Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Read online

Page 3

He looked outside.

Before him, buildings of stone stretched across a tan desert. Men and women clothed in headdresses and glittering jewelry bustled through a market square, a surprising number of cats weaving between their legs or lounging lazily in the setting sunlight. In the distance, a massive pyramid loomed.

So this was to be his next stop.

Gilgamesh smiled. One day, he would find someone to take his place—someone truly willing. In the meantime, he would make a difference.

He headed downstairs. After all, it was nearly dusk. Time for him to open up shop and see who stepped through the door.

Forest Law, Wild and True

Rachel Atwood

The fifteenth day June, in the seventeenth year of Our Reign:

Neither We nor Our Baliffs shall take, for Our castles or for any other work of Ours, wood which is not Ours, against the will of the owner of that Wood.

Magna Carta Clause #31.

~ ~ ~

All forests that have been made such in Our time shall forthwith be disafforested; and a similar course shall be followed with regard to riverbanks that have been placed in defense by Us in Our time.

Magna Carta Clause #47

~ ~ ~

“The Sheriff of Nottingham is taking wood from our forest!” Little John banged his wooden tankard against the rough table by the hearth in the public house at the edge of Windsor Village.

“Do we have title to the forest, or do we merely claim the land through centuries of common usage?” I asked. “To whom does the forest truly belong?” Damn all that legal training Tuck, or rather Abbot Mæson, force fed me. He made me question everything, including the foundation of a statement. Someday I would succeed him at Locksley Abbey in Nottinghamshire. Not soon I hoped.

I enjoyed my current apprenticeship at Windsor Castle as scribe to Archbishop Langdon. His Grace currently presided over meetings with King John and his Barons, drafting a peace treaty among them. So far, they addressed more pressing matters than the forest laws—like whether King John would be allowed to survive the signing of the treaty.

“Doesn’t the sheriff need the king’s permission to fell trees in a royal preserve?” Robin Goodfellow asked. He maintained his guise as a tall archer with no overlay of the ugly gnome that he sometimes used.

I was hard pressed to know for certain which was his original appearance.

“Sir Philip Marc wrote a petition to cut wood. I do not know if permission was granted,” I told my drinking companions.

“It is ours!” The tables shook as Little John pounded out his response.

“By who’s word, who’s law?” I asked again, in different words. “Why is it yours?”

“Don’t speak to me of your written laws. We are the forest folk, the Wild Folk. The woods were ours long before humans began taking our trees,” Robin Goodfellow said quietly. His human features slipped a bit, elongating his nose nearly to his chin and pointing his ears above his cocked hat. Then he shook himself and once more became human.

My ability to see their true selves was a gift from Elena, an ancient spirit who dwelled in a tiny three-faced pitcher. At first, I’d only seen beyond the obvious when I secreted her in my pocket. Now I need no longer carry the pitcher to have true sight. Little John, to those who knew him well, looked like a tall, well-muscled villein. Beneath this, I saw the forest giant clothed in leaves and twigs. Will Scarlett sang as sweetly as any bard or bird. The red feather in his cocked hat was the only token to his true avian heritage.

Father Tuck should have joined us for a tankard or two, but the Archbishop kept him close. Our good Abbot had not fled England seven years before along with the rest of the senior clergy when the Church in Rome broke with King John. Instead, Tuck, his youthful nickname, had taken up residence with the Woodwose—those who lived in the forest illegally—ministering to their needs as well as to the wild folk. He knew more about what England needed than King John, or Innocent III, the Holy Father in Rome.

I, Nicholas Withybeck, was an orphan; fetched up in the abbey at the age of three. Ten years later, in a moment of need, with the help of Elena, I had stumbled upon the Wild Folk one May Day. And now, in honor of their aide, I help them from time to time. This was one of those times.

My hand automatically went to the pocket in the front of my cowled habit, where once Elena’s gift had rested. It was a fleeting gift, for Elena gave nothing of permanence to anyone. The ancient pagan goddess of crossroads, cemeteries (the ultimate crossroad), and sorcery had taken herself and her three-faced pitcher back into the crypt of the abbey where she awaited the next young student willing to be guided by her wisdom and her laughter. There was emptiness in more than the pocket; my heart and my soul were yet to fully mend.

“The Sheriff of Nottingham has greater reasons than firewood,” Will said. He whistled a sprightly tune with hints of raucous laughter underneath the notes.

“And what might they be?” Little John demanded.

“To rob us of our home once and for all,” Robin replied. A sharp edge buried in the words, anger a hidden blade.

“His plans call for enough wood to heat his castle and repair the beams in his Hall three times over,” I grumbled. “His petition is tangled and obscure. It could mean many things. Or nothing at all. But he did request permission.”

“Human lies are given power when scrawled on parchment.” Robin growled out the words. He had no love of writing.

“True,” I said. “But there is more. What is his real reason? His darkest purpose?”

Little John snorted.

Robin held up a hand to quiet him.

I looked at each and finally Robin spoke.

“He still lusts after Herne’s water sprite Ardenia. He’ll destroy the entire forest to capture her spring.”

The words held anger deep and strong as only truth can. We all loved the gentle nurturing and healing powers of Ardenia’s spring. It nourished the forest. And all of those who lived there.

“Calm down.” The publican placed a heavy hand upon Robin’s shoulder, forcing him to remain seated.

“We’ll make certain he keeps his arrows in his quiver and his bow unstrung, Gilga,” Little John promised. “But pray bring us another round of ale.”

“Who’s paying?” the man who near equaled Little John in size asked. He looked me in the eye, as if he knew I was the only one of the group likely to have any coins.

I sighed. My debt to these folk came with many obligations. And of course I was the only one with coins. The others had no care of or need for money, except here at the Boar’s Head Inn. Gilgamesh often bartered ale for information, but not tonight apparently.

“So how do we stop Sir Philip Marc?” Will Scarlet asked as he held his tankard up for a pour from the freshly arrived pitcher.

I replenished his drink and moved on to the others.

“Can we inform the king of his perfidy?” Robin asked.

I choked on my laughter. King John had deeper problems than one patch of forest.

“First we’d have to catch the attention of His Highness,” I said. “Lately he listens to no one but Archbishop Langdon. He trusts no one but Langdon, and him only slightly.”

“Could his ear be bent by the words of Father Tuck?” asked Robin. “He has risen far in the church.”

I was about to form a protest when Gilgamesh caught my gaze and beckoned me to the bar.

I pushed my bench away from the rough table and approached the man of indeterminate years. He looked to be on the far side of forty but his eyes betrayed more experience than could be crammed into one lifetime. My special gifts told me to look deeply. Listen to the wisdom of the ages, Elena whispered to me, as she did from time to time, even though I no longer carried her with me.

“You heard her.” Gilgamesh fixed his gaze on me.

I gulped. He’d heard. No normal person could hear her unless he had carried the three-faced pitcher for a few years.

Both Elena and

Gilga laughed, hers high and gentle like tiny crystal bells, his deep-throated and rumbling akin to thunder right on top of us.

“Common Law is giving way to Written Law,” Gilgamesh said. Where had he learned such things? I knew about them because I’d studied them in various scriptoriums throughout England.

“I suspect this Charter that King John and Langdon discuss will become the foundation of a new way of thinking about the law,” I said. “It’s a way to bring peace among the Barons, the king, and the Church.”

Gilgamesh stared at me until I returned his glare. His brown eyes opened wide and I … fell.

New images streamed from his mind to mine. Signed documents. Men arguing in a gathering place assigned to them to form our laws. Men with the authority of the Crown and the community capturing law breakers. Twelve good men, honest and true, announcing a verdict …

I closed my eyes to break his contact with me.

“Enough,” I said. “I understand. I can see.”

“It will only be enough when you use the law to save the forest home of your friends,” Gilgamesh said in low solemn tones.

And I knew that I must somehow use the law to stop Sir Philip Marc, the Sheriff of Nottingham, from declaring his own laws. And I had to do it before he finished cutting every tree. I already composed in my head a letter to the Sheriff to cease cutting until the king had time to address his petition.

Would he obey a command signed by Abbott Mæson?

Who could enforce the written law when the Sheriff was supposed to be the king’s deputy?

As I asked myself these questions, Little John clutched his chest over his heart. His left arm hung limply. “He’s taken an ax to my tree,” he gasped. Not just any tree, John’s personal tree, the place from where he took his strength. A refuge when he tired of his human guise. The place from where he watched the world and watched over the humans he loved.

Gilgamesh filled a different pitcher, a small pewter one, with liquid from a tiny barrel in a back corner of his domain behind the bar. The aroma wafting through the pub reminded me of spring rain, summer flowers, crisp autumn apples, and the bite of the first winter snow.

I found myself plodding blindly in Gilgamesh’s wake as he marched over to the settle where my friends sat. He poured a measure appropriate to the customer’s size and need. Will received only a few drops, Robin about three fingers, and Little John a nearly full cup.

“Get him home, now,” Gilgamesh ordered the Wild Folk, as if one of them.

I held my own cup out for some. Gilgamesh surveyed me from toe to brow and back again. “I suppose you need a bit to do what you have to do.” He tilted the pitcher over my cup and transferred the feeble stream to me.

Hastily I tipped the cup up and spilled the special brew onto my tongue. The flavors burst free, flooding every surface and crevice with incredible sweetness that would put honey to shame. At the same time, it satisfied my craving for salt—like cheese but better.

I blinked in astonishment. Strangely I wanted no more of the brew. My mind cleared and I knew what I had to do and how to do it.

By the time I swallowed and nodded my appreciation to the publican, my friends had vanished, undoubtedly sharing with Little John bits and pieces of their travel magic to get them home in time to stop the Sheriff’s woodsmen. A tiny part of me pitied the axmen.

I ducked out of the pub and ran back to the castle. By the time I arrived the sun had set and the gates had been pulled closed. For me this was an inconvenience, not a challenge. I’d been sneaking in and out of locked and guarded buildings for as long as I could remember. Keeping the ramparts of the Keep to my left, I inched around the curtain wall, counting my steps.

One hundred paces. I knelt and ran my hand along the next to lowest line of building stones. The rough texture changed slightly. I found the deeper crevice where mortar had never been. A gentle push on one corner and the stone slid inward. At the same time, an almost invisible door—wooden panels cleverly painted to look exactly like stone—swung outward.

That was the last of the ease. I had to shove hard to move the door enough to squeeze my tall body through the opening. Then I had to move quickly before it swung shut again, silently. Clerics had been using this portal for generations and we knew how to hide our passage as well as keep it secret.

I emerged into darkness behind St. George’s church. I paused a moment to assess the shadows, considering what they might shelter.

“Returning a little late, aren’t you?” Abbot Mæson said flatly.

I knew that tone, meant to quail bold novitiates and arrogant students. I had faced it many times over the years.

“Our friends from Nottinghamshire needed my advice,” I replied, also keeping my tone even to hide the thick lump in my throat, fearing their demise if they could not counter the woodsmen before I could dispatch trusted knights to enforce the king’s law.

“What now?” The Abbot shifted in the gloom so that I could see he straightened from a lean against the back wall of the Lady Chapel.

I repeated our conversation verbatim as he’d trained me, stopping the narration when I had moved to the bar and talked to Gilgamesh.

“And what did the publican Gilga say to you?” His voice shifted to a note of humor. He sounded younger than his many obvious years, more like the Tuck who had wandered the forest with his great-grandfather Herne, the huntsman.

“We spoke of the nature of law.”

“Ah.” He scratched his chin.

I wished we could move into the torchlit courtyard so I could read his expression and posture as well as his voice.

“Come, we do not have much time. Tonight I am tasked with transcribing the final agreements into a fair hand to receive the king’s seal tomorrow on neutral ground at Runnymede.” He beckoned me toward the steps to the church sacristy.

My mind circled around the problem, finally settling on one issue. “Will the document be read aloud before the signing?” Or rather how many in the audience could read and not notice the insertion of an item or two? Or four?

Northumberland and his allies would not agree to any document that did not call for King John’s immediate arrest and execution—without the benefit of the trial outlined in the charter. Making the king subject to the law was not enough for them.

“Yes, someone appointed by Archbishop Langdon will read the entire document,” Tuck replied. “That should be me …”

“Or me.” The Northumberland alliance would not suspect me, a lowly novice and scribe, of adding things to the charter. I could alter a clause or two without rousing suspicion. Those who accepted the king’s seal would have to abide by the entire document.

I lit oil lamps and wax candles for better light while Tuck brought forth pages of notes and fine parchment. I blended ink and sharpened quills. I’d need many of them before the night was through.

By dawn I had written out, in a fair hand, the complete text that would become known as Magna Carta. With Tuck’s help, I managed to word the phrases innocuously enough that no one could object to them. And so they were read aloud the next day on the field of Runnymede, a boggy meadow between Windsor, the king’s bastion, and Staines, the encampment of his rebellious barons. Though we tried to limit the weapons carried onto the field, honor dictated that every knight and baron be allowed to carry his sword and dagger. William the Marshall would make certain that no weapon came within six feet of the king.

No matter how hot the tempers, this stretch of land on the banks of the River Thames was not big enough or stable enough to become a battlefield.

While Tuck read aloud the entire charter, I moved silently and unnoticed through the crowd. And so did many of the Wild Folk. Not the friends I had sent back to Nottinghamshire, but others who called the woods, the rivers and springs, and the broad meadows home. They came by the hundreds, in human guise. I pointed them toward those most likely to cause trouble. Every time a man touched his sword, one of the Wild Folk restrained his hand by gentle forc

e, a moment of confusion, and the hand would drop again.

And so, all the forests that had been reserved to the crown since the crowning of King John’s father, Henry II—the first of the Angevians—reverted to the original owners, and no one, not any of the barons, knights, foreign mercenaries, or even the king himself, could cut or burn the wood without their permission. The forest my friends called home reverted to Locksley Abbey. Sir Philip Marc, Sheriff of Nottingham, trespassed if he tried to cut any wood there, and Abbot Mæson of Locksley Abbey could bring down the wrath of the Church on any who so dared.

Sorting out the tangle of Forestry Laws and who had originally owned those lands, after so many decades, was a problem for later. I knew I’d be part of another charter designed specifically to protect the forests and the wild folk, but not today. The village of Woodwose—peopled by those who had no other home and thus lived illegally by their wits and the bounty of the forest—by custom owned their village as long as the Abbey ignored their presence. Little John’s tree was safe from the woodcutters.

The vision that Gilgamesh had granted me with his special ale had showed me that the forests would not last forever. Eventually, as England became more and more populous, people would till the land and take the forest. But not now. For now, Little John, Robin Goodfellow, Will Scarlet, and Father Tuck could live safely in their wooded home, and live on in the memories of those who came to love their freedoms as embodied in the great charter.

Historical Note: The document we call Magna Carta was renewed by King John’s son Henry III in 1216 after John’s death from dysentery. Some clauses were eliminated but the forestry references remained. Henry III reissued the document again in 1225 with a few more revisions. Alongside those revisions, he commissioned a special committee to map and document ownership of all the forests and set out new laws that applied to all of them uniformly. The Charter of the Forests has entered the historical record and become part of the British Constitution.

The Ragwitch

The Ragwitch Newt's Emerald

Newt's Emerald Grim Tuesday

Grim Tuesday Sabriel

Sabriel Mister Monday

Mister Monday The Missing

The Missing The Fall

The Fall A Confusion of Princes

A Confusion of Princes Troubletwisters

Troubletwisters Lirael

Lirael Lord Sunday

Lord Sunday Clariel

Clariel Drowned Wednesday

Drowned Wednesday Shade's Children

Shade's Children The Violet Keystone

The Violet Keystone Abhorsen

Abhorsen The Monster

The Monster The Creature in the Case

The Creature in the Case To Hold the Bridge

To Hold the Bridge Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar

Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Above the Veil

Above the Veil Aenir

Aenir Mystery of the Golden Card

Mystery of the Golden Card Superior Saturday

Superior Saturday Sir Thursday

Sir Thursday Castle

Castle Lady Friday

Lady Friday Into Battle

Into Battle Dislocation Space

Dislocation Space Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1)

Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1) Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1

Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1 The Left-Handed Booksellers of London

The Left-Handed Booksellers of London Novel - A Confusion of Princes

Novel - A Confusion of Princes One Beastly Beast

One Beastly Beast A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3

A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3 Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2

Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2 Have Sword, Will Travel

Have Sword, Will Travel Fire Above, Fire Below

Fire Above, Fire Below Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case

Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case The Monster (Troubletwisters)

The Monster (Troubletwisters) Across the Wall

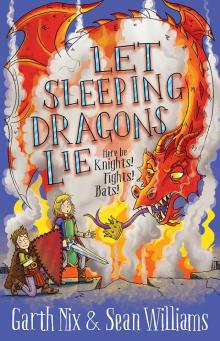

Across the Wall Let Sleeping Dragons Lie

Let Sleeping Dragons Lie![[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/abhorsen_03a_-_across_the_wall_preview.jpg) [Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall

[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall