Mister Monday Read online

Page 2

The two gentlemen pushed back the grille and gestured for the Inspector to step into the elevator. It was lined with dark green velvet and one entire wall was covered in small bronze buttons.

‘We’re not going down, are we?’ asked the Inspector in a small voice.

The taller gentleman smiled, a cold smile that did not reach his eyes. He reached up and his arm clicked horribly as it stretched, growing an extra couple of yards so he could press a button on the very top right-hand side of the lift.

‘There?’ asked the Inspector, awed in spite of his fear. He could feel the Will’s influence working away inside him, but he knew there was no hope of trying to help it now. The words that got away would have to fend for themselves. ‘All the way to the top?’

‘Yes,’ said the two gentlemen in unison as they clanged shut the metal grille.

One

IT WAS ARTHUR PENHALIGON’S first day at his new school and it was not going well. Having to start two weeks after everyone else was bad enough, but it was even worse than that. Arthur was totally and utterly new to the school. His family had just moved to the town, so he knew absolutely no one and he had none of the local knowledge that would make life easier.

Like the fact the seventh grade had a cross-country run every Monday just before lunch. Today. And it was compulsory, unless special arrangements had been made by a student’s parents. In advance.

Arthur tried to explain to the gym teacher that he’d only just recovered from a series of very serious asthma attacks and had in fact been in the hospital only a few weeks ago. Besides that, he was wearing the stupid school uniform of grey pants with a white shirt and tie, and leather shoes. He couldn’t run in those clothes.

For some reason – perhaps the forty other kids shouting and chasing one another around – only the second part of Arthur’s complaint got through to the teacher, Mister Weightman.

‘Listen, kid, the rule is everybody runs, in whatever you’re wearing!’ snapped the teacher. ‘Unless you’re sick.’

‘I am sick!’ protested Arthur, but his words were lost as someone screamed and suddenly two girls were pulling each other’s hair and trying to kick shins, and Weightman was yelling at them and blowing his whistle.

‘Settle down! Susan, let go of Tanya right now! Okay, you know the course. Down the right side of the oval, through the park, around the statue, back through the park, and down the other side of the oval. First three back get to go to lunch early, the last three get to sweep the gym. Line up – I said line up, don’t gaggle about. Get back, Rick. Ready? On my whistle.’

No, I’m not ready, thought Arthur. But he didn’t want to stand out any more by complaining further or simply not going. He was already an outsider here, a loner in the making, and he didn’t want to be. He was an optimist. He could handle the run.

Arthur gazed across the oval at the dense forest beyond, which was obviously meant to be a park. It looked more like a jungle. Anything could happen in there. He could take a rest. He could make it that far, no problem, he told himself.

Just for insurance, Arthur felt in his pocket for his inhaler, closing his fingers around the cool, comforting metal and plastic. He didn’t want to use it, didn’t want to be dependent on the medication. But he’d ended up in the hospital last time because he’d refused to use the inhaler until it was too late, and he’d promised his parents he wouldn’t do that again.

Weightman blew his whistle, a long blast that was answered in many different ways. A group of the biggest, roughest-looking boys sprang out like shotgun pellets, hitting one another and shouting as they accelerated away. A bunch of athletic girls, taller and more long-legged than any boys at their current age, streamed past them a few seconds later, their noses in the air at the vulgar antics of the monkeys they were forced to share a class with.

Smaller groups of boys or girls – never mixed – followed with varying degrees of enthusiasm. After them came the unathletic and noncommitted and those too hip to run anywhere, though Arthur wasn’t particularly sure which category they each belonged to.

Arthur found himself running because he didn’t have the courage to walk. He knew he wouldn’t be mistaken for someone too cool to participate. Besides, Mister Weightman was already jogging backwards so he could face the walkers and berate them.

‘Your nonparticipation has been noted,’ bellowed Weightman. ‘You will fail this class if you do not pick up your feet!’

Arthur looked over his shoulder to see if that had any result. One kid broke into a shambling run, but the rest of the walkers ignored the teacher. Weightman spun around in disgust and built up speed. He overtook Arthur and the middle group of runners and rapidly closed the gap on the serious athletes at the front. Arthur could already tell he was the kind of gym teacher who liked to beat the kids in a race. Probably because he couldn’t win against other adult runners, Arthur thought sourly.

For three or maybe even four minutes after Weightman sped away, Arthur kept up with the last group of actual runners, well ahead of the walkers. But as he had feared, he found it harder and harder to get a full breath into his lungs. They just wouldn’t expand, as if they were already full of something and couldn’t let any air in. Without the oxygen he needed, Arthur got slower and slower, falling back until he was barely in front of the walkers. His breathing became shallower and shallower and the world narrowed around him, until all he could think about was trying to get a decent breath and keep putting one foot approximately in front of the other.

Then, without any conscious intention, Arthur found that his legs weren’t moving and he was staring up at the sky. He was lying on his back on the grass. Dimly, he realised he must have blacked out and fallen over.

‘Hey, are you taking a break or is there a problem?’ someone asked. Arthur tried to say that he was okay, though some other part of his brain was going off like a fire engine siren, screaming that he was definitely not okay. But no words came out of his mouth, only a short, rasping wheeze.

Inhaler! Inhaler! Inhaler! said the screaming siren part of his brain. Arthur followed its direction, fumbling in his pocket for the metal cylinder with its plastic mouthpiece. He tried to raise it to his mouth, but when his hand arrived it was empty. He’d dropped the inhaler.

Then someone else pushed the mouthpiece between his lips and a cool mist suddenly filled his mouth and throat.

‘How many puffs?’ asked the voice.

Three, thought Arthur. That would get him breathing, at least enough to stay alive. Though he’d probably be back in the hospital again, and another week or two convalescing at home.

‘How many puffs?’

Arthur realised he hadn’t answered. Weakly, he held out three fingers and was rewarded by two more clouds of medicine. It was already beginning to work. His shallow, wheezing breaths were actually getting some air into his lungs and, in turn, some oxygen into his blood and to his brain.

The closed-in, confused world he’d been experiencing started to open out again, like scenery unfolded on a stage. Instead of just the blue sky rimmed with darkness, he saw a couple of kids crouched near him. They were two of the walkers, the ones who refused to run. A girl and a boy, both defiantly not in school uniform or gym gear, wearing black jeans, T-shirts featuring bands Arthur didn’t know, and sunglasses. They were either super-hip and ultra-cool, or the exact opposite. Arthur was too new to the school and the whole town to know.

The girl had short dyed hair that was so blond it was almost white. The boy had long, dyed-black hair. Despite this, they looked kind of the same. It took Arthur’s confused mind a second to work out that they had to be twins, or at least brother and sister. Maybe one had to repeat a grade.

‘Ed, call 000,’ instructed the girl. She was the one who had given Arthur the inhaler.

‘The Octopus confiscated my phone,’ replied the boy. Ed.

‘Okay, you run back to the gym,’ said the girl. ‘I’ll go after Weightman.’

‘What for?’ asked

Ed. ‘Shouldn’t you stay?’

‘Nope, nothing we can do except get help,’ said the girl. ‘Weightman’s got a phone. He’s probably already on his way back. You just lie here and keep breathing.’

The last words were directed at Arthur. He nodded feebly and waved his hand, telling them to go. Now that his brain was at least partially functioning again, he was terribly embarrassed. First day at a new school, and he hadn’t even made it to lunchtime. It would be even worse coming back. He would be seen as a total loser and, after a month of the new term, would have no chance of easily catching up or making any friends.

At least I’m alive, Arthur told himself. He had to be grateful for that. He still couldn’t get a proper breath, and he was incredibly weak, but he managed to prop himself up on one elbow and look around.

The two black-clad kids were showing that they could run when they wanted to. Arthur watched the girl sprint through the gaggle of walkers like a crow dive-bombing a flock of sparrows, and vanish into the tree line of the park. Looking the other way, Arthur saw Ed was about to disappear around the high, blank brick wall of the gym, which blocked the rest of the school from view.

Help would be coming soon. Arthur willed himself to be calm. He forced himself up to a sitting position and concentrated on taking slow breaths, as deep as he could manage. With a bit of luck he would stay conscious. The main thing was not to panic. He’d been here before, and he’d come through. He had the inhaler in his hand. He’d just stay quiet and still, keeping panic and fear securely locked away.

A flash of light suddenly distracted Arthur from his slow, counted breaths. It hit the corner of his eye, and he swung around to see what it was. For a moment he thought he was blacking out again and was falling over and looking up at the sun. Then, through half-shut eyes, he realised that whatever the blinding light was, it was on the ground and very close.

In fact, it was moving, gliding across the grass towards him, the light losing its brilliance as it drew nearer. Arthur watched in stunned amazement as a dark outline became visible within the light. Then the light faded completely, to reveal a weirdly dressed man in a very strange sort of wheelchair being pushed across the grass by an equally odd-looking attendant.

The wheelchair was long and narrow, like a bath, and it was made of woven wicker. It had one small wheel at the front and two big ones at the back. All three wheels had metal rims, without rubber tyres, or any sort of tyre, so the wheelchair – or wheel-bath, or bath-chair, or whatever it was – sank heavily into the grass.

The man lying back in the bath-chair was thin and pale, his skin like tissue paper. He looked quite young, though, no more than twenty, and was very handsome, with even features and blue eyes, though these were hooded, as if he was very tired. He had an odd round hat with a tassel on his blond head and was wearing what looked to Arthur like some sort of kung fu robe, of red silk with blue dragons all over it. He had a tartan blanket over his legs, but his slippers stuck out the end. They were red silk too, and shimmered in the sun with a pattern that Arthur couldn’t quite focus on.

The man who was pushing the chair was even more out of place. Or out of time. He looked somewhat like a butler from an old movie, or Nestor from the Tintin comics, though he was nowhere near as neat. He had on an oversized black coat with ridiculously long tails that almost touched the ground, and his white shirtfront was stiff and very solid, as if it was made of plastic. He had knitted half gloves that were unravelling on his hands, and bits of loose wool hung over his fingers. Arthur noticed with distaste that his fingernails were very long and yellow, as were his teeth. He was much older than the man he pushed, his face lined and pitted with age, his white hair only growing on the back of his head, though it was very long. He had to be at least eighty, but he had no difficulty pushing the bath-chair straight towards Arthur.

The two men were talking as they approached. They seemed entirely unaware of Arthur, or uninterested in him.

‘I don’t know why I keep you upstairs, Sneezer,’ said the man in the bath-chair. ‘Or agree to your ridiculous plans.’

‘Now, now, sir,’ said the butler-type, who was obviously called Sneezer. Now that they were closer, Arthur noticed that his nose was rather red and had a patchwork of broken blood vessels shining under the skin. ‘It’s not a plan, but a precaution. We don’t want to be bothered by the Will, do we?’

‘I s’pose not,’ grumbled the young man. He yawned widely and closed his eyes. ‘You’re sure that we’ll find someone suitable here?’

‘Sure as eggs is eggs,’ replied Sneezer. ‘Surer even, eggs not always being what one might expect. I set the dials myself, to find someone suitably on the edge of infinity. You give him the Key, he dies, you get it back. Another ten thousand years without trouble, and the Will can’t quibble cos you did give up the Key to one in the line of heredity, as it were.’

‘It’s very annoying,’ said the young man, yawning again. ‘I’m quite exhausted with all this running around and answering those ridiculous inquiries from up top. How should I know how that bit of the Will got out? I’m not going to write a report, you know. I haven’t the energy. In fact, I really need a nap –’

‘Not now, sir, not now,’ said Sneezer urgently. He shaded his eyes with one dirty, half-gloved hand and looked around. Strangely, he still seemed unable to see Arthur, though he was right in front of him. ‘We’re almost there.’

‘We are there,’ said the young man coldly. He pointed at Arthur as if the boy had suddenly appeared out of nowhere. ‘Is that it?’

Sneezer left the bath-chair and advanced on Arthur. His attempt at a smile revealed even more yellow teeth, some of them broken, but all too many of them sharp and doglike.

‘Hello, my boy,’ he said. ‘Let’s have a bow for Mister Monday.’

Arthur stared at him. It must be an unknown side effect, he thought. Oxygen deprivation. Hallucinations.

A moment later, he felt a hard bony hand grip his head and bob it forward several times, as Sneezer made him bow to the man in the bath-chair. The shock and unpleasantness of the touch made Arthur cough and lose all his hard-won control over his breathing. Now he really was panicking, and he couldn’t breathe at all.

‘Bring him here,’ instructed Mister Monday. With a languid sigh, he leaned over the side of the bath-chair as Sneezer dragged Arthur effortlessly over, using only two fingers to pick the boy up by the back of his neck.

‘You’re sure this one will die straight away?’ Mister Monday asked, reaching out to lift Arthur’s chin and look at his face. Unlike Sneezer, Monday’s hands were clean and his nails trimmed. There was hardly any force in his grip, but Arthur found he couldn’t move at all, as if Mister Monday had pressed a nerve that paralysed his whole body.

Sneezer rummaged in his pocket with one hand, not letting go of Arthur’s neck. He pulled out half a dozen scrunched-up pieces of paper, which hung in the air as if he’d laid them on an invisible desk. He sorted through them quickly, smoothed one out, and held it against Arthur’s cheek. The paper shone with a bright blue light and Arthur’s name appeared on it in letters of gold.

‘It’s him, no doubt at all,’ said Sneezer. He thrust the paper back in his pocket, and all the others went back in as if they were joined together on a thread. ‘Arthur Penhaligon. Due to drop off the twig any minute. You’d best give him the Key, sir.’

Mister Monday yawned again and let go of Arthur’s chin. Then he slowly reached inside the left sleeve of his silk robe and pulled out a slender metal spike. It looked very much like a thin-bladed knife without a handle. Arthur stared at it, his mind and sight already fuzzy again from lack of oxygen. Somewhere in his head, under that fuzziness, the panicked voice that had told him to use his inhaler was screaming again.

Run away! Run away! Run away!

Though the weird paralysis from Monday’s touch had gone, Sneezer’s grip did not lessen for a moment, and Arthur simply had no strength to break free.

‘By the powers vested

in me under the arrangements entered into in the blah, blah, blah,’ muttered Mister Monday. He spoke too quickly for Arthur to make out what he was saying. He didn’t slow down until he reached the final few words. ‘And so let the Will be done.’

As he finished, Monday thrust out with the blade. At the same time, Sneezer let Arthur go and the boy fell back on the grass. Monday laughed wearily and dropped the blade into Arthur’s open hand. Instantly, Sneezer made Arthur wrap his fingers around it, pushing so hard that the metal bit into his skin. With the pain came another sudden shock. Arthur found that he could breathe. It was as if a catch had been turned at the top of his lungs, unlocking them to let air in.

‘And the other,’ said Sneezer urgently. ‘He has to have it all.’

Monday peered across at his servant and frowned. He also started to yawn, but quashed it, taking an angry swipe across his own face.

‘You’re very keen for the Key to leave my possession, even if only for a few minutes,’ said Monday. He’d been about to take something else out of his other sleeve, but now he hesitated. ‘And to give me boiled brandy and water. Too much boiled brandy and water. Perhaps, in my weariness, I have not given this matter quite the thought . . .’

‘If the Will finds you, and you have not given the Key to a suitable Heir –’

‘If the Will finds me,’ mused Monday. ‘What of it? If the reports be true, only a few lines have escaped their durance. I wonder how much power they hold?’

‘It would be safer not to put it to the test,’ said Sneezer, wiping his nose on his sleeve. Anxiety obviously made his nose run.

‘With the complete Key in his possession, the boy might live,’ observed Monday. For the first time he sat up straight in his bath-chair and the sleepy look was gone from his eyes. ‘Besides, Sneezer, it seems odd to me that you of all my servants should have come up with this plan.’

‘How so, sir?’ asked Sneezer. He tried to smile ingratiatingly, but the effect was repulsive.

The Ragwitch

The Ragwitch Newt's Emerald

Newt's Emerald Grim Tuesday

Grim Tuesday Sabriel

Sabriel Mister Monday

Mister Monday The Missing

The Missing The Fall

The Fall A Confusion of Princes

A Confusion of Princes Troubletwisters

Troubletwisters Lirael

Lirael Lord Sunday

Lord Sunday Clariel

Clariel Drowned Wednesday

Drowned Wednesday Shade's Children

Shade's Children The Violet Keystone

The Violet Keystone Abhorsen

Abhorsen The Monster

The Monster The Creature in the Case

The Creature in the Case To Hold the Bridge

To Hold the Bridge Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar

Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Above the Veil

Above the Veil Aenir

Aenir Mystery of the Golden Card

Mystery of the Golden Card Superior Saturday

Superior Saturday Sir Thursday

Sir Thursday Castle

Castle Lady Friday

Lady Friday Into Battle

Into Battle Dislocation Space

Dislocation Space Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1)

Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1) Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1

Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1 The Left-Handed Booksellers of London

The Left-Handed Booksellers of London Novel - A Confusion of Princes

Novel - A Confusion of Princes One Beastly Beast

One Beastly Beast A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3

A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3 Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2

Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2 Have Sword, Will Travel

Have Sword, Will Travel Fire Above, Fire Below

Fire Above, Fire Below Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case

Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case The Monster (Troubletwisters)

The Monster (Troubletwisters) Across the Wall

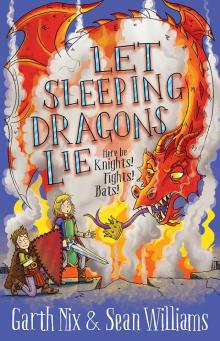

Across the Wall Let Sleeping Dragons Lie

Let Sleeping Dragons Lie![[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/abhorsen_03a_-_across_the_wall_preview.jpg) [Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall

[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall