Dislocation Space Read online

Page 3

She put the floorboards back and applied the knife to the white towels, cutting head holes in two of them. After a few minutes she had made a makeshift smock, and cut a number of strips to use as a belt and for head, foot and hand wrappings. In the snow outside, the makeshift white clothing would serve as camouflage.

Shortly thereafter, the Todesgeist of Stalingrad was loose in the camp.

As she’d expected given the lack of other prisoners, it was very quiet and there were no active patrols between the buildings, not even sentries pacing in frozen endurance outside any particular locations. She didn’t doubt the perimeter was guarded, and that the German dogs existed, but they were clearly not routinely let loose to roam. Only to pursue, when necessary.

It didn’t take her long to find the infirmary. It was the first large building in the direction the guard had glanced, and it was brightly lit. Aleksandra listened outside the door for a little while, then eased it open and crept into the vestibule. Crouched against the empty snow boot rack, she listened again, before easing open the inner door to look inside. A nurse was asleep in his chair, head down on the desk in front of him. Beyond the desk were six hospital beds in two rows of three.

Five beds were empty, the sixth was not.

Aleksandra crept close to the nurse, and sniffed. He smelt even more vodka-soaked than she did. One drawer in the desk was half open and, sure enough, there was a vodka bottle in it, with only a faint sheen of the spirit remaining inside.

She considered whether to kill him and stage it as an accident–maybe a drunken attempt to urinate outside in the snow gone wrong–but decided against it. She was a killer, sure enough, but only when it was absolutely necessary. For too long she had let the State determine whom she should kill, whether ordered by a superior officer or as at the last, by Stalin himself, the embodiment of all authority. Since she’d been in the camps Aleksandra had only killed when her survival depended upon it.

There was a slight movement in the sixth bed. She left the nurse and crossed the room, silent as ever. But not silent enough, it seemed. The heavily bandaged but curiously small figure in the bed spoke through the jagged hole of the cloth on its face, like some Egyptian mummy come to life. Aleksandra smelt burned flesh, the stench familiar from Stalingrad and many other places, the burned-out tanks of both sides in the long fight towards Berlin …

“Sashenka?”

The voice was a faint, cracked whisper, but Aleksandra knew who was in the bed.

“Yes, Vova,” she whispered, holding back a sob. She hadn’t cried for years, but now tears were close and had to be forced back. “How did you know—”

“I knew they’d bring you,” whispered Vladimir. “And who else would creep in here after midnight?”

In many ways, Vladimir had been Aleksandra’s second father. She had not seen him since a chance, brief meeting in East Prussia in late 1944.

“What have they done to you?”

The bandage-wrapped figure made a slight move, almost a shrug, and growled at the pain.

“This I did to myself,” he whispered. His voice rose and fell as he spoke through terrible pain. “Though I admit they gave me the opportunity. Listen.”

Aleksandra sat on the side of the bed, but was careful not to touch him or move the single gauze sheet that was laid across his bandaged body. His foreshortened body, because his legs had been amputated above the knee.

She knew the slightest touch would be agonizing for him, and turned her head aside so even her breath could not fall upon him.

“I had hoped I would … if not see you … speak to you before I die,” whispered Vladimir.

Aleksandra moved, just a little closer, but before she could say anything, he continued.

“Listen. They do not really know what has happened to me. The burns are only part of it. But you, my little Sashenka, you must use what I have learned.”

“Use?” whispered Aleksandra.

“Listen. Have you seen the Replica? Been in it?”

“Yes.”

“It was built based upon my exploration of what they call the Original. But I didn’t tell them everything. You can—”

“I can do nothing but what I am instructed,” said Aleksandra. “Shargei warned me. Again. If I do not comply, it is my parents they will punish, and Konstantin and Marie—”

She stopped. Vladimir was making a noise that was partway between an excruciating cough and a sob.

“What? What is it? Is there medicine I can—”

“No, no,” husked Vladimir. “I am sorry, so sorry, Sashenka. Your parents and the children … they are already dead.”

“But the photographs,” said Aleksandra slowly. “Shargei showed me … they are older, but…”

Her voice trailed away. They both knew what could be done to make photographs show what was wanted, not what was true. They sat in silence for a minute, before Aleksandra spoke again, her whispered voice like a knife slowly run along a sharpening steel.

“You are sure of this?”

“Yes,” groaned Vladimir. “It was only the day after … after you were taken. Boris Ivanovich Russov saw it done … from his attic window, he could look into the courtyard … he told me … I wrote to you, but…”

“Yes. I will kill them. All of them. All of them. Shargei first. And Stalin too.”

“Sashenka, Sashenka … you cannot kill them all … and to kill … like them … is to be … like them.”

He took a rasping breath to gather strength.

“There is a … better … better way. Listen.”

Aleksandra bent close enough that she could feel the faint waft of his breath as he whispered, the awful stench of his burned flesh so strong in her nose and throat. He spoke with both difficulty and urgency, as if he had waited almost too long to impart the information he wanted to share. He made her repeat what he had told her, to be sure it was fixed in her mind. Then he sighed. Aleksandra was afraid he had died in that moment, till he took in another raspingly slow, painful breath.

“Aleksandra. There is something more … I ask you … you must help me to … to make my escape.”

“Yes.”

“You have the … extra inch of height … and my knowledge. You will make it. I should not … have turned back. It would have been … been better to … die inside than here.”

“Sssh,” soothed Aleksandra. “Where is … ah!”

She spotted the drug cabinet, walked to it, and picked the lock in less than a minute.

The first vial of morphine seemed to hardly affect Vladimir at all. She injected another, into his neck. His breathing grew more ragged, and he made a rhythmic, slow sound in his throat like a drain unblocking.

The third vial did the job. Aleksandra waited by his side until she was absolutely sure he was dead, and then took the empty vials and the metal syringe and put them on the desk by the nurse’s hand. Waking from his alcoholic stupor the man might think he had somehow administered the overdose, and would be frightened enough to hide the evidence. Or he would be found like this, and blamed. Either way worked for Aleksandra.

Back in her hut, she slowly burned the towels in the iron stove, then went to bed. But she did not sleep. She lay there, thinking, going over what Vladimir had told her. Remembering the directions, the technical suggestions, the timing.

And she thought of her family, dead for so long. The day after she had been arrested. All that time … Aleksandra had always feared they had been executed or sent to the camps, but she had forced the suspicion aside. Their continued existence in the everyday world had been something to live for.

A treasured delusion.

No more.

There was no commotion in the camp the next morning. No obvious signs that Vladimir had been found dead, or that he had been there at all. Guards came for Aleksandra, escorted her to breakfast, escorted her to the Replica where Termin was waiting by himself, without Shargei. She was given a skin-tight suit to keep her warm–Termin said it was the kind th

at divers wore–made from a rubber-like fabric that was not rubber. Someone had removed the main label, but there was printing inside the leg that said it was made in America.

Aleksandra was sent into the strange cork-lined steel tunnel again, encouraged to go as far as she could, to go as fast as she could, to remember the intersections and turns and risers and down-shafts.

Shargei was there when she came back out. Neither he nor Termin explained anything, nor would they answer any of her questions about the Replica, or the Original it modeled, or anything else.

Not that Aleksandra needed them answered. Vladimir had given her the key points, at least as he understood them. Which was likely more than either Shargei or Termin knew. After all, they had never been inside the Original.

Then there was the sauna again, but only a half-bottle of vodka, and dinner served in her hut. Aleksandra left the floorboards in place, and did not creep out for nocturnal roaming.

This was the pattern of her days, for a week. Practice in the Replica. Recover from practice. That was all.

* * *

On the morning of the seventh day, the guards escorted her a different way through the camp, to the northern side she had not seen. There was another, internal compound there, a small area surrounded by concertina wire three coils deep and stacked six coils high on special pickets. It had a double gate, manned by four guards. There was an odd, wooden tower in the middle of this compound, a rectangular edifice like a tall, very narrow church, with a high-peaked roof. Or perhaps a bizarre, over-sized grandfather clock case.

Shargei and Termin were waiting outside the door to this thin building, which on closer inspection reminded Aleksandra very much of a four-storey outhouse. It wasn’t big enough to fit more than a couple of people inside, standing up. The door had an enormous bolt on it, and a very large padlock, an American Lockwood which Aleksandra knew she could not easily pick. Not that she needed to, since Shargei had already put the key in the padlock, though he had yet to turn it.

“We are sending you into the Original today,” said Shargei. “The entrance lies behind this door. I remind you that the existence of this … anomaly … is most secret and is not to be discussed, even with others at this camp.”

“Anomaly?” asked Aleksandra. She kept her face still, revealing nothing of what she knew, or suspected, or feared.

“It is a tunnel, of sorts,” said Termin enthusiastically. “An inter-dimensional tunnel.”

“Show me,” said Aleksandra.

Shargei looked at his watch.

“In two minutes,” he said. “We must wait for the orange light phase.”

“We don’t understand the nature of the tunnel, or its composition,” Termin rushed along, waving his hands. “Its walls are coherent energy that behaves as mass or imitates it, yet it has additional characteristics, visible states, indicated by light. It cycles through these states from red to violet, the spectrum visible to the human eye, which is doubtless no coincidence. But the red state at the beginning is very dangerous, a lethal form of … of radiation, as is the violet at the end—”

“The sixteen-minute deadline in the Replica,” said Aleksandra. “That relates to this cycle? And the junctions are safe?”

Shargei smiled coldly.

“No,” he said. “The junctions are not safe. But the rate of progress necessary to get from the entrance to what we believe is an exit to another world requires you to reach Junction A in sixteen minutes from the end of the Red phase, during the Orange period. The phases inside the Original are each of twenty minutes’ duration, or to be exact, nineteen minutes and fifty-eight seconds. You must get to the known exit at the end of the tunnel within thirty-five minutes, make an investigation of no longer than ten minutes and return within thirty-five minutes, before the Violet phase begins. From the times you have managed in the Replica, this should be achievable for you.”

“What’s at this other exit?” asked Aleksandra.

“Another world!” exclaimed Termin, throwing his hands up in excitement. “Think of that!”

“How do you know?”

“The operative who mapped the Original saw a sky and felt the breeze from the other exit, though he could not manage to climb out into it. You did, in the Replica.”

“What if I can’t get back?” asked Aleksandra. “I might get killed by something in this ‘other world’. Or what if I’m too slow and the Violet phase–whatever that is–gets me.”

“If you allow that to happen, then your family will suffer the consequences,” said Shargei. “But if you do well, they will prosper. It is your—”

Aleksandra pivoted on her heel and sliced the throat of the closest guard with her saw-blade knife, blood spraying in a high arc across Termin. As the guard clutched at his throat, gargling, she snatched his PPSh-41 submachine gun, cocked it and fired one swift, sweeping burst, killing the other three guards. She swung the weapon back on Shargei as he scrabbled at his pistol holster and emptied the drum into his head, catapulting him against the door of the narrow building. He rebounded off it and slid to the ground, essentially decapitated.

Termin made a pathetic, mewling noise.

Aleksandra ignored him. She threw down the PPSh-41 and picked up her knife, tucking it back behind her ear. She turned the key in the padlock, snapped it open and slipped it out of the catch.

Behind her, a siren sounded, a call to action. Quicker than she’d thought. Gunshots must not be as common here as in other camps. It was followed a moment later by distant shouts, and the baying of dogs.

Termin continued his strange mewling noise.

“Shut up!” barked Aleksandra. “I’m not going to kill you.”

The Academician choked, coughed and managed to splutter out, “Why? They will kill your family—”

“They’re already dead,” said Aleksandra bleakly. “Yours too, probably. Is it safe to open?”

Termin looked at his watch and nodded.

She opened the door, blinking at the bizarre sight of a tunnel made of luminous orange … orange air … suspended in the air at head height, extending through the back of the building as if the wooden wall didn’t exist. Though she knew from the Replica the tunnel only extended several metres before turning, it looked as if it went on forever, straight as a die.

She dragged Shargei’s body over, took off his Rolex and strapped it on her ankle, then stood on his chest, to make it easier to haul herself up into the tunnel entrance.

The shouting was getting closer, and the sound of the dogs.

“Y-y-ou’re … g-g-oing through?” stuttered Termin.

“Obviously,” said Aleksandra. She pushed up on her toes and threw herself up and into the tunnel, at the same time slipping her left arm out of its socket so she would not get stuck.

“If you come back, and tell me … tell us … I think … I think … you’d be forgiven,” shouted Termin, his voice desperate. “I’m sure!”

His voice was drowned out by a sudden growling and barking and Termin’s voice rose an octave.

“No! No! Not me! It was her—”

Aleksandra undulated easily forward. The sides of the tunnel did flex under her skin, a little, and felt like nothing she had ever moved through before. Not cloth, or timber, or metal. The description of “velvet” was close, but still not right. And there was a faint sensation, like static electricity, a mild discomfort where her skin touched the tunnel.

The sweeping left turn was no problem. Aleksandra didn’t even need to dislocate her right shoulder. The corkscrew turns were a challenge, but no more difficult than in the Replica, though she was glad of the daily back bends and contortion rolls she had done at the camp, keeping her spine supple.

The right and immediate left turn was difficult. Even with both shoulders dislocated, Aleksandra felt herself beginning to stick and slow down. The weird orange surface wasn’t the same as the cork-lined steel. For a moment she felt a tinge of panic, but she forced it away and managed to continue on, to Junct

ion A and beyond.

She couldn’t help thinking about what Vladimir had said the Red or the Violet light could do. He had only been a few seconds too slow, his lower body still in the Original as he struggled to get out. But that had been enough. His legs had been cooked from the bones outward, requiring immediate amputation, and his upper body–even though out of the tunnel–had suffered something similar to the flash burns they both knew from the war.

Aleksandra forced those thoughts away, to concentrate on her progress. From Junction A it was easy going for a while, until she came to a series of very close right-angle turns that required her to bend at maximum extension from neck and waist, in opposite directions.

Halfway through, Aleksandra got stuck.

She couldn’t move forward or back, she needed just a few millimetres more behind her shoulders and under her hips, and that space wasn’t there.

The panic came back, and again she forced it away. She thought about the other things Vladimir had told her, and simply waited, slowing her breathing, letting her mind and body relax.

After a long minute, perhaps two, the deep, solid light all around her suddenly changed from orange to yellow, and the sensation of static electricity disappeared. The tunnel was suddenly warm now, the luminous, otherworldly surfaces felt like a stone floor warmed by summer sun.

There was also now more flex in the tunnel. The material gave way far more than in the Orange phase, much more than the thick cork lining of the Replica.

But even with the extra flex, Aleksandra only managed to wriggle and writhe forward five or six centimetres before she ran into the section where the tunnel ahead turned back on itself. It had been almost impossible in the Replica, and she had gouged the cork lining there. It would be actually impossible here unless something else Vladimir told her was true.

“Oh Vova,” whispered Aleksandra, and though she had not believed in God for many years, she uttered a short prayer that her mentor had not confused the extraordinary reality of the Original with morphine hallucinations.

The Ragwitch

The Ragwitch Newt's Emerald

Newt's Emerald Grim Tuesday

Grim Tuesday Sabriel

Sabriel Mister Monday

Mister Monday The Missing

The Missing The Fall

The Fall A Confusion of Princes

A Confusion of Princes Troubletwisters

Troubletwisters Lirael

Lirael Lord Sunday

Lord Sunday Clariel

Clariel Drowned Wednesday

Drowned Wednesday Shade's Children

Shade's Children The Violet Keystone

The Violet Keystone Abhorsen

Abhorsen The Monster

The Monster The Creature in the Case

The Creature in the Case To Hold the Bridge

To Hold the Bridge Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar

Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Above the Veil

Above the Veil Aenir

Aenir Mystery of the Golden Card

Mystery of the Golden Card Superior Saturday

Superior Saturday Sir Thursday

Sir Thursday Castle

Castle Lady Friday

Lady Friday Into Battle

Into Battle Dislocation Space

Dislocation Space Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1)

Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1) Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1

Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1 The Left-Handed Booksellers of London

The Left-Handed Booksellers of London Novel - A Confusion of Princes

Novel - A Confusion of Princes One Beastly Beast

One Beastly Beast A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3

A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3 Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2

Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2 Have Sword, Will Travel

Have Sword, Will Travel Fire Above, Fire Below

Fire Above, Fire Below Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case

Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case The Monster (Troubletwisters)

The Monster (Troubletwisters) Across the Wall

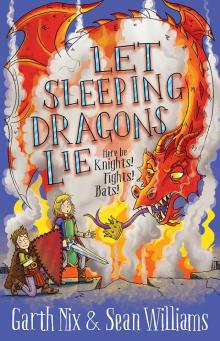

Across the Wall Let Sleeping Dragons Lie

Let Sleeping Dragons Lie![[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/abhorsen_03a_-_across_the_wall_preview.jpg) [Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall

[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall