Across the Wall Read online

Page 2

‘Isn’t that enough?’ asked Nick with a shudder. He remembered the newspaper stories from the last time Dorrance had been in the city, only a few weeks before. He’d hosted a picnic on Holyoak Hill for every apprentice in Corvere and supplied them with fatty roast beef, copious amounts of beer, and a particularly cheap and nasty red wine, with predictable results.

‘Dorrance’s eccentricities are all show,’ said Edward. ‘Misdirection. He is in fact the head of Department Thirteen. Dorrance Hall is the Department’s main research facility.’

‘But Department Thirteen is just a made-up thing, for the moving pictures. It doesn’t really exist . . . um . . . does it?’

‘Officially, no. In actuality, yes. Every state has need of spies. Department Thirteen trains and manages ours, and carries out various tasks ill-suited to the more regular branches of government. It is watched over quite carefully, I assure you.’

‘But what has that got to do with me?’

‘Department Thirteen observes all our neighbours very successfully, and has detailed files on everyone and everything important within those countries. With one notable exception. The Old Kingdom.’

‘I’m not going to spy on my friends!’

Edward sighed and looked out the window. The drive beyond the gatehouse curved through freshly mown fields, the hay already gathered into hillocks ready to be pitchforked into carts and taken to the stacks. Past the fields, the chimneys of a large country house peered above the fringe of old oaks that lined the drive.

‘I’m not going to be a spy, Uncle,’ repeated Nicholas.

‘I haven’t asked you to be one,’ said Edward as he looked back at his nephew. Nicholas’s face had paled, and he was clutching his chest. Whatever had happened to him in the Old Kingdom had left him in a very run-down state, and he was still recovering. Though the Ancelstierran doctors had found no external signs of significant injury, his X-rays had come out strangely fogged and all the medical reports said Nick was in the same sort of shape as a man who had suffered serious wounds in battle.

‘All I want you to do is to spend the weekend here with some of the Department’s technical people,’ continued Edward. ‘Answer their questions about your experiences in the Old Kingdom, that sort of thing. I doubt anything will come of it, and as you know, I strictly adhere to the wisdom of my predecessors, which is to leave the place alone. But that said, they haven’t exactly left us alone over the past twenty years. Dorrance has always had a bit of a bee in his bonnet about the Old Kingdom, greatly exacerbated by the . . . mmm . . . event at Forwin Mill. It is possible that he might discover something useful from talking to you. So if you answer his questions, you shall have your Perimeter pass on Monday morning. If you’re still set on going, that is.’

‘I’ll cross the Wall,’ said Nick forcefully. ‘One way or another.’

‘Then I suggest it be my way. You know, your father wanted to be a painter when he was your age. He had talent too, according to old Menree. But our parents wouldn’t hear of it. A grave error, I think. Not that he hasn’t been a useful politician, and a great help to me. But his heart is elsewhere, and it is not possible to achieve greatness without a whole heart.’

‘So all I have to do is answer questions?’

Edward sighed the sigh of an older and wiser man talking to a younger, inattentive, and impatient relative.

‘Well, you will have to appear a little bit at the party. Dinner and so forth. Croquet perhaps, or a row on the lake. Misdirection, as I said.’

Nicholas took Edward’s hand and shook it firmly.

‘You are a splendid uncle, Uncle.’

‘Good. I’m glad that’s settled,’ said Edward. He glanced out the window. They were past the oak trees now, gravel crunching beneath the wheels as the car rolled up the drive to the front steps of the six-columned entrance. ‘We’ll drop you off, then, and I’ll see you Monday.’

‘Aren’t you staying here? For the house party?’

‘Don’t be silly! I can’t abide house parties of any kind. I’m staying at the Golden Sheaf. Excellent hotel, not too far away. I often go there to get through some serious confidential reading. Place has got its own golf course, too. Thought I might go round tomorrow. Enjoy yourself!’

Nicholas hardly caught the last two words as his door was flung open and he was assisted out by Edward’s personal bodyguard. He blinked in the afternoon sunlight, no longer filtered through the smoked glass of the car’s windows. A few seconds later, his bags were deposited at his feet; then the Chief Minister’s cavalcade started up again and rolled down the drive as quickly as it had arrived, the Army trucks leaving considerable ruts in the gravel.

‘Mr Sayre?’

Nicholas looked around. A top hatted footman was picking up his bags, but it was another man who had spoken. A balding, burly individual in a dark-blue suit, his hair cut so short it was practically a monkish tonsure. Everything about him said policeman, either active or recently retired.

‘Yes, I’m Nicholas Sayre.’

‘Welcome to Dorrance Hall, sir. My name is Hedge—

’ Nicholas recoiled from the offered hand and nearly fell over the footman. Even as he regained his balance, he realized that the man had said Hodge and then followed it up with a second syllable.

Hodgeman. Not Hedge.

Hedge the necromancer was finally, completely, and utterly dead. Lirael and the Disreputable Dog had defeated him, and Hedge had gone beyond the Ninth Gate. He couldn’t come back. Nick knew he was safe from him, but that knowledge was purely intellectual. Deep inside him, the name of Hedge was linked irrevocably with an almost primal fear. ‘Sorry,’ gasped Nick. He straightened up and shook the man’s hand. ‘Ankle gave way on me. You were saying?’

‘Hodgeman is my name. I am an assistant to Mr Dorrance. The other guests do not arrive till later, so Mr. Dorrance thought you might like a tour of the grounds.’

‘Um, certainly,’ replied Nick. He fought back a sudden urge to look around to see who might be listening and, as he started up the steps, resisted the temptation to slink from shadow to shadow just like a spy in a moving picture.

‘The house was originally built in the time of the last Trouin-Durville Pretender, about four hundred years ago, but little of the original structure remains. Most of the current house was built by Mr Dorrance’s grandfather. The best feature is the library, which was the great hall of the old house. Shall we start there?’

‘Thank you,’ replied Nicholas. Mr Hodgeman’s turn as a tour guide was quite convincing. Nicholas wondered if the man had to do it often for casual visitors, as part of what Uncle Edward would call ‘misdirection’.

The library was very impressive. Hodgeman closed the double doors behind them as Nick stared up at the high dome of the ceiling, which was painted to create the illusion of a storm at sea. It was quite disconcerting to look up at the waves and the tossing ships and the low scudding clouds. Below the dome, every wall was covered by tiers of shelves stretching up twenty or even twenty-five feet from the floor. Ladders ran on rails around the library, but no one was using them. The library was silent; two crescent-shaped couches in the centre were empty. The windows were heavily curtained with velvet drapes, but the gas lanterns above the shelves burned very brightly. The place looked like there should be people reading in it, or sorting books, or something. It did not have the dark, dusty air of a disused library.

‘This way, sir,’ said Hodgeman. He crossed to one of the shelves and reached up above his head to pull out an unobtrusive, dun-colored tome, adorned only with the Dorrance coat of arms, a chain argent issuant from a chevron argent upon a field azure.

The book slid out halfway, then came no farther. Hodgeman looked up at it. Nick looked too.

‘Is something supposed to happen?’

‘It gets a bit stuck sometimes,’ replied Hodgeman. He tugged on the book again. This time it came out completely. Hodgeman opened it, took a key from its hollowed-out pages, pushed two books ap

art on the shelf below to reveal a keyhole, inserted the key, and turned it. There was a soft click, but nothing more dramatic. Hodgeman put the key back in the book and returned the volume to the shelf.

‘Now, if you wouldn’t mind stepping this way,’ Hodgeman said, leading Nick back to the centre of the library. The couches had moved aside on silent gears, and two steel-encased segments of the floor had slid open, revealing a circular stone staircase leading down. Unlike the library’s brilliant white gaslights, it was lit by dull electric bulbs.

‘This is all rather cloak-and-dagger,’ remarked Nick as he headed down the steps with Hodgeman close behind him.

Hodgeman didn’t answer, but Nick was sure a disapproving glance had fallen on his back. The steps went down quite a long way, equivalent to at least three or four floors. They ended in front of a steel door with a covered spy hole. Hodgeman pressed a tarnished bronze bell button next to the door, and a few seconds later, the spy hole slid open.

‘Sergeant Hodgeman with Mr Nicholas Sayre,’ said Hodgeman.

The door swung open. There was no sign of a person behind it. Just a long, dismal, white-painted concrete corridor stretching off some thirty or forty yards to another steel door. Nick stepped through the doorway, and some slight movement to his right made him look. There was an alcove there, with a desk, a red telephone on it, a chair, and a guard— another plainclothes policeman type like Hodge-man, this time in shirtsleeves, with a revolver worn openly in a shoulder holster. He nodded at Nick but didn’t smile or speak.

‘On to the next door, please,’ said Hodgeman. Nick nodded back at the guard and continued down the concrete corridor, his footsteps echoing just out of time with Hodgeman’s. He heard behind him the faint ting of a telephone being taken off its cradle and then the low voice of the guard, his words indistinguishable.

The procedure with the spy hole was repeated at the next door. There were two policemen behind this one, in a larger and better-appointed alcove. They had upholstered chairs and a leather-topped desk, though it had clearly seen better days.

Hodgeman nodded at the guards, who nodded back with slow deliberation. Nick smiled but got no smile in return.

‘Through the left door, please,’ said Hodgeman, pointing. There were two doors to choose from, both of unappealing, unmarked steel bordered with lines of knuckle-size rivets.

Hodgeman departed through the right-hand door as Nick pushed the left, but it swung open before he exerted any pressure. There was a much more cheerful room beyond, very much like Nick’s tutor’s study at Sunbere, with four big leather club chairs facing a desk, and off to one side a liquor cabinet with a large, black-enameled radio sitting on top of it. There were three men standing around the cabinet.

The closest was a tall, expensively dressed, vacant-looking man with ridiculous sideburns whom Nick recognized as Dorrance. The second-closest was a fiftyish man in a hearty tweed coat with leather elbow patches. The skin of his thick neck hung over his collar, and his fat face was much too big for the half-moon glasses that perched on his nose. Lurking behind these two was a nondescript, vaguely unhealthy-looking shorter man who wore exactly the same kind of suit as Hodgeman but in a much more untidy way, so he looked nothing like a policeman, serving or otherwise.

‘Ah, here is Mr Nicholas Sayre,’ said Dorrance. He stepped forward, shook Nick’s hand, and ushered him to the centre of the room. ‘I’m Dorrance. Good of you to help us out. This is Professor Lackridge, who looks after all our scientific research.’

The fat-faced man extended his hand and shook Nick’s with little enthusiasm but a crushing grip. Somewhere in the very distant past, Nick surmised, Professor Lackridge must have been a rugby enthusiast. Or perhaps a boxer. Now, sadly, run to fat, but the muscle was still there underneath.

‘And this is Mr Malthan, who is . . . an independent adviser on Old Kingdom matters.’

Malthan inclined his head and made a faint, repressed gesture with his hands, turning them toward his forehead as if to brush his almost nonexistent hair away. There was something about the action that triggered recognition in Nick.

‘You’re from the Old Kingdom, aren’t you?’ he asked. It was unusual for anyone from the Old Kingdom to be encountered this far south. Very few travelers could get authorisation from both King Touchstone and the Ancelstierran government to cross the Wall and the Perimeter. Even fewer would come any farther south than Bain, which was at least a hundred and eighty miles north. They didn’t like it, as a rule. It didn’t feel right, Sam had always said.

But then, this little man didn’t have the Charter Mark on his forehead, which might make it more bearable for him to be on this side of the Wall. Nick instinctively brushed his dark forelock aside to show his Charter Mark, his fingers running across it. The Mark was quiescent under his touch, showing no sign of its connection to the magical powers of the Old Kingdom.

Malthan clearly saw the Mark, even if the others didn’t. He stepped a little closer to Nick and spoke in a breathy half whine.

‘I’m a trader, out of Belisaere,’ he said. ‘I’ve always done a bit of business with some folks in Bain, as my father did before me, and his father before him. We’ve a Permission from the King, and a Permit from your government. I only come down here every now and then, when I’ve got something special-like that I know Mr Dorrance’s lot will be interested in, same as my old dad did for Mr Dorrance’s granddad—’ ‘And we pay very well for what we’re interested in, Mr Malthan,’ Dorrance interrupted him. ‘Don’t we?’

‘Yes, sir, you do. Only I don’t—’ ‘Malthan has been very useful,’ interjected Professor Lackridge. ‘Though we must discount many of his, ahem, traveler’s tales. Fortunately he tends to bring us interesting artifacts in addition to his more colorful observations.’

‘I’ve always spoken true,’ said Malthan. ‘As this young man can tell you. He has the Mark and all. He knows.’

‘Yes, the forehead brand of that cult,’ remarked Lackridge, with an uninterested glance at Nick’s forehead, the Mark mostly concealed once more under his floppy forelock. ‘Sociologically interesting, of course. Particularly its regrettable prevalence among our Northern Perimeter Reconnaissance Unit. I trust it is only an affectation in your case, young man? You haven’t gone native on us?’

‘It isn’t just a religious thing,’ Nick said carefully. ‘The Mark is more of a . . . a connection with . . . how can I explain . . . unseen powers. Magic—’

‘Yes, yes. I am sure it seems like magic to you,’ said Lackridge. ‘But the great majority of it is easily explained as mass hallucination, the influence of drugs, hysteria, and so forth. It is the minority of events that defy explanation but leave clear physical effects that we are interested in—such as the explosion at Forwin Mill.’ He looked over his half-moon glasses at Nicholas.

Dorrance looked at him as well, his stare suddenly intense.

‘Our studies there indicate that the blast was roughly equivalent to the detonation of twenty thousand tons of nitrocellulose,’ continued Lack-ridge. He rapped his knuckles on the desk as he exclaimed, ‘Twenty thousand tons! We know of nothing capable of delivering such explosive force, particularly as the bomb itself was reported to be two metallic hemispheres, each no more than ten feet in diameter. Is that right, Mr Sayre?’

Nick swallowed, his throat moving in a dry gulp. He could feel sweat forming on his forehead and a familiar jangling pain in his right arm and chest.

‘I . . . I don’t really know,’ he said after several long seconds. ‘I was very ill. Feverish. But it wasn’t a bomb. It was the Destroyer. Not something our science can explain. That was my mistake. I thought I could explain everything under our natural laws, our science. I was wrong.’

‘You’re tired, and clearly still somewhat unwell,’ said Dorrance. His tone was kindly, but the warmth did not reach his eyes. ‘We have many more questions, of course, but they can wait until the morning. Professor, why don’t you show Nicholas around the establishment. Let him

get his bearings. Then go back upstairs, and we can all resume life as normal, what? Which reminds me, Nicholas— everything discussed down here is absolutely confidential. Even the existence of this facility must not be mentioned once you return to the main house. Naturally you will see me, Professor Lack-ridge, and the others at dinner, but in our public roles. Most of the guests have no idea that Department Thirteen lurks beneath their feet, and we want it to remain that way. I trust you won’t have a problem keeping our existence all to yourself?’

‘No, not at all,’ muttered Nick. Inside he was wondering how he could avoid answering questions but still get his pass to cross the Perimeter. Lack-ridge obviously didn’t believe in Old Kingdom magic, which was no great surprise. After all, Nick had been like that himself. But Dorrance had voiced no such scepticism, nor had he shown it by his body language. Nick definitely did not want to discuss the Destroyer and its nature with anyone who might seriously look into what it was or what had happened at Forwin Mill.

He didn’t want to dabble in anything to do with Old Kingdom magic, especially without proper instruction, even two hundred miles south of the Wall.

‘Follow me, Nicholas,’ said Lackridge. ‘You, too, Malthan. I want to show you something related to those photographic plates you found for us.’

‘I need to catch my train,’ muttered Malthan. ‘My horses . . . stabled near Bain . . . the expense . . . I’m eager to return home.’

‘We’ll pay you a little extra,’ said Dorrance, the tone of his voice making it clear Malthan had no choice. ‘I want Lackridge to see your reaction to one of the artifacts we’ve picked up. I’ll see you at dinner, Nicholas.’

Dorrance shook Nick’s hand in parting, gave a dismissive wave to Lackridge, and ignored Malthan completely. As Dorrance turned back to his desk, Nick noticed a paperweight sitting on top of the wooden in-box. A lump of broken stone, etched with intricate symbols. They did not shine or move about, not so far from the Old Kingdom; but Nick recognized their nature, though he did not know their dormant power or meaning. They were Charter Marks. The stone itself looked as if it had been broken from a greater whole.

The Ragwitch

The Ragwitch Newt's Emerald

Newt's Emerald Grim Tuesday

Grim Tuesday Sabriel

Sabriel Mister Monday

Mister Monday The Missing

The Missing The Fall

The Fall A Confusion of Princes

A Confusion of Princes Troubletwisters

Troubletwisters Lirael

Lirael Lord Sunday

Lord Sunday Clariel

Clariel Drowned Wednesday

Drowned Wednesday Shade's Children

Shade's Children The Violet Keystone

The Violet Keystone Abhorsen

Abhorsen The Monster

The Monster The Creature in the Case

The Creature in the Case To Hold the Bridge

To Hold the Bridge Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar

Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Above the Veil

Above the Veil Aenir

Aenir Mystery of the Golden Card

Mystery of the Golden Card Superior Saturday

Superior Saturday Sir Thursday

Sir Thursday Castle

Castle Lady Friday

Lady Friday Into Battle

Into Battle Dislocation Space

Dislocation Space Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1)

Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1) Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1

Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1 The Left-Handed Booksellers of London

The Left-Handed Booksellers of London Novel - A Confusion of Princes

Novel - A Confusion of Princes One Beastly Beast

One Beastly Beast A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3

A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3 Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2

Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2 Have Sword, Will Travel

Have Sword, Will Travel Fire Above, Fire Below

Fire Above, Fire Below Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case

Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case The Monster (Troubletwisters)

The Monster (Troubletwisters) Across the Wall

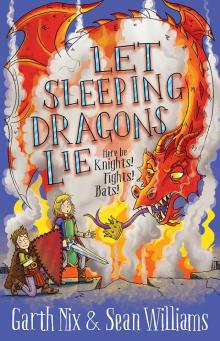

Across the Wall Let Sleeping Dragons Lie

Let Sleeping Dragons Lie![[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/abhorsen_03a_-_across_the_wall_preview.jpg) [Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall

[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall