Have Sword, Will Travel Read online

Page 19

“I didn’t take in a lot of water and need my back slapped like a baby,” she griped.

“You’re lucky,” said Odo. He was watching the water, and suddenly waded out to grab a long beam of good timber, once part of the dam. It was a little charred but sound.

“I am lucky,” agreed Eleanor. She thought about that for a moment, then drew Runnel half an inch out of her scabbard. “Hey, Runnel! You hear that? I fought three brigands and won, and I survived the dam breaking and the flood. You can’t be cursed at all.”

“Hmmm,” said Runnel, unconvinced. “Perhaps it is a slow curse. Or delayed somehow.”

“And there was no dragon,” pointed out Odo as he dragged the beam out of the water and waded in to collect another, all raw material for the raft he was already designing in his mind. “That’s lucky too.”

“Perhaps,” said Runnel. There was a note of regret in her voice.

“Hey, help me with this,” said Odo. “Get that small one there.”

Eleanor nodded, but paused to look down at her sword.

“There is no curse, Runnel,” she repeated. “You were unlucky with your knights, that’s all. There was never any curse.”

Runnel did not reply, or if she did it was so quietly that whatever she said was lost as Eleanor splashed into the water and grabbed a piece of floating wood from Odo’s firm grasp.

* * *

By early morning, the full devastation caused by the destruction of the dam was clear to see. The raging floodwaters had ebbed all the way back to the river channel, which now ran at a spate to the top of the banks, but did not overflow them. For half a league on either side, all that was visible was mud, toppled trees, and debris.

There was also a massive cloud of black smoke still hanging over the gorge. A reddish reflection under the cloud suggested that some part of the dam still burned.

“The mixture will burn underwater,” said Old Ryce. “Mayhap there’s some left in the cylinder …”

The ancient artificer had proved to be very useful in making their raft. He’d built ships, he told them, and all kinds of terrible engines for use in war. Captain Vileheart had hired him in far-off Axim, across the sea, but had soon made him a slave. He didn’t want to talk about that, though, and every time they said “Vileheart” or “Sir Saskia” he would stop talking and begin to shake.

The first and most important piece of good advice Old Ryce had given them was to start making the raft on the riverbank, even when it was still knee-deep in floodwater. This meant they only had to push it a few feet into the water, instead of trying to drag it across a broad expanse of very sticky mud. Which probably wouldn’t have worked, because it was a heavy vessel, mostly made of beams from the dam held together with rope, nails, bolts, and wire, all scrounged from the bandits’ guard camp and the ruins of Hellmere. The scrounging had taken most of the morning, once the sun came up.

“You ready?” Odo asked Eleanor. She and Old Ryce were already on the raft. Its front quarter was in the river, the water rushing at it, trying to drag it away. One good shove from Odo and they’d be off. Without him, if he couldn’t jump on board fast enough. “It’s going to go very fast.”

Eleanor took a tighter grip on the rope they’d lashed across the raft for passenger support and checked to make sure their armor and the two swords were secure, tied down with another rope. Old Ryce changed his handhold and gave her an uncertain, largely toothless grin.

Odo pushed. The raft moved a few inches in the mud then stuck fast. He got down lower and heaved again, really getting his full strength behind it. His left shoulder, the one hurt by Sir Saskia, twinged. He grimaced, but didn’t stop pushing.

Inch by inch, the raft moved out into the river. Water foamed up all along one side, splashing over Eleanor and Old Ryce … and then suddenly the raft spun sideways and was away!

Odo, caught by surprise, hurled himself forward and just managed to grab hold of the stern rope and pull himself half onto the raft even as it rocketed down the river, wallowing and bucking with the force of the flood.

“Climb up!” shouted Eleanor. The raft was rocking so wildly and going so fast she didn’t dare let go and move back to help Odo.

“That’s what I’m doing!” Odo shouted back. “It’s harder than it looks!”

He got his right knee up and then the whole leg, and with a huge effort managed to roll completely onto the raft. But he knew he couldn’t rest there. The raft was spinning and crashing into the riverbank every ten or twelve paces, and at this rate would be shaken to pieces long before they got to Lenburh.

Tucking his legs under the stern rope, he sat up and reached over to pull out one of the long poles from where it had been secured. Holding it with both hands, he used it to fend the raft off from the riverbank just as it went in for another collision.

Eleanor, up at the bow, was already doing likewise. She didn’t have Odo’s weight, but she was fiercely determined, which counted for a great deal.

Old Ryce cackled and threw his hands in the air for a second, almost resulting in him going overboard.

“It ain’t what I’d call shipshape and Jyllen fashion,” he announced, grabbing hold of the rope again. “But it works.”

“We’re going so fast,” said Eleanor, relishing the feel of chill air on her face. The sensation made up for being hungry. They hadn’t gone back for their packs, high above the gorge, and though they’d taken the bandits’ food and drink, that had all been consumed at breakfast. “If this keeps up we might be at Lenburh by tomorrow morning!”

“The flood will slow as we get farther along,” said Odo. But he grinned and said, “It will certainly be a lot faster than walking. We’ll beat Sir Saskia to Lenburh for sure.”

“Will we be able to stop the raft?” asked Eleanor as they pushed hard to avoid hitting the riverbank again and were suddenly carried out towards the middle, where the river flowed even faster.

“I, uh, hope so,” said Odo, realizing only then the significance of her question. He had been so focused on making the raft and getting it going he hadn’t once thought about how they would stop.

Poling ashore proved to be much harder than either of them expected. They didn’t even try for the first few hours, since it was obvious they would fail, the river foaming and roaring and carrying them along so quickly. Later in the afternoon, the flood did seem to ease a bit, and they tried to pole for the riverbank several times, but still without any success.

“We’ll be carried past Lenburh at this rate,” said Eleanor. “Look, that’s Hryding up ahead!”

“Pole!” shouted Odo. “Pole hard!”

They pushed with all their strength. It was useless. Although the raft came close to the riverbank, it spun as it did so and was quickly carried back into the main flow despite everything Odo and Eleanor could do. To make matters worse, the raft was also slowly beginning to come apart, unable to withstand the many knocks and collisions with debris and the riverbanks.

“Eels,” said Biter. “I feel I may soon be joining the eels again.”

“No you won’t,” said Odo, but not with complete conviction. Inwardly he was afraid the sword might be right. “The flood will ease, I’m sure of it.”

He knew this was true. Eventually. But they might be well past Lenburh before that happened, if the raft lasted that long. Visions filled his mind of trudging back to Lenburh from the south, only to find it burning, Sir Saskia and her troops looting and pillaging and killing …

“The jetty,” said Eleanor suddenly. “The jetty at Anfyltarn.”

Odo’s waking nightmare disappeared.

“Yes!” he said. “We should be able to steer into that at least!”

Eleanor was calculating.

“If the river keeps up this speed, I reckon we’ll arrive about dusk.”

“We might be able to get a horse from the smiths,” said Odo.

“How far do you think Sir Saskia will have got?” asked Eleanor.

“I don’t kno

w,” said Odo. “We’d better keep a good lookout.”

“The bandits you didn’t kill would have reached her by now,” said Runnel. “She will be forewarned.”

“They won’t expect us,” said Odo. “At least not on the river.”

“She sounds clever,” said Runnel. “Perhaps clever enough to expect the unexpected. Remember what I said about people not guarding the unexpected ways? That doesn’t apply to the really smart commanders.”

With those unsettling words sinking deep into their thoughts, provoking a whole cavalcade of new worries, Odo and Eleanor resumed trying to pole the raft away from major collisions with debris, not get washed overboard themselves, and keep an eye out for any of Sir Saskia’s soldiers on the riverbank.

They saw few people at all, probably because everyone who lived nearby had taken to higher ground in case of more flooding. Where everyone had been distraught about the lack of water in the river, now they were frightened of too much water. Particularly as the flood had been announced by a deafening thunderclap, a gout of fire that reached to the sky, and a vast black cloud that was only beginning to blow away.

One fellow who was wading about in a flooded pasture near the river shouted something as the raft passed, but they could only hear one word clearly. That was “Dragon!”

“I suppose people think Quenwulf dried up the river, and Quenwulf flooded it too,” said Odo.

“They’ll know the truth soon enough,” said Eleanor. “No dragon needed. Just a black-hearted drassock and her minions.”

“We’ll sort out Sir Saskia,” said Odo. “Sir Halfdan can send word to the King’s Wardens, and his nephews’ manors are only a day’s march south. There are three of them and they have squires and armed retainers. And with warning, everyone in the village can fight.”

It was a surprise attack he feared. Without time to prepare and gather at Sir Halfdan’s manor house, the villagers wouldn’t stand a chance. It would be terrible — beyond terrible — if Odo and Eleanor succeeded in their quest to free the river only to come home and find out there was no one left to enjoy a normal life returned.

Odo brooded on this as he pushed the raft away from the vast, tangled root-section of a fallen tree. A normal life. Did he really want to give up Biter and stop being a knight? Eleanor didn’t need the sword now, since she had Runnel. Doubtless she would go on questing and become a knight herself. But what would Odo do?

Would he continue to be Sir Odo, or return to being Odo, the miller’s seventh child? He’d been so sure when he left that he didn’t want to be a knight. Now … he was almost sure he didn’t want to be a miller’s son again.

“The jetty!” cried Eleanor from the front of the raft.

They’d made even faster time than she had thought. The sun was only just beginning to set, and there, only a few hundred paces ahead, was the Anfyltarn jetty. It looked totally different now, with the water right up to the planks, and even over them in a few places, as if it were an almost-submerged bridge jutting out into the floodwaters.

“We’re going to hit it!” she exclaimed.

Eleanor was relieved because if they didn’t, the river was going to keep taking them along, and neither of them could find bottom with their poles to push against.

The raft hit hard, loosening more of its timbers. For a moment it seemed as if it might swing away and around the end of the jetty, but Odo leaned out and grabbed one of the posts and held the vessel in place. Old Ryce jumped off as best he could, considering his knees, and tied a rope to another post. Eleanor made a loop with her rope and caught a third, swiftly tying a knot.

“Quick!” said Eleanor, reaching across to grab Runnel in her scabbard. “It’s coming apart!”

The battered raft was disintegrating under Odo’s weight. He threw Biter in his scabbard onto the jetty, and then their armor, and jumped himself only a few seconds before the raft broke into pieces and the pieces swirled away.

The jetty didn’t feel all that solid under their feet either. It was swaying and groaning, the river tearing at it like a wild beast. Odo, Eleanor, and Old Ryce snatched up their gear and ran for the riverbank, splashing through mud until they found the river road, which had not been reached by the floodwaters.

Only then did Eleanor’s gaze rise to where she knew Anfyltarn was located, up the hill beyond the forest. There she saw columns of smoke, as there had been on their previous visit.

But there was a lot more smoke now, great billows of black-and-white smoke rising to the sky. Far more than could come from the forges of the smithy alone.

“Odo,” she said. “I think Sir Saskia took a detour on the way to Lenburh.”

“Why would she do that?”

“Because I told Mannix about your armor. She’ll want to replace anything lost in the flood … and to make sure no one else can do the same.”

It made a horrible kind of sense, given what they now knew about the villain. Help herself without caring about anyone else.

They put their armor on as quickly as they could, and with swords in hand began to climb up the hill. Old Ryce stayed behind. He’d started to follow, but only went a few steps before he had to stop, quivering and shaking at the prospect of being recaptured by Captain Saskia Vileheart.

Odo told him to hide and await their return.

“We definitely will return,” Eleanor told him. “So stop your whimpering.”

“Old Ryce doesn’t doubt it,” he said, clutching at their hands. “He doesn’t dare …”

They followed the same track as before, when they’d chased Toland. It seemed as if that had happened months before, Odo thought as they carefully moved to the fringe of trees. So much had happened since then, in only a short time. Now, as then, there was no possibility of turning back. Duty called him forward.

Through the forest they heard shouts and cries and the clash of battle up ahead. Smoke was drifting through the trees. Hurrying to the edge of the cleared area, they saw that part of the palisade was on fire and soldiers were massed in front of it, ready to charge through when enough of it was burned away. But there were plenty of defenders behind other parts of the palisade, firing bows and crossbows and even throwing rocks, and several bucket chains of villagers were bringing water from the central well to throw on the burning timbers.

The besiegers were Sir Saskia’s troops, as Eleanor and Odo had suspected. Sir Saskia herself was only a hundred paces away, standing some distance to the rear of her troops, safely out of bowshot. Mannix stood by her side holding a trumpet, but there were no others close by.

“Charge the miscreant knight now!” cried Biter, jabbing himself forward, Odo holding him back.

“Wait,” warned Runnel. “Coolness in battle is essential. Assess the enemy, the lay of the land, and the likelihood of the outcome.”

“If we can defeat Sir Saskia, the others will run,” Eleanor strategized. “There’s just her and Mannix. We can do it.”

“She defeated me easily before,” Odo pointed out.

“Well, she hasn’t fought me yet,” said Eleanor, hoping she sounded as brave as she wanted to sound. There wasn’t time for second thoughts. A section of the palisade fell in with a mighty roar and a huge billow of smoke. “Look, they can’t hold the wall for long, and once the enemy is inside, the smiths will be outnumbered.”

Odo nodded. He was staring at the battle, frozen in indecision. Ordinary people were dying there, being wounded, doing their best to defend themselves against coldhearted killers. Smiths and apprentices, villagers who had woken up that morning without fear, going about their normal business, only to be attacked for no reason save greed and viciousness.

All those ordinary people who would be killed unless someone helped them.

“I’ll take Mannix,” said Odo calmly, bumping a fist against his chest as though clearing an obstruction. “No mercy for either of them.”

Eleanor bared her teeth, raising Runnel high above her head, the ruby in the pommel catching the sunlight in su

ch a way it bathed the whole blade in a bright red light. Then she broke into a run.

Sir Saskia turned as Eleanor closed the last few paces. Amidst the noise of battle she hadn’t heard the girl’s approach until she was almost upon her, and even then it was only well-trained combat senses that raised the alarm. She ducked under Runnel’s first, powerful swing and sprang away, drawing Ædroth. She managed this just in time to parry a series of blows, giving ground with each one.

Mannix had not been as fast as his knight. He managed to interpose the trumpet between Odo’s first two-handed downward blow, but the impact sent him sprawling to the ground. He lay there, weaponless, and held out his hands.

“Chivalry demands you allow me to stand and draw!” he shouted as Odo furiously raised Biter above him.

Neither sword nor knight hesitated. Biter came down point-first on Mannix’s shoulder, shearing through his armor as if it were no more than river mud. Mannix screamed and swore and clutched at the wound with his left hand, his right arm now useless.

“Chivalry is wasted on bandits,” said Biter with uncharacteristic acid. The emerald in his pommel flashed. “Come, Sir Odo. We must hold these others off the squire, who is showing uncommon valor.”

Odo looked around. He’d been totally caught up with attacking Mannix and was shocked to have won so easily. Eleanor and Sir Saskia were trading blows a dozen paces away, both dancing forward and back, swords flashing so fast he could barely see them.

Most of Sir Saskia’s troops were trying to force their way through the smoking breach in the palisade and into a wild melee with the best-armored smiths, who were fighting with massive hammers. But a group of six bandits had turned back and were coming towards Odo.

“Six!” muttered Odo under his breath. “With spears!”

“Dare I suggest a frontal assault —?”

Before Biter could finish the sentence, Odo charged at the enemy, screaming a wordless battle cry.

Eleanor saw Odo’s wild charge out of the corner of her eye, but could give it no thought. Every part of her being, mind, and muscle was focused on fighting Sir Saskia. Runnel was doing much of the work, but Eleanor had to anticipate what the sword wanted to do, and go with her, rather than against her, and for the first time she was really managing to do all of that at the same time.

The Ragwitch

The Ragwitch Newt's Emerald

Newt's Emerald Grim Tuesday

Grim Tuesday Sabriel

Sabriel Mister Monday

Mister Monday The Missing

The Missing The Fall

The Fall A Confusion of Princes

A Confusion of Princes Troubletwisters

Troubletwisters Lirael

Lirael Lord Sunday

Lord Sunday Clariel

Clariel Drowned Wednesday

Drowned Wednesday Shade's Children

Shade's Children The Violet Keystone

The Violet Keystone Abhorsen

Abhorsen The Monster

The Monster The Creature in the Case

The Creature in the Case To Hold the Bridge

To Hold the Bridge Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar

Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Above the Veil

Above the Veil Aenir

Aenir Mystery of the Golden Card

Mystery of the Golden Card Superior Saturday

Superior Saturday Sir Thursday

Sir Thursday Castle

Castle Lady Friday

Lady Friday Into Battle

Into Battle Dislocation Space

Dislocation Space Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1)

Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1) Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1

Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1 The Left-Handed Booksellers of London

The Left-Handed Booksellers of London Novel - A Confusion of Princes

Novel - A Confusion of Princes One Beastly Beast

One Beastly Beast A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3

A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3 Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2

Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2 Have Sword, Will Travel

Have Sword, Will Travel Fire Above, Fire Below

Fire Above, Fire Below Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case

Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case The Monster (Troubletwisters)

The Monster (Troubletwisters) Across the Wall

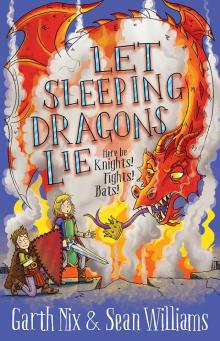

Across the Wall Let Sleeping Dragons Lie

Let Sleeping Dragons Lie![[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/abhorsen_03a_-_across_the_wall_preview.jpg) [Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall

[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall