A Confusion of Princes Read online

Page 3

But even equipped with the mantas, we could not successfully land, at least not alive. While the ninth planet had been partially shaped to support life, it still didn’t have much of an atmosphere, and our glide path would slow our approach speed to only four or five hundred kilometres an hour.

For the final descent, Haddad had also equipped us with contragravity harnesses, military-issue ones as worn by mekbi troopers rather than the superior variety used by Princes. Unfortunately, without the additional internal power supplies of these troopers, our contragravity harnesses would operate for only three minutes.

In the airlock, Haddad assured me this would be plenty of time and everything would work out. I was a bit annoyed again that he couldn’t tell me the probability of success, even though I knew we needed a priest from the Aspect of the Cold Calculator, who specialises in working out the odds. Because in the biosim Prince Garikm had at least a dozen Cold Calculators, I presumed every Prince would be given a whole stable of probability advisers. Of course, I was wrong about that, as I was about so many other things.

‘Have you used a manta before?’ I asked. We had talked at length about the Princes Haddad had served in the past. He told me all of them still lived, and the most recent hadn’t even died once, a most remarkable statistic. Though Haddad did not say so, I was beginning to understand that I had been assigned a very experienced and senior Master of Assassins, who was far more capable than I could have expected so newly emerged from my candidacy. As I would later learn, most new Princes were assigned apprentice assassins who were promoted to Master when they joined their Prince, a fact unsurprisingly linked to the high mortality rate of neophyte Princes. Most of whom, like me, would have begun their short Princely careers thinking that competition between Princes was like an ordered game, when in fact, as Haddad explained, it was a brutal struggle in which Princes did whatever they could get away with.

‘Once in training, three times operationally,’ replied Haddad. ‘The manta is a well-proven piece of equipment, and the environment of Kwanantil Nine is within deployable parameters. I would prefer better suits, as the atmosphere recycling in these is inferior and there is small margin for delay. However, it could be worse. Follow my lead, Highness, and we will soon see you connected to the Imperial Mind and established as a cadet of the Naval Academy.’

I nodded, stiff necked, and thrust my hands into the manta’s nerve sockets behind its head, establishing contact, as they had no Psitek controls. It rippled under my fingers, eager to launch into space and extend its body. I held it back using the slight variations in finger pressure that Haddad had mentally transmitted to me earlier as a tactile memory.

To aid our departure, Haddad had bypassed the safety devices to allow us to use the emergency jettison feature of the large airlock, blowing off the outer door and using the air contained within to shape our initial vector.

:Prepare for ejection: sent Haddad.

:Ready:

The outer door blew off, and out we went in a cloud of air and water vapour. The starfield spun around me, and for a moment I lost my bearings. Then I saw Haddad, his manta already rippling out like a dark shadow all around him. I lost him again for a moment as my own manta righted itself, but a minute later my internal guidance kicked in, my fingers pulsed at the manta’s nerve controls, and I was lying on the back of a fully extended manta that was gently pulsing its gas glands to match Haddad’s course and velocity.

I glanced over my shoulder and saw Beyond the Veil of Time receding on a tangential course as its slow but inexorable thrusters built its speed back up. It was still recognisable as a dull nickel-iron asteroid, which it mostly was, the ship parts being tunnelled inside, but soon it would be no more than another fading star in the great swath of light and dark all around me.

We were twenty-eight hours in transit to Kwanantil Nine. This turned out to be a long time to spend in a vacuum suit on the back of a manta, cut off from all communication. Haddad had insisted that we should use neither mindspeech nor Mektek commpulse unless absolutely necessary.

I had never been left alone for so long in the company of nothing but my own thoughts, such as they were. I was still too newly hatched as a Prince, and devoid of experience, to think deeply on any matters save my own immediate concerns. Even there, I lacked the knowledge to properly evaluate my position and prospects. Perhaps it was just as well.

Instead, I dreamed, fantasising about my future life, setting my own no doubt glorious exploits against a background of how I imagined the galaxy was, rather than on its actuality. The next year, which I would necessarily spend as an officer cadet in the Navy, occupied only a few minutes of my imagining, because I knew nothing at all about that life. Instead, I skipped over this immediate future and dreamed of something very like the first episode of Prince Garikm’s Achievements, with me being the heroic singleship pilot, intervening at just the right moment to win a titanic battle against the Naknuk, leading to honours, the adulation of my peers, and in Garikm’s case (in episode 39) becoming the youngest ever grand admiral of the Imperial Fleet. Naturally, this would then lead to the Imperial Throne. I would be Emperor, master of the greatest interstellar Empire of all time!

As with so much else, my fantasies were built on ignorance. It took me some time to learn that the ranks and honours so eagerly sought by Princes often did not bring the adulation of peers, but instead jealousy, resentment, and a great increase in backstabbing.

Wrapped in dreams, I found the time passed slowly. Every now and then I had to correct the manta’s course and velocity, with suitable bursts of gas from its glands and vents, keeping station behind Haddad, who led the way.

Then, almost as if the twenty-eight hours had been but a blink of the eye, we were entering the thin and gloomy atmosphere of the planet. The mantas went into automatic reentry mode, and as instructed, I drew in my arms and legs to huddle in the most thermally protected portion of the manta, in the centre of its back.

The ride down was faster and much more difficult than I had expected. The manta bucked and spun, and several times I was almost thrown off as a sudden tilt threatened to upset the manta and make me the recipient of white-hot lances of superheated air rather than its ablative silicon underbelly.

But the manta’s design was good, Haddad had grown it well, and my balance and strength were of course far better than any normal human’s. I held on, kept the trim, and like a falling star I shot through the heavens, until at ten thousand metres the manta and I parted company, me into free fall and it into a long glide that would end in a not very spectacular explosion somewhere on the horizon.

Haddad had separated some distance away. Though I had never skydived, my body knew how to do it, one of the many basic skills programmed into mind and muscle memory. As with all such programmed skills, while I possessed the basics, I had neither style nor noticeable flair. Nevertheless, I starfished to correct my spin and put my contragrav harness on standby as Haddad speared toward me, matching my descent rate with real skill and experience.

:Activate harness:

My harness suddenly bit into my flesh as the antigravity coils warmed up. But still I plummeted down, the thin air hardly slowing my fall, the antigrav slow to build. The dark ground beneath grew closer and closer . . . a lot closer a lot faster than I thought it should be. I was just about to scream out something both verbally and in mindspeech when Haddad’s mental voice sounded calmly inside my head.

:Emergency full reversal on my mark: sent Haddad, and then a moment later :Mark:

My harness whined, the straps cut deeper still, and suddenly I felt as if I were no longer falling, though my internal instrumentation recorded that I was in fact still descending, albeit slowly. The ground was close enough to discern some details, though only through augmented eyes. Kwanantil Nine was a long way from its star, and neither of its two moons had yet been turned into an auxiliary sun, so the light was akin to a dim twilight on a world shaped to the standard of old Earth.

&nbs

p; :We are being tracked: sent Haddad, a focused mind-send to me, which he immediately followed by a wider, more powerful cast.

:Prince Khemri <> relay to Imperial Mind:

That was directed at the installation I could now see clearly below, a typical Imperial surface cube some two hundred meters a side, made of local dirt bonded together by Bitek agents, internally reinforced with Mektek armour and Psitek force shields. It would just be an entry building, with the Naval Academy proper located many hundreds of metres below. Sometimes a thick layer of earth and stone could prevail as a defence, even when Imperial tek failed.

The top of the cube bristled with various autoguns and launchers, many of which were now pointing at me. Faint orange flashes were cycling in the corner of my eyes, warning me of targeting lock-ons, till I noticed the warnings and turned them off. We were so close at that point that my internal systems would only be able to provide enough warning time for me to know I was going to be vapourised a microsecond before it happened.

Fortunately, Haddad’s mind-send worked, though the last part about relaying to the Imperial Mind wasn’t true, unless the priests in the Academy did it for us. I had no household priests to relay. I guessed Haddad had sent that so that any Prince who did think I was an easy target would have second thoughts, just in case I had an unseen vessel somewhere nearby loaded with priests relaying everything.

We landed a kilometre from the cube, my contragrav harness losing power in the last five metres so that my planned perfect landing ended up being rather less dignified as I sprawled in the dark-blue earth. I barely had time to stand up before we were ringed by mekbi troopers, the Bitek human-insect hybrid grunt infantry of the Empire, clad in their dark Mektek armour. I could sense their internal systems and active weapons, and could almost, but not quite, make out the mental chatter between them. But it was all a distant whisper, and I couldn’t hear their command channel, either, as that was locked into Naval service only and their immediate commander.

Who, as it turned out, was a senior cadet annoyed at having an unscheduled arrival during her final watch. She landed in front of me as if she had come down a single step, and her elegance wasn’t solely due to her vastly superior zero-G equipment. Her Master of Assassins, I noted, stayed above, and there were several other blips showing up in my Mektek and Psitek scans that suggested assassin apprentices in a standard formation above and behind the mekbi troopers.

‘Prince Khemri,’ she said with distaste, not even bothering to raise her gold-mirrored visor, as would have been polite. ‘State your business.’

‘Joining the Navy,’ I replied. I didn’t raise my visor either. ‘Who are you?’

I was just answering rudeness with rudeness, since I already knew who she was. Princes radiate their identity to Imperial friendlies through Psitek, via numerous wide and narrow Mektek comm bands and also, when in the appropriate atmosphere, via coded pheromones.

So I knew she was Prince Atalin, that she was three years older than me, an advanced cadet. Not only was she a cadet officer of this Naval Academy, but she was in fact the Senior Cadet Officer, winner of the Sword of Honour in her first year and holder of numerous prizes for coming in top in various subjects, all of this pretty much adding up to her being the best thing to deign to attend this academy since the foundation of the Empire.

And she was a member of House Jerrazis, a group of Princes led by Rear Admiral Prince Jerrazis the fifth, who I could look up if I chose to but didn’t right at that moment. Which was, of course, a mistake.

‘You know who I am,’ she said, and raised her visor, though it wasn’t out of politeness. It was so she could wrinkle her nose to indicate her distaste for such a lowly creature as myself.

I didn’t raise my own visor. It seemed a better snub than wrinkling my own nose back at her.

Even though I could see only the narrow band of her face from halfway up the nose to just above her sharp brown eyes, I was immediately struck with a sense of familiarity. But I knew I couldn’t have met her before. I’d never met any other Princes.

So why did she look so familiar?

‘You are logged as a visitor,’ she replied. ‘If you depart from the authorised route to the temple, you will be in breach of Naval regulations and may be detained.’

She sent something to someone else by mindspeech at the end of that, but I couldn’t pick it up. I presumed it was a communication to the Imperial Mind. Soon I would be connected too, and would not be so much in the dark.

‘Uh, what is the authorised route?’ I asked.

Atalin didn’t bother to reply. She just sniffed, her visor slid down, and she waved the mekbi troopers away before suddenly taking off to jet back to the cube. Her Master of Assassins lingered for a minute or so, looking down at Haddad, and again I caught the edge of a whisper of mental communication. It must be odd, I thought, for assassins to work against each other when they were also all priests of the same Aspect, but I suppose it was no more strange than the competition of Princes. The whole Empire was based on this competition, after all.

‘I have the route. We must get inside before our oxygen reserves fail,’ said Haddad when we were alone. ‘The atmosphere here is not sufficient to sustain even augmented life.’

I hadn’t noticed that my suit was indicating it could no longer refresh my air and that it was drawing on the small reserve supply of oxygen.

‘How dare they just leave us here!’ I spluttered, wasting some of that precious oxygen. ‘I will protest!’

‘Not recommended, Highness,’ said Haddad briefly. He was already pulling at my elbow, urging me forward.

‘But I am a Prince of the Empire!’

That cry sounded like a pathetic bleat, even to my own ears. Haddad did not reply, so I stopped the bleating and increased my pace.

We entered a pedestrian airlock of the cube two minutes before my emergency oxygen reserve ran out, even though I had tuned my metabolism to operate on a very low pressure indeed. It was pleasant to reoxygenate, but as I was learning could be expected, Haddad did not let me dwell on it. He hustled me through the airlock, past a guard of mekbi troopers who slammed satisfactorily to attention as I passed, and straight to a drop shaft. There he paused to test that it was in fact operating— the fail-safes had not been subverted—and that it would provide a suitably sedate descent some twenty floors down to the reception rooms of the Temple of the Emperor in Hier Aspect of the Noble Warrior.

I felt some slight relief as we entered the main reception hall, though I did not relax my guard. I had learned that lesson already. Here, instead of waterfalls to be silenced, groups of acolytes struggled to keep dozens of crystal chandeliers in place by Psitek energy alone, in yet another test of their suitability to become full priests. As they stood directly under each huge, spiky array of lights, there was considerable incentive for the acolytes in each group to work together.

We passed through without incident into the next chamber. This vast room resembled a junkyard, save for a central avenue that was kept clear. Everywhere else, acolytes laboured over complex Mektek devices, though it was not clear to me what was being tested, for the acolytes did not seem to be in any danger, unlike those in the outer room.

I breathed easier as we reached the end of the chamber, presuming that we would now enter the temple proper and I would be safe, at least momentarily, from assassination.

But passing through the next gateway hub, we did not enter another reception room. Instead, what lay ahead was one of the temple’s utility chambers, part of its Bitek support systems, a vast organic-waste recycling hall that mimicked the ecology of some fecund planet, presenting us with a bubbling swamp of rotten organic matter and decomposition jelly, to be crossed via a very narrow transparent bridge that was several hundred metres long.

Haddad paused as we entered this chamber.

:Maximum Alert, Highness. There

will be assassins here:

I looked around, noting the closer acolytes in their hooded Bitek-repellent robes, who were raking the muck with gene-sorting staves that resembled living tree branches crossed with crocodile tails.

Some of those acolytes were almost certainly not from the Aspect of the Noble Warrior. They would be apprentice assassins, or even Masters, since I couldn’t see the size of the transparent panels in their heads under their hoods.

The deintegration wand slipped into my hand and I drew the phage emitter from my boot. Haddad set off ahead of me, and I stepped onto the bridge.

3

THE ATTACK CAME when we were almost exactly halfway across the bridge, but not from any of the acolytes I had been carefully watching. I got the barest time sliver of warning from having my senses ramped up to maximum (a level that could not be sustained for very long) and so was able to dive into the swamp a fraction of a second before the bridge was smashed into pieces by the sudden eruption of a Bitek penetrator beneath it, a five-metre-long diamond-hard spike normally to be found as a ship weapon mounted on the front of a Mektek missile.

I saw the penetrator through a metre or more of Bitek gloop, my arms flailing as I tried to regain the surface. The stuff was sticky, and denser than water. I was still in my suit, but the visor was open, so defensive membranes had automatically slid across my eyes and ears. I could feel the pressure of the slime. Even if it was only the regular environmental gel that was designed to break down organics. There was also a good chance that this was some restructured assassination variety. I kicked harder and broke free.

The Ragwitch

The Ragwitch Newt's Emerald

Newt's Emerald Grim Tuesday

Grim Tuesday Sabriel

Sabriel Mister Monday

Mister Monday The Missing

The Missing The Fall

The Fall A Confusion of Princes

A Confusion of Princes Troubletwisters

Troubletwisters Lirael

Lirael Lord Sunday

Lord Sunday Clariel

Clariel Drowned Wednesday

Drowned Wednesday Shade's Children

Shade's Children The Violet Keystone

The Violet Keystone Abhorsen

Abhorsen The Monster

The Monster The Creature in the Case

The Creature in the Case To Hold the Bridge

To Hold the Bridge Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar

Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Above the Veil

Above the Veil Aenir

Aenir Mystery of the Golden Card

Mystery of the Golden Card Superior Saturday

Superior Saturday Sir Thursday

Sir Thursday Castle

Castle Lady Friday

Lady Friday Into Battle

Into Battle Dislocation Space

Dislocation Space Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1)

Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1) Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1

Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1 The Left-Handed Booksellers of London

The Left-Handed Booksellers of London Novel - A Confusion of Princes

Novel - A Confusion of Princes One Beastly Beast

One Beastly Beast A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3

A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3 Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2

Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2 Have Sword, Will Travel

Have Sword, Will Travel Fire Above, Fire Below

Fire Above, Fire Below Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case

Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case The Monster (Troubletwisters)

The Monster (Troubletwisters) Across the Wall

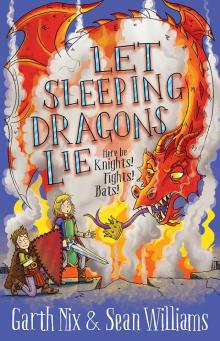

Across the Wall Let Sleeping Dragons Lie

Let Sleeping Dragons Lie![[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/abhorsen_03a_-_across_the_wall_preview.jpg) [Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall

[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall