great hulking right-hand man was next to shake on the bargain, his grip surprisingly light and deft, and his eyes warm with humour, a small smile on his battered face. Whether it was for the prospect of treasure or some secret amusement, Hereward could not tell, and Jabez did not smile for Fitz. After Jabez came the rest of the crew, spitting and shaking till the bargain was sealed with all aboard. Like every ship of the brotherhood, the Sea-Cats were in theory a free company, and decisions made by all.

The Ragwitch

The Ragwitch Newt's Emerald

Newt's Emerald Grim Tuesday

Grim Tuesday Sabriel

Sabriel Mister Monday

Mister Monday The Missing

The Missing The Fall

The Fall A Confusion of Princes

A Confusion of Princes Troubletwisters

Troubletwisters Lirael

Lirael Lord Sunday

Lord Sunday Clariel

Clariel Drowned Wednesday

Drowned Wednesday Shade's Children

Shade's Children The Violet Keystone

The Violet Keystone Abhorsen

Abhorsen The Monster

The Monster The Creature in the Case

The Creature in the Case To Hold the Bridge

To Hold the Bridge Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar

Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Above the Veil

Above the Veil Aenir

Aenir Mystery of the Golden Card

Mystery of the Golden Card Superior Saturday

Superior Saturday Sir Thursday

Sir Thursday Castle

Castle Lady Friday

Lady Friday Into Battle

Into Battle Dislocation Space

Dislocation Space Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1)

Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1) Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1

Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1 The Left-Handed Booksellers of London

The Left-Handed Booksellers of London Novel - A Confusion of Princes

Novel - A Confusion of Princes One Beastly Beast

One Beastly Beast A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3

A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3 Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2

Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2 Have Sword, Will Travel

Have Sword, Will Travel Fire Above, Fire Below

Fire Above, Fire Below Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case

Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case The Monster (Troubletwisters)

The Monster (Troubletwisters) Across the Wall

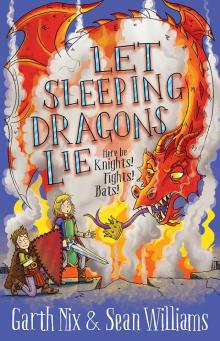

Across the Wall Let Sleeping Dragons Lie

Let Sleeping Dragons Lie![[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/abhorsen_03a_-_across_the_wall_preview.jpg) [Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall

[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall