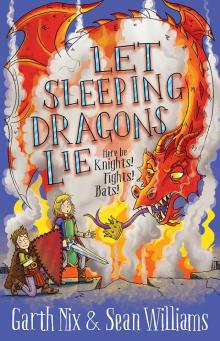

Let Sleeping Dragons Lie Read online

Page 5

‘Do you think they’ll recognise us?’ she whispered to Runnel.

‘Unlikely,’ said the sword, her voice slightly muffled by the saddle blanket. ‘Even if they’ve been alerted about the king, they’ll be looking for an older couple on foot, not what looks like a family group on horseback.’

‘Oh, I hadn’t thought of that.’ Still, she sat ready in her saddle as the guards approached, pikes held at an angle so they crossed, blocking the way.

Egda started telling the guards the story about heading for Winterset to establish his grandchildren in their proper trades, but he told it in a voice that was much lighter and higher-pitched than his own, and included so many unnecessary details – the weather they’d supposedly left, the meals they’d eaten on the way, what people had told them about the road ahead – that the guards soon became restless.

‘Cease this blathering, Engelbert,’ said Hundred in a crone’s harsh snap. ‘Give these good men the toll and we’ll be on our way.’

Making a show of unhappiness, Egda reached into his saddlebag for a purse. Then, with great reluctance, he proffered each guard a silver penny. They snatched the coins and waved the party on.

‘Never fails,’ said Hundred once the guards were out of earshot. ‘One good thing about getting old is that nobody takes you seriously anymore.’

‘Same with being young,’ Eleanor said.

‘True enough.’ The old warrior turned in her saddle to look at Eleanor and, to Eleanor’s utter surprise, winked.

Keeping a close eye on the town’s inhabitants, they proceeded along Ablerhyll’s crowded main thoroughfare, Hundred in the lead and Odo bringing up the rear. He kept his horses on a tight rein, wary of slippery mud and loud noises that might see him unseated. The horses were calmer than he was, well used to people and their activities. His anxious gaze soaked up tradespeople hard at work, children playing, stray dogs running between them, and rats eking what living they could from the scraps. There were tiny flies in abundance, and over all a fug that reminded him of his crowded home after a long winter. Through a constant rabble of voices, he could make out what sounded like dozens of cracked bells ringing in the distance.

They passed a market, and the smell of mutton pies made Eleanor’s mouth water. She yearned to stop and try one, but there was no room in their mission for dallying. Maybe later, she told herself. When they had defeated the regent, there would be time to eat all the pies she wanted …

‘Something is not quite right,’ warned Egda.

Odo nodded. He felt it too. Ever since entering the town, his hackles had been raised, like someone was watching him behind his back. He turned his head both ways, but couldn’t see anyone acting out of the ordinary. No one was looking at them at all, as far as he could tell.

‘You are perilously exposed,’ said Biter, the tip of his pommel poking out into view. ‘I do not like it. An assassin could easily reach your position with a blade thrown from an open window, or from a nearby rooftop with an arrow, or even a dart tipped with aetrenbite poison—’

‘Be quiet, little brother,’ said Runnel. ‘You will give us away.’

Biter subsided, grumbling.

Eleanor looked around her, eyes and ears alert.

‘Birds,’ she said. ‘I can’t hear any.’

‘Ah, yes,’ said Egda. ‘There should be pigeons, sparrows, all the winged scavengers. But the sky is silent.’

‘Otto and Ethel, look up at the tops of those spires, but carefully, so you won’t be noticed,’ Hundred instructed.

Odo scratched his head and glanced up under cover of his hand.

Perched on the very top of the nearest spire was the largest raven he had ever seen, head crouched low into its feathery blue-black shoulders.

Its gleaming eyes turned to follow them.

Odo glanced to another spire, and another. Each had its raven, and each raven was watching them with a soundless, chilling intensity.

A slight movement caught his eye. There was another raven, much closer, perched atop an eel-seller’s stall. It met Odo’s gaze, and he saw with a shudder that its eyes were not the normal black of a raven’s, but a smoky grey.

Eleanor saw it too.

‘The person who sent the bilewolves …’

‘Yes,’ said Hundred. ‘Somewhere, a craft-fire is burning.’

‘How do they know we’re here?’

‘They may not. They may simply be watching every traveller on this road.’

‘So what do we do about them?’ asked Eleanor. ‘Go inside where they can’t see us?’

‘No,’ said Egda. ‘We must not be trapped here. The best way to avoid an ambush is to move fast, before the jaws can close.’

Eleanor wished he had chosen a different metaphor. The poisonous ferocity of the bilewolves was still fresh in her mind.

‘We just keep going?’ she asked. ‘And hope nothing gives us away?’

‘Precisely,’ said Hundred. ‘The road is open ahead. Let’s trot. That should not be too suspicious. Simply travellers anxious to make the most of their time.’

Eleanor nudged her mount with her knees, and the horse obligingly broke into a trot. Eleanor grimaced as she lifted herself off the saddle in time with the rhythm. The clip-clop of the horse’s hooves made a martial drumbeat on the cobbles. Odo fought the urge to look at the birds and concentrated instead on making himself as inconspicuous as possible. He tried whistling nonchalantly, but that only made the lack of birdsong even more obvious. Everyone seemed to be looking at them now, through barred windows or over half-empty barrels, around companions or across tables strewn with wares. With every minute, Odo felt the tension in the small of his back grow.

Finally, when he felt he could take no more, he caught a glimpse of the gate on the far side of the city through a gap between two tall houses whose upper balconies overhung the road. It was so close, just around one more corner and then straight. He felt a surge of relief.

Hundred saw the gate too, but also something else. She raised her hand and everyone reined their mounts back to a walk. They clustered together as they slowly continued.

‘The gate is closed,’ she said quietly. ‘It shouldn’t be closed during the day.’

‘Show no alarm,’ said Egda. ‘When we turn the corner, we’ll come to a stop. Odo, act as if your horse has taken a stone in its shoe, while Hundred looks to see what is going on at the gate.’

‘What if it’s closed to keep us in?’ asked Eleanor.

‘They have no reason to suspect—’ began Hundred.

But she was suddenly interrupted by a loud voice from behind them.

‘Sir Odo! Sir Eleanor! Stop!’

Eleanor’s right hand lunged down the flank of her horse. Runnel was already moving. Barely had the sharkskin grip touched the palm of her hand than she was wheeling around, sword upraised and ready, Odo matching her speed precisely. Runnel and Biter caught the light brilliantly, sweeping forward and down to point at the throat of a man running full tilt towards them.

The man gulped and skidded to a halt just out of reach of the deadly steel. He was old and muscular, with wild, white hair sticking out in odd tufts from under an acorn hat. He stopped so suddenly his hat tipped off and landed in the dirt at his feet. He went to pick it up, then froze as Biter twitched warningly.

‘It’s me!’ the man cried. ‘Old Ryce. Surprise!’

Odo squinted. It was true. The last time he had seen the ancient machinist – who had been held captive by the false knight Sir Saskia and made to fake a dragon’s fire – Old Ryce had been a filthy, ragged figure hurrying up the river road for places unknown. Now he was clean, dressed in a smock covered in pockets, and wearing a new hat. Which was getting muddy on the road.

‘Oh, sorry,’ said Odo, withdrawing Biter. ‘I didn’t recognise you.’

‘What are you doing here?’ asked Eleanor.

‘Oh, you know Old Ryce. Working, building – no dragons this time. Never again!’

‘You are

certain you know this man?’ asked Hundred, two jagged throwing knives held at the ready. ‘He has the look of someone who has experienced evil.’

‘We definitely know him – and yes, he has,’ said Eleanor, face pink at the thought of how close she had come to skewering their old friend. ‘We rescued him from a false knight and he helped us survive a terrible flood.’

‘Old Ryce is very glad he did too,’ stammered the old man. ‘That’s my name, and good friends we all are. Hello, Sir Eleanor and Sir Odo! I saw you but you were moving so quickly I almost missed you, Your Honours. But I didn’t, did I?’

‘Indeed, you did not,’ said Egda. ‘However, perhaps now is not the best time for a reunion.’

With a furious squawking and flapping of wings, a dozen black shapes converged on them from all sides, claws and beaks reaching for their eyes. Odo ducked and covered his head with one arm. Eleanor lunged her horse forward, out of the cloud of birds. Egda spun his staff overhead, knocking a raven to the ground. Hundred produced a whip and cracked it twice. Three birds fell dead, instantly slain.

That left eight, climbing up to regroup before they dived again.

‘We are too exposed here,’ Hundred said. ‘More will come!’

None of the birds had attacked Old Ryce, who stood stock-still with his mouth open, dumbfounded. At Hundred’s words, he woke from his shock.

‘This way! Old Ryce knows where the birds won’t go.’

He headed off down a narrow side alley at a surprising clip, all elbows and smock flapping around his knees. The others dismounted swiftly, leading their horses. Odo was the first to follow, almost dragging his horse along. She was a headstrong bay with the name ‘Wiggy’ branded into her halter. Where she went, the others would come too – and they did, down the narrow, washing-draped lane, the rapid chatter of their hooves echoing from all sides.

Eleanor peered up, keeping a sharp eye for the birds. The ravens tracked the fleeing party in a ragged flock from above, occasionally ducking lower to see their quarry through obstructions and cawing for the others to catch up.

Old Ryce took a series of tight turns deep into the warren of Ablerhyll, the alley darkening as the upper levels of the houses grew closer and closer together, blocking out the sky. Occasionally one of the people or a horse slipped in the muck underfoot, but none of them fell, and even as the smell of filth and refuse rose up to choke them, the birds became scarcer, unable to get through the overhanging rooftops, upper storeys, washing lines, and bird nets hung by pigeon hunters.

‘This way,’ called Old Ryce over his bony shoulder. ‘Nearly there!’

Through the narrowest of gaps between two lurching, irregular balconies that almost met above his head, Odo caught sight of the spire with the strange windmill. The blades were turning sluggishly in a faint wind, each lined with metal chimes, so the entire construction made a constant racket as it rotated, the same racket that Odo had noted earlier. The birds that hadn’t been put off yet were scattered for good now, retreating with a series of indignant cries from the incessant metallic noise and the four giant blades threatening to smash them into a cloud of feathers.

‘Through here,’ said Old Ryce, opening a large double door at the rear of the structure and waving them inside. Once they were all under cover, he dropped a bar down to seal the doors with an echoing slam.

The base of the spire was as big as a barn, with a high, arched ceiling and walls covered in mysterious pipes and gears leading up into the shadows. Over the sound of the chimes came a steady, mechanical clanking and gurgling. The horses whinnied nervously, and Eleanor sheathed Runnel in order to soothe hers by patting it on the neck as she caught her breath.

Egda’s expression was pained, the sounds clearly an affront to his sensitive hearing. ‘What is this cacophonous place?’

‘Ah! This is the answer to Sir Eleanor’s question. What is Old Ryce doing here? Well, when he was released by the real dragon, who thankfully didn’t take offence at the making of a fake one, he didn’t know where to go, so he went where things needed fixing. First an axle on a wagon that broke in a ditch. Then a waterwheel with a wobble. Then a village clock that was stuck at midnight. Finally, this. Honest work!’ ‘I don’t doubt it,’ said Hundred, dismounting, closely followed by the others. ‘But what is it?’

‘A backwards weather vane, Your Honour. Ain’t it marvellous?’

‘A weather vane that runs backwards?’ asked Odo. ‘What for?’

‘Good question. You really ought to ask the clever chap who built it, only he’s dead now. No one really knows how that happened – they found his shoes in a mud puddle in the cellar but nothing else – or understands the machine, but I can fix what seems to be broken. Indeed, I think I have fixed it, at long last. Funny how things don’t seem to stay fixed around here. But all Old Ryce has to do now is pull the lever and see if it works.’

‘How will you know?’

‘It’ll rain. That’s what it does. It brings rain to wash out the streets and feed the farms … and whatever else rain does.’

Eleanor understood then. Ordinary weather vanes measured the weather. A backwards weather vane created the weather. Remembering the dry fields on the way to Ablerhyll, she could well understand why the town would want one.

‘Such devices were known of old,’ said Egda heavily. ‘But they were prohibited, with good reason. Interfering with weather is all too like the craft-workers who twist and change good animals into beasts like bilewolves.’

‘The Instrument hired me himself,’ said Old Ryce nervously. ‘Have I done wrong? Old Ryce means no harm, but if this is like that dragon engine—’

‘Let us not be distracted by talk of the device,’ interrupted Hundred. ‘We are now trapped. How are we to escape Ablerhyll with ten horses in tow? We cannot leave them behind. We need them to get to the capital quickly.’

‘We are safe here for the moment,’ observed Runnel. ‘The birds cannot get in.’

‘The fiend who lit the craft-fire will be seeking other beasts even as we speak,’ said Biter. ‘One of us should go on a sortie to seek the smoke and deal with him once and for all.’

‘Craft-fires don’t smoke – it all goes into the creatures they control,’ said Hundred. ‘But a sortie, all of us riding out at once, might work, if the gate is opened by someone first. I can sneak – wait, what’s that?’

Over the ringing of the chimes and the clanking of the backwards weather vane, they heard one dog howl, then another. Soon a whole pack was raising up an unnatural chorus.

‘From birds to dogs,’ said Hundred grimly. ‘Even if the birds have lost us, the dogs will sniff us out.’

‘We can fight them off,’ said Eleanor. ‘Old Ryce, do you have any weapons?’

The old man looked fearfully around. ‘Just tools. And my lunch, Your Honours. But I want to help …’

‘If we’re going to make a stand here,’ said Odo, ‘it’d be better if you got out while you still can. This isn’t your fight.’

‘Old Ryce has to help his friends. That’s what friends do. Particularly when it’s his fault they found you.’

‘It’s not your fault,’ Eleanor said. ‘It’s not Odo and me they’re looking for. You just got caught up in this by accident.’

‘Indeed, and I will not have another innocent life on my conscience,’ said Egda. ‘Old Ryce, in the name of the authority I once bore, I command you to leave immediately.’

‘Authority?’ echoed Old Ryce, blinking at Egda. ‘Command? Oh my, that nose … I thought I recognised it, but never dreamed …’

He went down on both knees, joints cracking loudly, and prostrated himself.

‘Get up and run, man,’ said Hundred. ‘Before it’s too late!’

Outside, the dogs fell silent, only to be followed a moment later by a heavy pounding on the huge doors.

‘Open! Open!’ boomed a voice. ‘By order of Instrument Umblewit!’

‘Oh dear,’ said Old Ryce, raising his eyes.

&n

bsp; ‘Get rid of them,’ Hundred hissed. Old Ryce nodded and went to the gate, putting his head close to the bar.

‘G-go away!’ he shouted. ‘I’m busy!’

‘Too busy for Instrument Umblewit? Don’t forget who pays you, tinkerer.’

‘Um, Old Ryce is conducting a dangerous experiment. Oh, yes, very dangerous!’

‘It’ll be very dangerous for you if you don’t let us in right now,’ came the retort, followed by renewed pounding. Fortunately, the doors were extremely solid and sounded as though they could take anything short of a battering ram.

‘What can we do?’ asked Eleanor. ‘We can’t fight the entire town, can we?’

‘We can fight our way through,’ said Hundred, testing her sword’s edge with one thumb.

‘Why don’t we try to talk to them?’ Odo asked, seeking another way. They had barely begun their mission and here they were facing certain death at the hands of the Instrument and his minions! ‘They’re not really going to attack two knights, are they?’

‘They will once they see us,’ said Hundred. ‘I am sure the orders have gone out to kill anyone who happens to be blind and has an impressive nose.’

Egda’s expression soured at that description, but he said nothing to contradict it.

‘There has to be something we can do,’ said Eleanor, gripping Runnel tightly in frustration.

‘There is a way out,’ said a pale-skinned, child-sized figure that stepped out of the deepest shadows, flanked by two just like it, but taller. It had green hair the colour of an old bottle, and skin so thin that silvery veins could be seen pulsing beneath. Long fingernails tapped a stone-encrusted belt keeping its dark smock clinched about its waist. Black eyes regarded them with wary and not entirely welcoming calm.

‘Urthkin!’ barked Biter, jerking into a guard position.

‘Where did you come from?’ asked Odo, tugging his sword back down to his side. They had met these underground creatures before, and he remembered very well how dangerous they could be if provoked.

The Ragwitch

The Ragwitch Newt's Emerald

Newt's Emerald Grim Tuesday

Grim Tuesday Sabriel

Sabriel Mister Monday

Mister Monday The Missing

The Missing The Fall

The Fall A Confusion of Princes

A Confusion of Princes Troubletwisters

Troubletwisters Lirael

Lirael Lord Sunday

Lord Sunday Clariel

Clariel Drowned Wednesday

Drowned Wednesday Shade's Children

Shade's Children The Violet Keystone

The Violet Keystone Abhorsen

Abhorsen The Monster

The Monster The Creature in the Case

The Creature in the Case To Hold the Bridge

To Hold the Bridge Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar

Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Above the Veil

Above the Veil Aenir

Aenir Mystery of the Golden Card

Mystery of the Golden Card Superior Saturday

Superior Saturday Sir Thursday

Sir Thursday Castle

Castle Lady Friday

Lady Friday Into Battle

Into Battle Dislocation Space

Dislocation Space Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1)

Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1) Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1

Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1 The Left-Handed Booksellers of London

The Left-Handed Booksellers of London Novel - A Confusion of Princes

Novel - A Confusion of Princes One Beastly Beast

One Beastly Beast A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3

A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3 Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2

Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2 Have Sword, Will Travel

Have Sword, Will Travel Fire Above, Fire Below

Fire Above, Fire Below Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case

Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case The Monster (Troubletwisters)

The Monster (Troubletwisters) Across the Wall

Across the Wall Let Sleeping Dragons Lie

Let Sleeping Dragons Lie![[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/abhorsen_03a_-_across_the_wall_preview.jpg) [Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall

[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall