To Hold the Bridge Read online

Page 3

‘Good,’ said Ishring. ‘Now, draw your sword with your left hand. Take guard.’

Morghan grimaced with the pain, but he drew his sword. His elbow felt like it was burning up inside, but it hadn’t locked up. He could fight left-handed, after a fashion, but Ishring only needed a few passes to disarm him.

‘The elbow is a weak point,’ pronounced the sergeant-at-arms while Morghan bent to pick up his blade. ‘If we used longbows I would say we could not take him. But we don’t, and a crossbow should present no difficulty. He can wield a sword well enough and can manage a poleaxe. He can be trained to be considerably better with both. Is he a useful Charter Mage?’

‘That we shall presently see,’ said Amiel. ‘Come, Morghan.’

‘Yes, milady,’ Morghan replied hurriedly. He nodded thankfully at Ishring, who inclined his head a fraction in return. The sergeant had a hard, scarred face, but his eyes showed considered thought, rather than anything else, and Morghan felt none of the fear that other such faces had provoked in him, back at the Three Coins. Eyes showed true intent, and he had learned young to make himself scarce when he saw the glint of need, anger, or just plain madness in a gaze, usually intensified by too much drink or one of the more vicious substances you could buy in the alleys behind the inn.

Amiel took him to the very center of the courtyard, as far from the wall and the house as possible. There was a large flat paving stone under the dust there. It was some ten feet square and had a bronze grille set in the middle, above a sump or drain to the town sewer.

‘Stand next to the grille,’ instructed Amiel. She walked away from him, off the paving stone. ‘Now, I am going to ask you to cast some basic Charter spells. If you do not know the spell, do not attempt it! Simply tell me that you do not know. Similarly, if you begin a spell and lose your way or the marks begin to overwhelm you, stop at once. I do not wish you to kill yourself, or me, for that matter, by attempting magic beyond your knowledge or skill.’

‘I understand,’ said Morghan. This was also a basic principle that had been drummed into him by Hrymkir, and he had a dim memory of the consequences of overreaching with Charter Magic. His grandmother had tried to bespell his father, to make him stop drinking and become responsible, but it had completely failed. She had been struck blind and dumb as a result and had died soon after. Morghan had been six, but he still remembered her withered hand clutching at him as she tried to tell him something, her words no more meaningful than the cawing of a crow.

Morghan was very careful with Charter Magic.

‘Make a small flame, as if to light a candle,’ called out Amiel. She had retreated another dozen feet. Morghan briefly wondered just how catastrophically other potential candidates had fared with such a simple spell, but forced himself not to dwell on that. Instead he took a deep breath, and reached out for the Charter, immersing himself in the endless flow of marks, visualizing the two he needed, reaching for them as they swam out of the rush of symbols. He caught them and let them run through him, coursing with his bloodstream to the end of his index finger. He held that finger up, and the marks joined and became what they described, a small yellow flame that did not burn his skin, though if he touched it to wick or paper it would set them ablaze.

‘Good,’ said Amiel. ‘Dismiss it.’

Morghan stopped concentrating on the two marks. They retreated back into the great body of the Charter, and the spell instantly faded. A wave of tiredness passed through Morghan as the marks fled, a kind of weary farewell. It must have shown in his face or perhaps he shivered, for Amiel immediately asked if he was able to continue.

‘Yes,’ answered Morghan, as strongly as he could. He felt that his voice hardly reached Amiel, but she nodded.

‘Call forth water from the air, to cup in your hands,’ she instructed.

Morghan knew this one well. It was a simple spell, but could save a traveler’s life. It could be difficult in a very dry place, but the air was moist in Navis.

Once again he reached into the Charter, summoning the marks he needed. This time, when he connected with them, he sketched them in the air with his fingers, completing the tracing by cupping his hands under the glowing signs that hung in the air before him. They turned to sweet water, which trickled through his fingers. Morghan found himself thirsty, and drank.

As before, the conjuration made him tired, but the drink helped a little. He wiped his face with wet fingers, took a breath and looked to Amiel, signaling his acceptance for the next challenge.

‘Call a bird to your hand, from the sky,’ said Amiel.

Morghan hesitated. He knew some of the sequences of marks that identified particular birds, and he knew some marks that could be used together to call to someone, to let them know that the caster wanted to see them. But he did not know any specific spells for calling birds.

‘Uh, I don’t … I don’t know how to do that, milady,’ he said. Better to confess it, he thought, than to accidentally summon a thousand birds, or perhaps something far more dangerous. There were Free Magic creatures that could fly, and were not deterred by running water. Sometimes such creatures slept beneath cities, or had been imprisoned in bottles or jars, and a slipshod Charter spell could help them escape their confinement.

‘You are wise,’ said Amiel. ‘Do you know the spell of the silver blades?’

‘Yes,’ answered Morghan. This was a very old, much-used spell for combat. He could feel the three marks already, rising up from the swirl of the Charter, pressing to come into his mind and mouth.

‘Cast against the pell,’ said Amiel.

Morghan raised his hand and pointed at the wooden post. It was already almost hacked in half by the attentions of Ishring and Morghan’s own efforts. The sergeant had left it now, and the space was clear around it.

‘Anet! Calew! Ferhan!’ roared Morghan, the use-names of the marks flying from his mouth, leaving the burn of power against his lips. The marks became silver blades as they flashed across the gap between him and the pell, and then the timber exploded as they struck, the top of the post bouncing across the yard in a cloud of dust and wood chips.

‘That will do,’ said Amiel.

Morghan blinked, wiped his sweating forehead, and tried to suck in air without making it too obvious that he was absolutely shattered. His legs felt weak and barely able to support his weight and he wished there was something he could unobtrusively lean against.

‘You have done well,’ said Amiel. She surprised Morghan by taking his arm and helping him walk back toward the house. He tried to not lean on her, but found he was too exhausted. In any case, she seemed to have no difficulty holding him up.

‘I have tested many a cadet who has fainted after their first spellcasting,’ said Amiel as they slowly ascended the stairs in the rear tower. ‘Few manage three spells in so short a time with no allowance for rest, and I think on only two occasions has a cadet candidate managed four.’

‘Will you … will I … may I join the company?’ croaked Morghan as they came back out on the main landing, above the grand stair. It was much as they had left it. Famagus had not returned to sleep on the step, but instead was sitting up and writing in a different, but equally large, ledger.

‘Yes,’ said Amiel. She sat him down on the top step, next to Famagus. ‘You are accepted as a cadet of the Worshipful Company of the Greenwash & Field Market Bridge.’

‘Sign here,’ said Famagus, balancing the open ledger on Morghan’s knees.

Everything was already written out, in neat lines of script, indenturing Morghan, son of Hirghan and Jorella, to the Company for the next five years in the position of cadet, one share of the company to be put in trust as a surety for his conduct and application, a further share to be issued should he on the completion of four years be commissioned as a Bridgemaster’s Second.

Morghan took the pen, signed with a shaking hand, and passed out.

Though he had been allowed to sleep on the step for an hour or so after he signed his indentures, his

awakening marked the beginning of Morghan’s training. Even before he rubbed his eyes, a passing Bridgemaster’s Second whose name he missed thrust a book called Company Orders into his hand, with the instruction that he was to read it before he next saw the Bridgemistress, as among many other things, it detailed the comprehensive duties of a cadet. He had barely opened this small but thick volume, printed very clearly and precisely on onionskin paper, before a different Bridgemaster’s Second took his elbow and led him away to another part of the main house, where he met someone he initially thought was called Sutler before he realized that was her title, as she was in charge of a veritable treasure trove of clothing and equipment.

Before he could protest, Morghan was stripped to his underclothes by the Sutler’s assistants, one of whom was a woman not much older than he was, and when the Sutler saw the state of disrepair of the undergarments, though they were clean, those came off too.

Morghan almost lashed out at his helpers as they stripped him, but just in time he realized that they were not trying to humiliate him, just trying to get on with their jobs as quickly as possible and that the Sutler herself was piling up new undergarments and other clothes on the table, ready for Morghan to put on immediately.

Newly attired in the livery of the Company, Morghan was loaded up with more new stuff than he had ever had before, the assistants piling things onto his outstretched arms as the Sutler wrote them in her ledger. When the pile of five undergarments, three leather tunics, six sleeveless shirts, six sleeves with laces, one pair breeches short, two pairs breeches long, one heavy greasy wool cloak with enamel Company badge, one light cloak lined with silk, two leather jerkins, four belts, one pair doeskin boots, one pair metaled leather boots, one pair woolen slippers, one broad felt hat, one cap, six pairs assorted neckerchiefs, and one sewing wallet reached Morghan’s chin, he was tapped on the elbow by the first Bridgemaster’s Second, back again, and led out of the Sutler’s store to yet another part of the house, this time a long, high-ceilinged room that had to be a wing all on its own. It was lined with trestle beds, forty along one wall and thirty on the other, each of them with two chests at the foot of the bed, a large one and a smaller one with leather straps.

Morghan was told this was the barracks, which was usually about half full as the greater majority of the company’s people lived in private accommodations in the town, and the senior officers had their own chambers above. But when on guard duty, this was home for a week at a time, and for their first year at least, the cadets were required to live in the barracks.

‘Not that you’ll be here long,’ said the Second, whose name Morghan still didn’t know and didn’t want to ask. ‘You’re joining the Winter Shift, under Bridgemistress Amiel, and you move out tomorrow at dawn.’

‘How many Shifts are there?’ asked Morghan. Under the Second’s direction, he chose a bed, even if it was only for one night.

‘Four, of course. I’m in Summer, under Bridgemaster Korbin. But I was loaned to Winter, under Amiel, last year. She’s a tough one.’

Morghan must have looked worried, because the Second added, ‘She’s just, mind you. Or, not exactly just … I mean she’s … ah … just do what you’re told willingly and you’ll be all right. Now, get your things stowed. Your small chest will go with you, so make sure you have everything you’ll need in it. I’ll be back to take you to the armory for your weapons and hauberk, the refectory for supper, and then the Bridgemistress wants to see you before her evening rounds.’

Morghan muttered his thanks and immediately packed away all the things he had been given, carefully sorting and inspecting them. Everything went into the smaller chest. He had nothing personal to put in the larger one, and he belatedly realized that the Sutler had not returned his former clothes, his ill-fitting mail shirt or his blunt training sword. He supposed they might be sold, and that would be part of the business of the company, or perhaps the Sutler’s personal perquisite. In either case, he didn’t care. They were a reminder of a life that he hoped he had left behind forever.

After a final, satisfied look at his well-packed traveling chest, and mindful of the Second’s parting comment about the Bridgemistress wanting to see him, Morghan tried to read as much as he could of Company Orders before he was led away again.

He managed thirty-six pages before he was hustled out of the barracks to become reacquainted with Sergeant Ishring in the armory: a large, split-level room that opened out into a smaller courtyard of yet another wing of the main house. It held more weapons and armor than Morghan had ever seen in one place before, including the large swordsmith’s that had been near the Three Coins and was supposed to be one of the best in Belisaere.

Ishring explained that while he was Sergeant of the Winter Shift, and so would be training Morghan on the road and at the bridge, command of the house had been formally handed over to the Spring Shift just that past hour, and thus it was Sergeant-at-Arms Corena who now ran the armory. So it was she who carefully measured him for a hauberk of ringed mail that would be adjusted and ready for him to pick up after he saw the Bridgemistress that evening, a promise made concrete by the sound of the smiths working at the forge in the courtyard outside the armory.

Morghan was also issued a poleaxe; a sword, a proper long hangar with a rounded point; two daggers, thin and merciless; a knife of more general purpose and rougher make; and the number of a crossbow that would be his to use and care for, but when not in active use would be stored in the armory wagon or, when they reached the bridge, in the fort on the northern bank or the midriver bastion, depending on his assigned station.

‘You can ride, I suppose?’ asked Ishring as he helped Morghan back to the barracks with his gear.

‘Yes,’ said Morghan. ‘I … I worked a lot with horses.’

He did not say that this consisted mostly of mucking out the stables, cleaning tack, and wiping down and brushing the mounts of guests at the inn. But he had been taught to ride properly when he was very young and his grandmother was still alive, and though he had not ridden far since, he had had plenty of practice taking horses in and out of the city, the Three Coins being located near the Western Wall, a convenient place to exchange horseback for a litter or to go afoot, horses being prohibited in most parts of Belisaere.

‘We walk, mostly,’ said Ishring. ‘With the wagons. But there’s always a mounted patrol as well, and cadets and guards alike take their turn.’

‘How long does it take to reach the bridge?’ asked Morghan.

‘You mean, “How long does it take to reach the bridge, Sergeant,”’ said Ishring. ‘You’re a cadet now, not a visitor. Don’t forget.’

The sergeant’s tone was formal, but not aggressive.

‘Beg pardon, Sergeant,’ said Morghan. He felt his back straighten by reflex as he asked again, ‘How long to reach the bridge, please, Sergeant?’

‘Sixteen days, weather permitting,’ said Ishring. ‘Twenty or more if there’s snow. Now, in barracks, your poleaxe goes across behind the bedhead, you see the brackets? You wear sword and knife at all times, and daggers as well when mustered to the guard. When you get your hauberk and gambeson, you will wear them at all times, except when you’re asleep, when they go on the stand here, half-unlaced and ready to put on. When I think you’re used to the weight, you can wear leather and cap when not on duty, but not until I say so. You’ll learn more about your duties and service on the march, from tomorrow. Understand?’

‘Yes, Sergeant,’ said Morghan. He spoke softly, as he usually did, a habit born of not wanting to draw attention to himself at the inn.

‘I can’t hear you!’ roared Ishring. ‘Do you understand me?’

‘Yes!’ Morghan roared back, surprising himself.

‘Good,’ said Ishring, in conversational tones. ‘Ah, here comes Second Nerrith to show you to supper. Welcome to the company, Cadet Morghan. Good evening, Second Nerrith.’

‘Good evening, Master Ishring,’ said Nerrith, who was the first Bridgemaster’s Second

who had rushed him hither and yon. She didn’t look much older than him, but had far more self-assurance. ‘Cadet Morghan.’

Ishring departed. As he strode away, Morghan relaxed a little, but not too much. He remembered Hrymkir’s stories of life in the Royal Guard, and though he didn’t fully understand the hierarchy of the company, he’d read enough in his new book to understand that the Bridgemaster’s Seconds were junior officers and could not only give any cadet orders, but also subject them to a long list of punishments for any perceived infraction of courtesy or duties. He had not read about the status of the sergeants-at-arms, but it was clear they were to be obeyed. As for the Bridgemistress herself, she had already attained a status for Morghan as a figure of vast authority, who was not only to be obeyed, but worshipped.

‘Have you read the Orders?’ asked Nerrith.

‘Ah, some of it,’ said Morghan. Belatedly he added, ‘Bridgemaster’s Second.’

‘Just call me Second,’ said Nerrith. ‘The Bridgemistress is “milady” or “Bridgemistress.” Cadets call the sergeants “Sergeant.” The guards you address by name, or “guard,” if you absolutely have to. You’ll need to learn everyone’s name as quickly as you can. I’ll get you a copy of the full roster, but you’ll need to try and fix the names in your head as you meet people. Do you have any questions right now? We have a few minutes before the first sitting for supper.’

‘Are there many cadets?’ asked Morghan. He was a little anxious about how he might get on, particularly after his experiences at the Academy. Working in the stables was not conducive to good relations with the richer and more important students with their highly inflated views of their own standing and how it might be affected by deigning to even notice, let alone befriend, a stableboy, even if his family had once been important at court.

The Ragwitch

The Ragwitch Newt's Emerald

Newt's Emerald Grim Tuesday

Grim Tuesday Sabriel

Sabriel Mister Monday

Mister Monday The Missing

The Missing The Fall

The Fall A Confusion of Princes

A Confusion of Princes Troubletwisters

Troubletwisters Lirael

Lirael Lord Sunday

Lord Sunday Clariel

Clariel Drowned Wednesday

Drowned Wednesday Shade's Children

Shade's Children The Violet Keystone

The Violet Keystone Abhorsen

Abhorsen The Monster

The Monster The Creature in the Case

The Creature in the Case To Hold the Bridge

To Hold the Bridge Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar

Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Above the Veil

Above the Veil Aenir

Aenir Mystery of the Golden Card

Mystery of the Golden Card Superior Saturday

Superior Saturday Sir Thursday

Sir Thursday Castle

Castle Lady Friday

Lady Friday Into Battle

Into Battle Dislocation Space

Dislocation Space Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1)

Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1) Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1

Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1 The Left-Handed Booksellers of London

The Left-Handed Booksellers of London Novel - A Confusion of Princes

Novel - A Confusion of Princes One Beastly Beast

One Beastly Beast A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3

A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3 Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2

Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2 Have Sword, Will Travel

Have Sword, Will Travel Fire Above, Fire Below

Fire Above, Fire Below Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case

Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case The Monster (Troubletwisters)

The Monster (Troubletwisters) Across the Wall

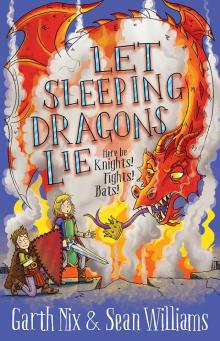

Across the Wall Let Sleeping Dragons Lie

Let Sleeping Dragons Lie![[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/abhorsen_03a_-_across_the_wall_preview.jpg) [Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall

[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall