Abhorsen (Old Kingdom Book 3) Read online

Page 2

But as with any plan, there had already been complications and problems. Two of them were in the House. One was a young woman, who had been sent south by the witches who lived in the glacier-clad mountain at the Ratterlin’s source. The Clayr, who Saw many futures in the ice, and who would certainly try to twist the present to their own ends. The woman was one of their elite mages, easily identified by the colored waistcoat she wore. A red waistcoat, marking her as a Second Assistant Librarian.

The maker of the fog had seen her, black haired and pale skinned, surely no older than twenty, a mere fingernail sliver of an age. She had heard the young woman’s name, called out in desperate battle.

Lirael.

The other complication was better known, and possibly more trouble, though the evidence was conflicting. A young man, hardly more than a boy, curly haired from his father, black eyebrowed from his mother, and tall from both. His name was Sameth, the royal son of King Touchstone and the Abhorsen Sabriel.

Prince Sameth was meant to be the Abhorsen-in-Waiting, heir to the powers of The Book of the Dead and the seven bells. But the maker of the fog doubted that now. She was very old, and once she had known a great deal about the strange family and their House in the river. She had fought Sameth barely a night past, and he had not fought like an Abhorsen; even the way he cast his Charter Magic was strange, reminiscent of neither the royal line nor the Abhorsens.

Sameth and Lirael were not alone. They were supported by two creatures who appeared to be no more than a small bad-tempered white cat and a large black and tan dog of friendly disposition. Yet both were much more than they seemed, though exactly what they were was another slippery piece of information. Most likely they were Free Magic spirits of some kind, bound in service to the Abhorsen and the Clayr. The cat was known to some degree. His name was Mogget, and there was speculation about him in certain books of lore. The Dog was a different matter. She was new, or so old that any book that told of her was long since dust. The creature in the fog thought the latter. Both the young woman and her hound had come from the Great Library of the Clayr. It was likely both of them, like the Library, had hidden depths and contained unknown powers.

Together, these four could be formidable opponents, and they represented a serious threat. But the maker of the fog did not have to fight them directly, nor could she, for the House was too well guarded by both spell and swift water. Her orders were to make sure that they were trapped in the House. The House was to be besieged while matters progressed elsewhere—until it was too late for Lirael, Sam, and their companions to do anything at all.

Chlorr of the Mask hissed as she thought of those orders, and fog billowed around what passed for her head. She had once been a living necromancer, and she took orders from no one. She had made a mistake, a mistake that had led to her servitude and death. But her Master had not let her go to the Ninth Gate and beyond. She had been returned to Life, though not in any living form. She was a Dead creature now, caught by the power of bells, bound by her secret name. She did not like her orders yet had no choice but to obey.

Chlorr lowered her arms. A few feathery tendrils of fog issued from her fingers. There were Dead Hands all around her, hundreds and hundreds of swaying, suppurating corpses. Chlorr had not brought the spirits that inhabited these rotten, half-skeletal bodies out of Death, but she had been given command of them by the one who had. She raised one thin, long arm of shadow and pointed. With sighs and groans and gurgles and the clicking of frozen joints and broken bones, the Dead Hands marched forward, sending the fog swirling all around them.

“There are at least two hundred Dead Hands on the western bank, and fourscore or more to the east,” reported Sameth. He straightened up from behind the bronze telescope and swung it down out of the way. “I couldn’t see Chlorr, but she must be there somewhere, I guess.”

He shivered as he thought of the last time he’d seen Chlorr, a thing of malignant darkness looming above him, her flaming sword about to fall. That had been only the night before, though it already felt much longer ago.

“It’s possible some other Free Magic sorcerer could have raised this mist,” said Lirael. But she didn’t believe it. She could sense the same brooding power out there that she’d felt last night.

“Fog,” said the Disreputable Dog, who was delicately balanced on the observer’s stool. Apart from the fact that she could talk, and the bright collar made of Charter marks around her neck, she looked just like any other large black and tan mongrel dog. The kind that smiled and wagged their tails more than they barked and growled. “I think it has thickened sufficiently to be called fog.”

The Dog; her mistress, Lirael; Prince Sameth; and the Abhorsen’s cat-shaped servant, Mogget, were all in the observatory that occupied the topmost floor of the tower on the northern side of Abhorsen’s House.

The observatory’s walls were entirely transparent, and Lirael found herself taking nervous glances at the ceiling, because it was hard to see if anything was holding it up. The walls were not glass either, or any material she knew, which somehow made it even worse.

But she didn’t want her nervousness to show, so Lirael turned her most recent twitch into a nod of agreement as the Dog spoke. Only her hand betrayed her feelings, as she kept it resting on the Dog’s neck, for the comfort of warm dog skin and the Charter Magic in the Dog’s collar.

Though it was only early afternoon, and the sun still shone directly down on the House, the island, and the river, there was a solid mass of fog on either bank, billowing up in sheer walls that kept on climbing and climbing, though they were already several hundred feet high.

The fog was clearly sorcerous in origin. It had not risen from the river as a normal fog would, or come with lowering cloud. This fog had flowed in from the east and west at the same time, moving swiftly regardless of the wind. Thin at first, it had grown thicker with every passing minute.

A further indication of the fog’s strangeness lay directly to the south, where it stopped sharply just before it might mix with the natural mist thrown up by the great waterfall where the river flung itself over the Long Cliffs.

The Dead had come soon after the fog. Lumbering corpses who climbed clumsily along the riverbanks, though they feared the swift-flowing water. Something was driving them on, something hidden farther back in the fog. Almost certainly that something was Chlorr of the Mask, once a necromancer, now herself one of the Greater Dead. A very dangerous combination, Lirael knew, for Chlorr had probably retained much of her old sorcerous knowledge of Free Magic, combined with whatever powers she had gained in Death. Powers that were likely to be dark and strange. Lirael and the Dog had briefly driven Chlorr away in the last night’s battle on the riverbank, but it had not been a victory.

Lirael could feel the presence of the Dead and the sorcerous nature of the fog. Though Abhorsen’s House was defended by deep running water and many magical wards and guards, she still shivered, as if a cold hand had trailed fingers across her skin.

No one commented on the shiver, though Lirael felt embarrassed at how obvious it had been. No one said anything, but they were all looking at her. Sam, the Dog, and Mogget, all waiting as if she were going to pronounce some great wisdom or insight. For a moment Lirael felt a surge of panic. She wasn’t used to taking the lead in conversation, or in anything else. But she was the Abhorsen-in-Waiting now. While Sabriel was across the Wall in Ancelstierre, she was the only Abhorsen. The Dead, the fog, and Chlorr were her problems. And they were only minor problems, compared to the real threat—whatever Hedge and Nicholas were digging up near the Red Lake.

I’ll have to pretend, thought Lirael. I’ll have to act like an Abhorsen. Maybe if I act well enough, I’ll come to believe it myself.

“Apart from the stepping-stones, is there any other way out?” she asked suddenly, turning south to look at the stones that were just visible under the water, leading out to both eastern and western banks. Stepping-stones was not quite the right name, Lirael thought. Jumping-s

tones would be more appropriate, as they were set at least six feet apart and were very close to the edge of the waterfall. If you missed a jump, the river would snatch you up and the waterfall would throw you down. Down a very long way, under a great weight of crushing water.

“Sam?”

Sam shook his head.

“Mogget?”

The little white cat was curled up on the blue and gold cushion that had briefly been on the observer’s stool, before it was knocked off by a paw and put to better use on the floor. Mogget was not actually a cat, though he had the shape of one. The collar of Charter marks with its miniature bell—Ranna, the Sleepbringer—showed that he was much more than any simple talking cat.

Mogget opened one bright-green eye and yawned widely. Ranna tinkled on his collar, and Lirael and Sam found themselves yawning as well.

“Sabriel took the Paperwing, so we cannot fly out,” he said. “Even if we could fly, we’d have to get past the Gore Crows. I suppose we could call a boat, but the Dead would follow us along the banks.”

Lirael looked out at the walls of fog. She had been the Abhorsen-in-Waiting for only two hours, and already she didn’t know what to do. Except that she had an absolute conviction that they must leave the House and hurry to the Red Lake. They had to find Sam’s friend Nicholas and stop him from digging up whatever it was that was imprisoned deep beneath the earth.

“There might be another way,” said the Dog. She jumped down from the stool and began to tread a circle near Mogget as she spoke, high-stepping as if she were pressing down grass beneath her paws rather than cool stone. On “way” she suddenly collapsed onto the floor near the cat and slapped a heavy paw near the cat’s head. “Though Mogget won’t like it.”

“What way?” Mogget hissed, arching his back. “I know of no way out but the stepping-stones, or the air above, or the river—and I have been here since the House was built.”

“But not when the river was split and the island made,” said the Dog calmly. “Before the Wallmakers raised the walls, when the first Abhorsen’s tent was pitched where the great fig grows now.”

“True,” conceded Mogget. “But neither were you.”

There was the hint of a question, or doubt, in Mogget’s last words, thought Lirael. She watched the Disreputable Dog carefully, but all the hound did was scratch her nose with both forepaws before continuing.

“In any case, there was once another way. If it still exists, it is deep, and it could be dangerous in more ways than one. Some might say it would be safer to cross the stones and fight our way through the Dead.”

“But not you?” asked Lirael. “You think there is an alternative?”

Lirael was afraid of the Dead, but not so much that she could not face them if she had to. She was just not entirely confident in her newfound identity. Perhaps an Abhorsen like Sabriel, in the full flower of her years and power, could simply leap across the stepping-stones and put Chlorr, the Shadow Hands, and all the other Dead to rout. Lirael thought if she tried that herself, she would end up retreating back across the stones and quite likely fall into the river and be smashed to pieces in the waterfall.

“I think we should investigate it,” pronounced the Dog. She stretched out, almost hitting Mogget again with her paws, then slowly stood up and yawned, revealing many extremely large, very white teeth. All of this, Lirael was sure, was to annoy Mogget.

Mogget looked at the Dog through narrowed eyes.

“Deep?” mewed the cat. “Does that mean what I think it does? We cannot go there!”

“She is long gone,” replied the Dog. “Though I suppose something might linger. . . .”

“She?” asked Lirael and Sameth together.

“You know the well in the rose garden?” asked the Dog. Sameth nodded, while Lirael tried to remember if she’d seen a well as they’d crossed the island to the House. She did vaguely recall catching a glimpse of roses, many roses sprawled across trellises that rose up past the eastern side of the lawn closest to the House.

“It is possible to climb down the well,” continued the Dog. “Though it is a long climb, and narrow. It will bring us to even deeper caves. There is a way through them to the base of the waterfall. Then we will have to climb back up the cliffs again, but I expect we will be able to do that farther west, bypassing Chlorr and her minions.”

“The well is full of water,” said Sam. “We’ll drown!”

“Are you sure?” asked the Dog. “Have you ever looked in it?”

“Well, no,” said Sam. “It’s covered, I think. . . .”

“Who is the ‘she’ you mentioned?” asked Lirael firmly. She knew very well from past experience when the Dog was avoiding an issue.

“Someone once lived down there,” replied the Dog. “Someone who had considerable and dangerous powers. There might be some remnant of her there.”

“What do you mean, ‘someone’?” asked Lirael sternly. “How could someone have lived deep underneath Abhorsen’s House?”

“I refuse to go anywhere near that well,” interjected Mogget. “I suppose it was Kalliel who thought to dig into forbidden ground. What use to add our bones to his in some dark corner of the depths?”

Lirael’s gaze flicked across to Sam for an instant, then back to Mogget. She regretted it instantly, for it showed her own doubts and fears. Now that she was the Abhorsen-in-Waiting, she had to set an example. Sam had been open about his fear of Death and the Dead, and his desire to hide out here in the heavily protected House. But he had overcome his fear, at least for now. How could Sam continue to be brave if she didn’t set an example?

Lirael was also his aunt. She didn’t feel like an aunt, but she supposed that it carried certain responsibilities towards a nephew, even one who was only a few years younger than herself.

“Dog!” ordered Lirael. “Answer me plainly for once. Who . . . or what . . . is down there?”

“Well, it’s difficult to put into words,” said the Dog. She shuffled her front paws again. “Particularly since there’s probably no one down there at all. If there is, I suppose that you would call her a leftover from the creation of the Charter, as am I, and so many others of varying stature. But if she is there, or some part of her, then it’s possible she is as she was, which is dangerous in a very . . . elemental . . . way, though it’s all so long ago and really I’m only telling you what other people have said or written or thought. . . .”

“Why would she be down there?” asked Sameth. “Why under Abhorsen’s House?”

“She’s not exactly anywhere,” replied the Dog, who was now scratching at her nose with one paw and totally failing to meet anybody’s eyes. “Part of her power is invested here, so if she were to be anywhere, it’s likely to be here, and that’s where if she were anywhere she’d be.”

“Mogget?” asked Lirael. “Can you translate anything the Dog has said?”

Mogget didn’t answer. His eyes were shut. Somewhere in the space of the Dog’s answer he had curled up and gone to sleep.

“Mogget!” repeated Lirael.

“He sleeps,” said the Dog. “Ranna has called him into slumber.”

“I think he only listens to Ranna when he feels like it,” said Sam. “I hope Kerrigor sleeps more soundly.”

“We can look, if you like,” said the Dog. “But I am sure we would know if he had woken. Ranna has a lighter hand than Saraneth, but she holds tightly when she must. Besides, Kerrigor’s power lay in his followers. His art was to draw upon them, and his downfall was to depend upon it.”

“What do you mean?” asked Lirael. “I thought he was a Free Magic sorcerer who became one of the Greater Dead?”

“He was more than that,” said the Dog. “For he had the royal blood. Mastery of others ran deep in him. Somewhere in Death, Kerrigor found the means to use the strength of those who swore allegiance to him, through the brand he burned upon their flesh. If Sabriel had not accidentally used a most ancient charm that severed him from this power, I think Kerrigor wou

ld have triumphed. For a time, at least.”

“Why only for a time?” asked Sam. He wished he had never mentioned Kerrigor in the first place.

“I think he would eventually have done what your friend Nicholas is doing now,” said the Dog. “And dug up something best left alone.”

No one said anything to that.

“We’re wasting time,” Lirael said finally.

She looked out at the fog on the western bank again. She could feel many Dead Hands there, more than could be seen, though there were plenty enough of those. Rotting sentries, wreathed in fog. Waiting for their enemy to come out.

Lirael took a deep breath and made her decision.

“If you think we should climb down the well, Dog, then that is the way we will go. Hopefully we will not encounter whatever remnant of power lurks below. Or perhaps she will be friendly, and we can talk—”

“No!” barked the Dog, surprising everyone. Even Mogget opened an eye but, seeing Sam looking at him, hastily shut it again.

“What?” asked Lirael.

“If she is there, which is very unlikely, you musn’t speak to her,” said the Dog. “You must not listen to her or touch her in any way.”

“Has anyone ever heard or touched her?” asked Sam.

“No mortal,” said Mogget, raising his head. “Nor passed through her halls, I would guess. It is madness to try. I always wondered what happened to Kalliel.”

“I thought you were asleep,” said Lirael. “Besides, she might ignore us as we ignore her.”

“It is not her ill will I am afraid of,” said Mogget. “I fear her paying us any attention at all.”

“Perhaps we should—” said Sam.

“What?” asked Mogget nastily. “Stay here all nice and safe?”

“No,” replied Sam quietly. “If this woman’s voice is so dangerous, then perhaps we should make earplugs before we go. Out of wax, or something.”

“It wouldn’t help,” said Mogget. “If she speaks, you will hear her through your very bones. If she sings . . . We had best hope she will not sing.”

The Ragwitch

The Ragwitch Newt's Emerald

Newt's Emerald Grim Tuesday

Grim Tuesday Sabriel

Sabriel Mister Monday

Mister Monday The Missing

The Missing The Fall

The Fall A Confusion of Princes

A Confusion of Princes Troubletwisters

Troubletwisters Lirael

Lirael Lord Sunday

Lord Sunday Clariel

Clariel Drowned Wednesday

Drowned Wednesday Shade's Children

Shade's Children The Violet Keystone

The Violet Keystone Abhorsen

Abhorsen The Monster

The Monster The Creature in the Case

The Creature in the Case To Hold the Bridge

To Hold the Bridge Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar

Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Above the Veil

Above the Veil Aenir

Aenir Mystery of the Golden Card

Mystery of the Golden Card Superior Saturday

Superior Saturday Sir Thursday

Sir Thursday Castle

Castle Lady Friday

Lady Friday Into Battle

Into Battle Dislocation Space

Dislocation Space Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1)

Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1) Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1

Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1 The Left-Handed Booksellers of London

The Left-Handed Booksellers of London Novel - A Confusion of Princes

Novel - A Confusion of Princes One Beastly Beast

One Beastly Beast A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3

A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3 Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2

Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2 Have Sword, Will Travel

Have Sword, Will Travel Fire Above, Fire Below

Fire Above, Fire Below Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case

Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case The Monster (Troubletwisters)

The Monster (Troubletwisters) Across the Wall

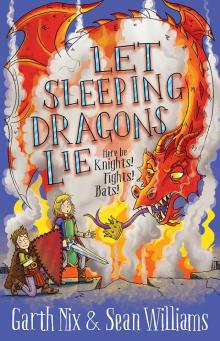

Across the Wall Let Sleeping Dragons Lie

Let Sleeping Dragons Lie![[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/abhorsen_03a_-_across_the_wall_preview.jpg) [Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall

[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall