The Ragwitch Read online

Page 10

“What else did she talk about?” asked Paul.

“Mice and sparrows,” replied Quigin. “But at least I managed to find out where they hold the Wind Moot—and get us invited there.”

“But what is the Wind Moot?” asked Paul.

“It’s a sort of meeting place for birds,” replied Quigin. “I think I can remember how Cagael described it, from The Book of Beasts, ‘High above certain mountains, where the currents of air run both cold and warm, to climb or fall through the clouds, the Birds of the Claw travel the way from East to West, and under Sun, or Light of Moon, the Wind Moot meets…’”

“The Birds of the Claw?”

“Oh, falcons, hawks, eagles,” explained Quigin. “Some of the larger owls, if the Moot is under moonlight. Sometimes other birds are called, ravens, swifts and suchlike. But it’s mostly for the hunters.”

“What do they do there?” asked Paul, thinking of a great cloud of birds, circling around, high in the air, for no apparent reason.

“They talk,” replied Quigin. “Or so I’ve been told. I’ve never been to one myself.”

“Oh,” said Paul, looking at the hawk’s cruel, curved beak, and remembering the giant crow that had attacked him on the midden so many days ago and a world away. “How big do these birds get? I mean…will it be safe?”

“I don’t know,” said Quigin cheerfully. “But it’s bound to be interesting!”

The hawk seemed to agree with Quigin, because it whistled briefly, and flew up, circling the basket before slowly flying off towards the setting sun. It flew slowly, and circled back several times—obviously waiting to guide them.

Quigin whistled again, and the hawk started climbing, up towards the first of the evening stars. The Friend of Beasts watched the bird’s effortless flight, and then addressed the balloon above, making some ritual gestures with his fingers and hands.

Paul watched, entranced, as the shadowy figures inside the gas-bag swelled and assumed a slightly orange hue. The balloon rose steadily in silence, following the hawk up into the night sky.

“I think I’ve finally got this balloon sorted out,” said Quigin, happily. “Look, there’s another hawk—and there, some sort of eagle…”

Julia screamed as she joined the Ragwitch’s senses, a long, inward cry of pain. Normally, it just felt unnatural and somehow unclean, but this time, pain lanced through her and she could see only blurred, cloudy visions through the Ragwitch’s eyes.

Slowly, the pain eased and the mist cleared from her sight. Julia felt the now familiar bloated limbs and dulled senses of the Ragwitch, and then Her thoughts burst into her mind, cold and biting.

“Pain, Julia? But it is not I that cause you pain. I am not unkind to those that serve me well. As you have begun to do.”

Julia didn’t answer, letting the dull ache in her head fade away, so she could see properly. Dimly, she felt that the Ragwitch was pleased with her, a prospect that was terrifying. What could she have done that helped the Ragwitch?

Gradually, Julia’s sight cleared, and she saw that they stood upon a road, a thin, gravelled road, bordered on each side by lightly wooded fields that looked as if they might once have been open farmland. Ahead, the road wound up through a clear expanse of short, greyish bushes towards a great cleft in the hills beyond, a jagged gorge of off-white rock, dripping with greenish water.

The Ragwitch gazed towards the gorge, and so, of course, did Julia. But they could see only a little way into the dark passage, where the road dipped down past the white stone bluffs.

Only then did Julia realize it was night. Instead of the sun, a huge three-quarter moon hung low over the gorge—almost directly above it, but not quite in the right place to light up the depths below.

The Ragwitch moved Her head, straw spilling from the rounded folds at Her neck, and Julia saw that She stood on the road alone—but under the shadow of the trees, the Gwarulch lurked, and the Angarling stood as silent as the stillest trees. And there was another shape, black in the blackest shadow. The Ragwitch beckoned, and it stepped forward into the moonlight. Julia recognized Oroch, and hoped this was not another of his failures—she didn’t want to even begin to see what lay under those tar-black bandages.

“Oroch,” hissed the Ragwitch. “Have the Gwarulch returned?”

“No, Mistress,” said Oroch, squirming. “First two and twenty, and then four and forty went down to the Steps. But none have returned. And the Meepers have lost fifteen of their number, and now they will not fly.”

“Order them aloft, or twice that number will burn!” spat the Ragwitch, menacingly. She leaned over Oroch, and he stepped back, slipping on the thick gravel.

“That which holds the Namyr Steps is not for them,” continued the Ragwitch, spittle dripping from Her red-painted lips. “I have been attacked, Oroch—they have dared to attack Me! And now, they will answer for it!”

Oroch nodded fearfully, hesitantly squeaking out, “But what is it, oh Mistress? Is it…dangerous?”

Julia felt a strange amusement ripple through the Ragwitch, before She answered. “It has already cast a spell against Me, Oroch. But it is only one, and not of the First Rank. And what of spells, when all that strike Me first strike the child?”

As She spoke, Julia felt the Ragwitch’s amusement increase, and then, She was cackling aloud, while Oroch giggled, and the Gwarulch in the trees snorted their agreement at whatever She enjoyed.

And inside, She whispered to Julia under the cackling, “And so, my rescuer, you are curse and spell-trap, chantward and shield. And those who may strive against Me, will wound and pierce a child. And you will feel the pain of every spell against Me. You will feel the pain…”

The Ragwitch stopped cackling, and slowly began to move down towards the gorge called the Namyr Steps. Behind Her, Oroch capered, still giggling; the Angarling lumbered after Her, and the Gwarulch streamed through the trees on either side, pausing only to rend any small beast or nocturnal bird that fled too late. Above, Meepers flew as far back as they dared, fearing to go on, but obedient to their Mistress, who was their greatest fear.

“She’s coming,” said Thruan, holding out his thumbs which were twitching, seemingly without his control. “We had best leave while we still can.”

The woman who had come up beside him shook her head. “That’s what I came up to tell you—we can’t get out. There is a Black Veil across the last of the Steps. Lyalbec touched it, and it withered his arm.” She grimaced, showing an old white scar that ran from the corner of her mouth to one of the face-bars of her helmet. “Fortunately, Lyalbec is left-handed. He can still use a sword. If that will do us any good…?”

She phrased the last part as a question, and Thruan hesitated a second before answering, black eyebrows meeting above his wide nose, a frown of puzzlement rather than deep thought.

“I think swords and arrows will play a little part, before the night is done. But only a little, and it will not be enough for us. I am now sure that it is the Ragwitch we are facing—once North-Queen and Witch—for there is a great and evil power there. And yet…my first spell against Her was not countered, nor exactly turned…”

A whistle higher up the gorge interrupted him, and the woman picked up her bow, and loosened the basket-hilted sword at her side.

“I’ll go up now,” she said. “If whatever comes down the Steps is flesh and blood, we’ll stop it. If not—well, at least Aenle got through before the Black Veil formed. Caer Calbore will not go unwarned.”

“My thanks, Captain,” said Master Thruan. “I will do what I can.”

She nodded and said, “It is well we met you going north. If one must fight, and on a stricken field, it is easier to bear in company. Farewell.”

Thruan watched her climbing up the limestone steps that gave the Namyr gorge its name. On either side of the passage, men and women rose up from their brief rest, buckling on breastplates over buff coats, or strapping on their helmets with the three-barred visors. Higher up, Gwarulch cor

pses grinned, either feathered with arrows or slain by Thruan’s Magic, more chilling to them than the sharpest steel.

Thruan watched, counting, till all thirty of the survivors were spread out below the topmost step, readying their bows, laying out blue-feathered arrows for a last stand. Then he looked to the pool of water on the seventy-seventh step and bent his mind to the southeast. He hoped to have one last look at his balloon, and perhaps learn more of the significance of this…Paul.

Slowly, the water began to cloud, and Thruan saw a field of stars behind some scudding wisps of cloud. Birds of prey wheeled across the sky, hundreds of them, circling a yellow-lozenged balloon. Two figures stood within the basket: one, Cagael’s apprentice, Quigin, and the other, presumably, Paul…

Another whistle came from above, and the vision faded. Thruan turned from the pool, and began to climb the steps, readying his scant powers. Already bowstrings twanged above, and Gwarulch screams echoed in the gorge. But the Gwarulch were not alone, and Thruan’s thumbs twitched in dire warning as the Ragwitch reached the topmost step, death and darkness rolling like a cloud before Her.

9

The Wind Moot/Glazed-Folk

THIS IS FANTASTIC!” shouted Paul—he had to shout, over the shrill cries and whistles of all the birds that surrounded the balloon. Everywhere he looked, there were fierce-eyed hawks and falcons, wheeling and screeching like a flock of some strange, sharp-taloned seagulls.

The balloon, like the birds, was riding on a warm updraft. Looking up, it seemed to Paul that he was falling, falling towards the brilliant, three-quarter moon, and the clear, steady twinkling of the stars, riding in their strange constellations with even stranger names.

Paul had never thought that so many birds of prey would gather in such a small space—from tiniest hawk to the largest eagle, spiralling upwards to some airy and mystical location.

Quigin loved it, of course, Paul had been unable to get him to listen to anything—he was too intent on the roar of bird-calls. Every now and then, he nodded his head, and mumbled, “Of course…but I knew that…well, at least a bit…” Then he would screech in return, and even more birds would gather around the balloon. One old eagle (it had a bald head) even went so far as to hitch a ride, gripping the rim of the basket with talons the size of Paul’s fingers. It watched him with an unblinking eye, then turned its attention back to the sky, either not noticing or ignoring the terrified Leasel, who lurked in the darkest corner of the basket, surrounded by the solid leather bags.

Suddenly, the balloon lurched, falling off the updraft. The birds stopped climbing too, and fell silent, until the only noise was the rush of air from thousands of wings, and the rasp of Paul’s and Quigin’s breath, hot and steaming in the high, cold air.

Paul sneaked a glance over the side of the basket, shivering as he realized how high up they were. Aillghill mountain was just a tiny white speck below, brilliant in the moonlight. The world seemed to curve away forever on every side, and for the first time in his life Paul knew the world was really round.

Still looking down, Paul felt his head become light and somehow disconnected, and for an instant, he felt like jumping off, to float above the enormous world below. But the basket lurched again, and he looked back up, grabbed the railing, and took a deep breath to regain normality.

“High up, aren’t we?” said Quigin unnecessarily. “I’ve never been up this high before. Or at night. And the birds…I’ve learnt more in the last hour than in the last three months…why, Master Cagael will be…”

“Quigin,” interrupted Paul, in a small, rather shaky voice. “Do you think that might be the Master of Air?”

Quigin stopped in mid-sentence, and looked where Paul was pointing with a hand that seemed to shiver with something more than cold. Paul was pointing towards the moon, and at first Quigin couldn’t see anything. Then something passed between him and the moonlight. Something swift and dark that blotted out most of the moon’s three-quarter disc.

Quigin nodded in answer to Paul’s question, but Paul wasn’t watching. He was thinking, if that is the Master of Air, what am I supposed to do? And he remembered Tanboule’s words, a dim and hardly remembered warning: “…and indeed, they may put troubles in your way…”

The dark shape grew closer and closer, still following a line directly in front of the moon. Squinting against the light, Paul could vaguely make out the thing’s shape, a shape that became more clearly defined as it drew even closer with each beat of its vast wings.

The birds started calling again as it approached—softly, in time to the beat of the larger eagle’s wings. It was obviously a most respectful welcome.

Then the dark shape was level with them. It was no longer blocking out the moonlight, but shining in it: an enormous eagle, with sky-blue feathers that ruffled in its wake; beak and talons as silver as the moon, and eyes as black as coal.

Paul stared at it, thinking its body alone was bigger than his school bus, and the wings were longer than his uncle’s glider. His throat dried up, and he felt a pulse of fear, much like when Ornware had stood above him with his bloody, rune-carved spear. Then he had lain in the shadow of antlers, but now he faced the far greater shadow of the eagle’s wings and an awesome, more elemental power.

The great bird circled the basket, watching, while Paul opened and shut his mouth several times, and Quigin stood gaping. Then, Paul caught a glint in the eagle’s eye, a spark of silent laughter, and he suddenly felt everything would be all right.

“Hello!” shouted Paul across the winds. The eagle checked its motion, and began to hover in place, with a constant beat of wings. It seemed to consider Paul for a moment, and then…dissolved. Slowly, each blue feather became transparent, as though the color were being drained from a stained-glass window, leaving only tracery behind. And then even the vague outline of an eagle vanished, pieces tumbling towards the balloon like chaff in a breeze.

“Slugweed,” whispered Quigin, in a tone of vast amazement. “Wort and Sheepsbane.”

Paul just stared at the empty space where the eagle had been. Already, the last fading feathers were gone, but in their place, Paul could just see something taking shape, like mist rising from the ground.

“What should I do?” whispered Paul to Quigin, as the shape opposite them began taking on a more substantial form. It was starting to look like an enormous human head, at least twenty meters high, with flowing hair and a beard that trailed below, blowing back into the space normally occupied by a neck.

“You could say hello again,” whispered Quigin. “I mean, when you said it last time, the eagle fell apart…”

“But I want its help,” Paul whispered back, controlling a strong urge to join Leasel in the dark corner, and close his eyes. The head was getting features now, and they didn’t look particularly nice.

“I could try hawk-whistling at it,” said Quigin doubtfully. He looked around at the column of birds, which were silent again, after their greeting cries. They seemed undisturbed by the appearance of the head.

“I suppose you…” began Paul, when the head suddenly moved. Its nose (which had only just appeared) began to twitch, and the mouth began to yaw open, revealing a cavernous, mist-walled void, complete with tongue and tonsils.

“It’s going to sneeze!” shouted Paul, ducking down into the basket, with Quigin close behind. Great gusts of wind sucked into the mouth, the ropes and wrappings of the basket whipping about in the sudden vacuum. Paul and Quigin shut their eyes, held onto the basket, and waited for the mammoth explosion of a twenty-meter-high head’s sneeze. But at the last moment, it held the sneeze in, and gave a gentle sigh instead.

The air was suddenly calm, and the basket still. A great voice boomed out with a gentle rush of warm air:

“I am the North Wind and the South Wind, the Wind from West and East. I am the still air, the fiercest zephyr, the dusty wind from a tomb. I am the bearer of birds, and the carrier of clouds. I am the Master of Air.”

Paul gulped twi

ce, and slowly stood up, unconsciously bending his knees so he didn’t have to show anything but his eyes and mouth above the rim of the basket.

“Hi!” he shouted nervously. “I’m Paul…Your…um…Mastership. Tanboule sent me to you…at least he said…”

“What did he say?” boomed the Master of Air, or at least his physical manifestation, the Head. Paul noticed it had no teeth—but it had the yellow, predatory eyes of an eagle.

“He said you could help me,” shouted Paul, wishing he knew what to say. “He said that you could help me get Julia back from the Ragwitch.”

The Head’s eyes widened at this, the lids pulling back and then closing again, as the Master of Air narrowed his eyes, and considered the tiny speck of a boy before him.

“Why should I help you?” asked the Head, in a less booming, and slower tone.

Paul bit his lip, and looked at Quigin for advice. But Quigin just smiled, and shrugged. Not for the first time, Paul wished Aleyne was there to help him. Or Julia…but then, if Julia was here…he wouldn’t be…

“Well?” said the Head, in the slightly impatient tone of a teacher asking a very easy question. “Well?”

“Well, just…” began Paul, trying to think of a reason the Air itself would help him. But what could possibly influence the Master of Air?

“You should help,” he continued, “you should help…just…because!”

Even as he shouted “because!,” Paul felt a terrible sense of failure. I’ve come all this way, he thought, through all sorts of terrible things, and when I get the first chance to really help Julia, I blow it! “Because”—what sort of answer is that?

“Because?” rumbled the Head, gusts of warm air rolling out with every syllable. The gusts became stronger, and the Head repeated Paul’s answer several times, each time stretching the word over several breaths, till it was a series of unrecognizable coughs.

Then Paul realized the Master of Air was laughing.

The Ragwitch

The Ragwitch Newt's Emerald

Newt's Emerald Grim Tuesday

Grim Tuesday Sabriel

Sabriel Mister Monday

Mister Monday The Missing

The Missing The Fall

The Fall A Confusion of Princes

A Confusion of Princes Troubletwisters

Troubletwisters Lirael

Lirael Lord Sunday

Lord Sunday Clariel

Clariel Drowned Wednesday

Drowned Wednesday Shade's Children

Shade's Children The Violet Keystone

The Violet Keystone Abhorsen

Abhorsen The Monster

The Monster The Creature in the Case

The Creature in the Case To Hold the Bridge

To Hold the Bridge Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar

Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Above the Veil

Above the Veil Aenir

Aenir Mystery of the Golden Card

Mystery of the Golden Card Superior Saturday

Superior Saturday Sir Thursday

Sir Thursday Castle

Castle Lady Friday

Lady Friday Into Battle

Into Battle Dislocation Space

Dislocation Space Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1)

Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1) Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1

Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1 The Left-Handed Booksellers of London

The Left-Handed Booksellers of London Novel - A Confusion of Princes

Novel - A Confusion of Princes One Beastly Beast

One Beastly Beast A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3

A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3 Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2

Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2 Have Sword, Will Travel

Have Sword, Will Travel Fire Above, Fire Below

Fire Above, Fire Below Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case

Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case The Monster (Troubletwisters)

The Monster (Troubletwisters) Across the Wall

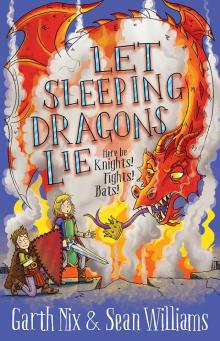

Across the Wall Let Sleeping Dragons Lie

Let Sleeping Dragons Lie![[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/abhorsen_03a_-_across_the_wall_preview.jpg) [Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall

[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall