Goldenhand Read online

Page 2

But they were not common nomads. One was a shaman, with a silver ring around his neck, and from that ring a chain of silvered iron ran to the hand of the second nomad, the shaman’s keeper.

Even without seeing the neck-ring and silver chain, Haral and Aron knew immediately who . . . or what . . . the nomads must be, because the third of their number was neither on horseback, nor was it human.

It was a wood-weird, a creature of roughly carved and articulated ironwood, twice as tall as the horses, its big misshapen eyes beginning to glow with a hot red fire, evidence that the shaman was goading the Free Magic creature he’d imprisoned inside the loosely joined pieces of timber fully into motion. Wood-weirds were not so terrible a foe as some other Free Magic constructs, such as Spirit-Walkers, whose bodies were crafted from stone, for wood-weirds were not so entirely impervious to normal weapons. Nevertheless, they were greatly feared. And who knew what other servants or powers the shaman might have?

“The Guard! Alarm! Alarm!” roared Haral, cupping her hands around her mouth and looking up to the central tower. She was answered only a few seconds later by the blast of a horn from high above, echoed four or five seconds later from the mid-river fort, out of sight in the snow, and then again more distantly from the castle on the southern bank.

“Let me in!” shouted the mountain nomad urgently, even as she looked back over her shoulder. The wood-weird was striding ahead of the two nomads now, its long, rootlike legs stretching out, grasping limbs reaching forward for balance, strange fire streaming from its eyes and mouth like burning tears and spit.

The shaman sat absolutely still on his horse, deep in concentration. It took great effort of will to keep a Free Magic spirit of any kind from turning on its master—a master who was himself kept in check by the cunningly hinged asphyxiating ring of bright silver, which his keeper could pull tight should he try to turn his creatures upon his own people, or seek to carry out his own plans.

Though this particular keeper seemed to have little fear her sorcerer would turn, for she fixed the chain to the horn of her saddle and readied her bow, even though she was still well out of bowshot, particularly with the snow falling wet and steady. Once she got within range, she would get only two or three good shots before her string grew sodden. Perhaps only a single shot at that.

“We can’t let you in now!” called down Aron. He had picked up his crossbow. “Enemies in sight!”

“But they’re after me!”

“We don’t know that,” shouted Haral. “This could be a trick to get us to open the gate. You said you were a messenger; they’ll leave you alone.”

“No, they won’t!” cried Ferin. She took her own bow from the case on her back, and drew a strange arrow from the case at her waist. The arrow’s point was hooded with leather, tied fast. Holding bow and arrow with her left hand, she undid the cords of the hood and pulled it free, revealing an arrowhead of dark glass that sparkled with hidden fire, a faint tendril of white smoke rising from the point.

With it came an unpleasant, acrid taint, so strong it came almost instantly to the noses of the guards atop the wall.

“Free Magic!” shouted Aron. Raising his crossbow in one swift motion, he fired it straight down. Only Haral’s sudden downward slap on the crossbow made the quarrel miss the nomad woman’s gut, but even so it went clear through her leg just above the ankle, and there was suddenly blood spattered on the snow.

Ferin looked over her shoulder quickly, saw Haral restraining Aron so he couldn’t ready another quarrel. Setting her teeth hard together against the pain in her leg, she turned back to face the wood-weird. It had risen up on its rough-hewn legs and was bounding forward, a good hundred paces ahead of the shaman, and it was still accelerating. Its eyes were bright as pitch-soaked torches newly lit, and great long flames roared from the widening gash in its head that served as a mouth.

Ferin drew her bow and released in one fluid motion. The shining glass arrow flew like a spark from a summer bonfire, striking the wood-weird square in the trunk. At first it seemed it had done no scathe, but then the creature faltered, took three staggering steps, and froze in place, suddenly more a strangely carved tree and less a terrifying creature. The flames in its eyes ebbed back, there was a flash of white inside the red, then its entire body burst into flame. A vast roil of dark smoke rose from the fire, gobbling up the falling snow.

In the distance the shaman screamed, a scream filled with equal parts anger and fear.

“Free Magic!” gasped Aron. He struggled with Haral. She had difficulty in restraining him, before she got him in an armlock and wrestled him down behind the battlements. “She’s a sorcerer!”

“No, no, lad,” said Haral easily. “That was a spirit-glass arrow. It’s Free Magic, sure enough, but contained, and can be used only once. They’re very rare, and the nomads treasure them, because they are the only weapons they have which can kill a shaman or one of their creatures.”

“But she could still be—”

“I don’t think so,” said Haral. The full watch was pounding up the stairs now; in a minute there would be two dozen guards spread out on the wall. “But one of the Bridgemaster’s Seconds can test her with Charter Magic. If she really is from the mountains, and has a message for the Clayr, we need to know.”

“The Clayr?” asked Aron. “Oh, the witches in the ice, who See—”

“More than you do,” interrupted Haral. “Can I let you go?”

Aron nodded and relaxed. Haral released her hold and quickly stood up, looking out over the wall.

Ferin was not in sight. The wood-weird was burning fiercely, sending up a great billowing column of choking black smoke. The shaman and his keeper lay sprawled on the snowy ground, both dead with quite ordinary arrows in their eyes, evidence of peerless shooting at that range in the dying light. Their horses were running free, spooked by blood and sudden death.

“Where did she go?” asked Aron.

“Probably not very far,” said Haral grimly, gazing intently at the ground. There was a patch of blood on the snow there as big as the guard’s hand, and blotches like dropped coins of bright scarlet continued for some distance, in the direction of the river shore.

Chapter Two

TWO HAWKS BRING MESSAGES

Belisaere, the Old Kingdom

The hawk came down through the clouds, dodging raindrops for the sheer fun of it, despite having already flown more than two hundred leagues. Born from a Charter-spelled egg and trained for its work since it was a fledgling, the hawk carried a message imprinted in its mind, and with it the burning desire to fly as swiftly as possible to the tower mews in the royal city of Belisaere.

The rain-dodging hawk from the south beat another bird flying in from the north by half a minute, so it was the first to get to Mistress Finney, the chief falconer, while the later hawk had to be content going to the fist of an apprentice.

As a matter of procedure, Mistress Finney checked the anklet on the bird, to see where it had come from, though she already recognized him. She knew all the message-hawks of the Old Kingdom, having raised them herself, even if they were later assigned elsewhere, and became only occasional visitors to the capital.

“From Wyverley College, my lovely,” she said softly, making her own peculiar tongue-clicking sound, one all the hawks knew from the egg. “What a long way, and over the Wall too, my brave one. What’s your message, dear?”

The hawk opened its beak and spoke with a woman’s voice, that of Magistrix Coelle, who taught Charter Magic at Wyverley College, in that strange land beyond the Wall, where magic waned and then disappeared entirely, once too far south.

“Telegram from Nicholas Sayre for the Abhorsen. Extremely urgent,” said the hawk.

“Ah, for the Abhorsen,” said Mistress Finney. “Messenger!”

A seven-year-old page who hoped to become one of the falconer’s apprentices leaped up from the bench where she sat with three others, waiting to take the messages the hawks brought in on

the next part of their journey.

“Yes, Mistress!”

“Find out where the Abhorsen-in-Waiting Lirael is. Tell her I am transcribing an urgent message from Ancelstierre calling for the Abhorsen, and ask her to either come here for it, or to stay wherever she is and you come back and let me know and we will send it on.”

“Yes, Mistress,” said the girl, with a slight hesitation that suggested she didn’t know where to look for Lirael, or why she was looking for Lirael instead of the Abhorsen herself.

“Try Prince Sameth’s workshop first,” said Mistress Finney, after a moment’s thought. “I believe she is often there, for he is making her new hand.”

The girl bent her head in acknowledgment, spun on one foot, and dashed to the stairs.

“Slow down!” called out Mistress Finney after her. “You’ll do no good if you fall to the bottom!”

The clatter of footsteps slowed a little. The falconer smiled and lifted the hawk to the perch that sat on her writing desk. The bird stepped off onto it, watching the woman as she took up her quill, dipped it in the inkwell, and made ready to write.

“Now, my dear, give me the message,” said Mistress Finney to the hawk, who once again spoke, clear and loud in the voice of Magistrix Coelle. Wyverley College, though it lay across the Wall, was close enough that Charter Magic could be wielded there. Though its location meant Ancelstierran technology could not always be relied upon, a telegraph boy’s bicycle would not fail. So it had become the de facto place for Ancelstierran telegrams to be transferred to Old Kingdom message-hawks for onward delivery to authorities in the north.

“Abhorsen, I’ve just received a telegram. It reads ‘TO MAGISTRIX WYVERLEY COLLEGE NICK FOUND BAD KINGDOM CREATURE DORRANCE HALL TELL ABHORSEN HELP STOP THIS FROM NICHOLAS SAYRE STOP VIA DANJERS VALET APPLETHWICK END.’ Now, Dorrance Hall is several hundred miles south, so this seems very unlikely. But I have heard it is some sort of secret government place, so perhaps should be investigated. I have sent telegrams to the Bain Consulate and the Embassy in Corvere, but have not yet had an answer—”

The message ended suddenly. The message-hawks were invaluable, but their minds were small and could not hold very long communications, and their capacity also varied from bird to bird. Unless you knew the particular hawk in question and counted out your words beforehand, it was easy to be cut off in mid-flow. Senders often forgot this in their eagerness to pass on important information. Nor, once a message was impressed, was it an easy matter to start again.

“Well done, my dear,” said Mistress Finney softly to the hawk, carefully drawing a line below the message she had just transcribed and initialing it “MF.” She gestured to one of her apprentices, who came and took the hawk over to its own perch, to be fed some fresh rabbit and to have a drink.

The apprentice who had heard the message from the northern hawk approached her, passing over the paper where he’d written down that bird’s missive.

“This one’s for the King,” he said. “From the Greenwash Bridge Company, at the bridge. Not marked urgent. Follow-up to their earlier report.”

“Spike it for Princess Ellimere,” said Mistress Finney, gesturing at a table adorned with numerous spikes, most of them already impaling message sheets. “She’s coming up this morning, I saw her at breakfast.”

“Not taken to the King immediately?”

“Does no one here pay attention to what is happening in the court we serve?” asked Mistress Finney. It was a rhetorical question, and no one in the mews dared to treat it any other way, remaining silent while hoping they looked suitably attentive. “The King and the Abhorsen left for their holiday this morning. A well-deserved one. Their first holiday! Ever! You could all learn from their example. Hard work—”

She broke off as another hawk flew in, briefly settling on the landing perch before spying Mistress Finney. Upon seeing her, it immediately flew to her fist.

“Hello, my beauty,” said the falconer, forgetting her rant. “Come in from High Bridge, have you?”

Lirael hurried up the steps to the mews. She flexed her replacement hand as she did so, marveling at how well it worked. When her own hand had been bitten off by the Disreputable Dog almost seven months before in order to save her life from the ravening power of Orannis, Sameth had promised to make her a replacement. He had lived up to that promise, and shown he was indeed a true inheritor of the Wallmakers’ engineering ingenuity and magical craft, though it had taken him a long time to get it right, with much tinkering and adjustment. It was only in the last few days that it felt entirely normal to Lirael, really just like her own flesh-and-blood hand.

It was mostly made from meteoric steel, but Sam had gilded the metal, and unasked had added an extra layer of Charter spells atop the ones that made the hand work and even feel like flesh, so it also glowed faintly with a golden light.

Already, many people were calling her Lirael Goldenhand.

Lirael didn’t like the name very much, or the soft glow from her golden fingers. She had worked out how to unravel the part of the spell which provided the light, and planned to do so as soon as she could without hurting Sam’s feelings. Having an artificial magic hand attracted enough attention as it was, without the soft golden light as well.

Though she had to admit to herself it was probably too late to avoid attention. It seemed everyone in Belisaere knew who she was. She’d gone out incognito numerous times, wearing a broad-brimmed hat and gloves and simple, unadorned clothes rather than her distinctive surcoat that bore the silver keys of the Abhorsen on a blue field, quartered with the golden stars of the Clayr on green. But this disguise, if it could be called that, never worked for long. People always discovered her true identity.

Just the day before she’d tried to wander through the market near Lake Loesere but she’d had to give up, because so many people were following her around, and the store traders kept giving her whatever she inquired about for nothing, in gratitude for saving the kingdom from Orannis the Destroyer. Within fifteen minutes she was so overloaded with a sack of blood plums, three bottles of wine, several different cheeses, a wheel-like loaf of fine white bread, and a giant bunch of asparagus that she had to retreat to the palace, trailing a crowd behind her.

She hoped the message from Ancelstierre was going to offer her the possibility of escape from all the attention. In Sabriel’s absence, it was her duty to deal with any Dead or Free Magic creatures, though admittedly the Abhorsen and the King had only consented to go on holiday—to the island of Ilgard—because everything had been largely quiet for the last six months.

Lirael was very eager to take up her duty. Any duty. She still keenly felt the loss of the Disreputable Dog, and being busy was an excellent way to not dwell on that. Or on the difficulties of adapting to a whole new life as the Abhorsen-in-Waiting, with a much older half-sister who was also now her mentor. Though she greatly respected Sabriel, Lirael was also very much in awe of her, and could not easily talk to her about anything other than the work they shared.

Then there was her nephew Sameth and niece Ellimere, though she could never think of them that way, since she was only a little older in years and felt considerably younger in terms of experience with the world. Just being suddenly a part of the ruling family of the Old Kingdom was an almost overwhelming challenge, particularly for someone like Lirael, who was used to spending a great deal of time alone, or in companionable silence with her dear dog.

Now it was nearly impossible for her to be alone, even for a few minutes. The previous six months had been occupied with recovering from her wounding; beginning to learn how to wield the seven bells of the Abhorsen and all the associated magics that went with that art (something she now realized would go on for her entire life; it was not the sort of thing you could ever entirely know); having her replacement hand fitted and fine-tuned, which took absolutely hours; going along with the bare minimum of social activity organized for her by Ellimere, who did not at all behave like a dutiful niece but mu

ch more like a bossy, matchmaking sister; and just trying to fit in with a busy family who knew one another very well.

The messenger girl who was leading the way turned at the top of the stairs and held her finger to her lips.

“Um, please remember to speak quietly and walk slowly,” she said nervously. “So as not to disturb the hawks.”

“I know,” whispered Lirael. She had some experience with the hawks in the Clayr’s mews, high in the rocky peak of Sunfall above the glacier, and she had also visited Mistress Finney’s domain before.

The falconer raised a hand in greeting to Lirael as she climbed the last few steps and emerged into the long room, half open to the sky, the shutters all pulled back to allow easy access for the hawks. The rain had eased and the clouds parted, and the warmish, weak sunshine of early spring was pouring in, a welcome light after the winter’s darkness.

“Greetings, Lirael. You came quickly,” said Mistress Finney. She held out a sheet of thick, linen-rich paper. One of the first things Touchstone and Sabriel had done when restoring the kingdom to rights had been to help the guild of papermakers rebuild several small mills. Touchstone had wanted paper to assist with communications and trade, Sabriel for other reasons. “I have the message ready, and a hawk waiting should you wish to send a reply.”

Lirael took the proffered paper and read the message quickly, and then once again more slowly, to be sure she had fully taken in everything it conveyed. Which wasn’t all that much, when it came to it, save that Sam’s friend Nicholas—Nick—had sent it, requesting the aid of the Abhorsen to deal with a Free Magic creature that was a very unlikely distance south of the Wall.

But then Nick himself was very unlikely, in that he had survived carrying a fragment of Orannis within himself, tainting him with Free Magic, deep into his blood and bone. Or to be more accurate, he hadn’t survived it. He’d died, but had been brought back from Death by the Disreputable Dog, who had also given him the baptismal Charter mark, somehow containing the Free Magic contamination within his body. No one had been quite sure what the result of this would be, and Nick had quickly been taken away to the south of Ancelstierre, where everyone had presumably hoped it wouldn’t matter.

The Ragwitch

The Ragwitch Newt's Emerald

Newt's Emerald Grim Tuesday

Grim Tuesday Sabriel

Sabriel Mister Monday

Mister Monday The Missing

The Missing The Fall

The Fall A Confusion of Princes

A Confusion of Princes Troubletwisters

Troubletwisters Lirael

Lirael Lord Sunday

Lord Sunday Clariel

Clariel Drowned Wednesday

Drowned Wednesday Shade's Children

Shade's Children The Violet Keystone

The Violet Keystone Abhorsen

Abhorsen The Monster

The Monster The Creature in the Case

The Creature in the Case To Hold the Bridge

To Hold the Bridge Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar

Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Above the Veil

Above the Veil Aenir

Aenir Mystery of the Golden Card

Mystery of the Golden Card Superior Saturday

Superior Saturday Sir Thursday

Sir Thursday Castle

Castle Lady Friday

Lady Friday Into Battle

Into Battle Dislocation Space

Dislocation Space Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1)

Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1) Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1

Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1 The Left-Handed Booksellers of London

The Left-Handed Booksellers of London Novel - A Confusion of Princes

Novel - A Confusion of Princes One Beastly Beast

One Beastly Beast A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3

A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3 Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2

Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2 Have Sword, Will Travel

Have Sword, Will Travel Fire Above, Fire Below

Fire Above, Fire Below Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case

Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case The Monster (Troubletwisters)

The Monster (Troubletwisters) Across the Wall

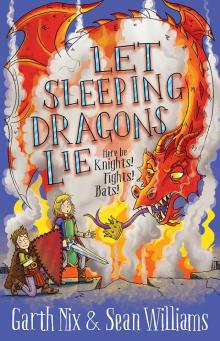

Across the Wall Let Sleeping Dragons Lie

Let Sleeping Dragons Lie![[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/abhorsen_03a_-_across_the_wall_preview.jpg) [Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall

[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall