Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Read online

Page 5

Later the same day, Wat Miller came by the forge with a knife Gil wanted sharpening and Da sent Mared’s brothers out of the forge to watch the goat at her grazing. Mared made to take ale to the men and Mam called her back sharply; that too was strange. And then, Wat left without stopping to greet Mam. He’d had a basket with him when he came, but leaving he carried only the knife, wrapped in a cloth. “Wat’s left his basket,” Mared said to Mam. “Shall I run after him with it?”

But, “Wat’s old enough to look after himself,” said Mam. “Get on with your spinning.”

That night Da told the children that the forge was out of bounds to them for now. “I’ve a commission for a merchant over to Rhiw Fabon and it’s delicate work. I don’t want any accidents.” The eldest of Mared’s brothers grumbled a little at that, considering himself slighted, but Da would not be swayed and Mam spoke sharply to all of them.

Her brothers were all still young enough to regard their parents’ words as law, but Mared at twelve was almost a woman grown and old enough to know when there was something hidden. That night, a rattling by the hearth woke Mared. She peered out from under her blanket to see Da, fully dressed, holding the close-lantern in his hand. He glanced once about the room and Mared hastily shut her eyes. A moment later, she heard the door creak open and then close. She counted slowly to ten under her breath, then crept out of bed. She took her shoes in her hand and Nain’s old scarf for a wrap, and slipped to the door. Was Da going to the forge? She put her eye to the latch-hole and peered out. No, instead, he crossed the yard and headed out the gate and the track towards the village. Mared waited until he was out of sight round the first bend, then slid quietly outside herself. A frost had come down and the hard earth was chill under her feet. Hastily, she tugged her shoes on, then set out after Da. The sky was clear and a thin slice of moon provided enough light to see by. At this hour, the gate would be closed: where could Da be going? She ran until she could see Da again, then followed him at a careful distance.

As he neared the village, he turned right, away from the gate. Was he going to the mill? It seemed a strange hour for that. But he passed that turn, too, and instead carried on along the line of the wall towards the river. But just before it came into sight, he stopped and looked around him. Mared ducked behind a bush and held her breath. Da moved a square rock to one side, then knocked twice on the ground—at least, that was what it looked like—and then a beam of light sprang up at his feet.

The king under the hill … For a moment, Mared was inside one of Nain’s stories. Then she realized it was a trap-door of some kind. Da bent down and disappeared though it. The light vanished as the door shut behind him. Again, she hesitated. Then, once she was fairly sure no-one was watching, she crept after him.

The trap-door was closed and barred from within, and there was no latch string, but a faint line of light rimmed it and there were a few cracks in the wood here and there. Mared peered through one of them. She could see stone flags and the edge of what looked like a barrel. A tall figure stood near the door. It was far too tall to be Da: the figure shifted and she caught a glimpse of a hand. It was Gil; this must be the cellar of the inn. Gil was talking, something about old laws. Mared bent closer and her elbow knocked against the wood.

She whirled, ready to run, but behind the trap door clunked open. A heavy hand came down on her ankle and she gasped. A voice—Gil’s—said, “Now then, Mared, no need for panic. Turn round, now, and tell me what you’re doing here.”

“I …” Mared stammered.

“Better you come inside.” Gil reached up his arms to her.

She could hear Da behind him, sounding cross. She was in so much trouble now; it would only get worse if she ran. Mared slipped down through the trap door. Gil caught her, set her gently on her feet.

He looked down on her from his great height. King Bran himself could not have seemed taller in that moment. The shadows themselves appeared to drape themselves around him like a nobleman’s robe. Mared made to speak and he put a finger to his lips. Then he drew her after him, toward the main part of the cellar where Da stood, frowning. His face promised consequences later.

Gil said, “Don’t scold her, Iestyn. She’s a bright girl and she’s helped us already by carrying my message.”

“We’ll see,” Da said, but the frown faded.

Gil nodded, then went on, “All’s well. It’s just the smith’s daughter.”

“Mared,” a new voice said, and a new figure formed out of the darkness. Old Wyn. But if Gil looked more like Bran than his familiar self, then Old Wyn was even stranger. His gray hair was combed back off his face and tied with a leather thong: in place of his familiar woollen tunic, he wore a shirt of mail, every bit as fine as that worn by the bishop’s brother, who stood higher in England even than the earl, and who Mared had seen once when she was a small girl visiting Penwern with Da. Old Wyn came forward into the light shed through the door and smiled at her. “I remember her well. You were a babe in your mother’s arms when your Da shod my horse, child.”

Nain’s story of the wizard king … But this was Old Wyn, who told stories of his own, and made animals out of scraps of wood. Mared stared at him, trying to read lines of mystery in his familiar face. He went on, “I chose the name after another Mared. She was the wisest person I knew, and the bravest.” He looked at Gil, then continued, “She was the whole of my heart, but King Henry’s soldiers took her and imprisoned her and tried to break her, but they never did.”

Mared did not know what to say. She was not wise—she was too young for that, surely? She did not know if she was brave. She did not know what she would do if the earl’s soldiers took her and tried to make her harm Da or Mam or her brothers. Old Wyn looked back at her, and said, “She was kind, too, my Mared. She always said that was the most important thing.”

“She’s rash, that’s certain,” Da said. Mared looked at her feet.

“This Mared is kind,” Gil said, “and clever, too. And she knows right from wrong.”

“I remember,” Old Wyn said, nodding slowly. “She always brought me food from her Nain. Her name becomes her.”

Mared did not know what to say to that, either. Gil reached down and ruffled her hair with his big hand. “Go back home, now. All’s well here.”

Mared looked over at Da, who nodded. “Go straight home, mind. Don’t wait for me.”

“Yes, Da,” Mared said. Then Gil lifted her up to the trap door, and she climbed back outside.

Mared ran all the way back to her home. No one stirred as she crept back inside and slid back into bed. Her feet were so cold … She meant to stay awake till Da returned, but somehow sleep took her, and when she woke it was morning and Da was making up the fire. He caught her eye and put a finger to his lips. She nodded. It was almost as if she had gone to bed a child but woken as someone more grown up. Da had a secret and he was trusting her with it. Something to do with Gil and Old Wyn. Something to do with Father Dominic and the steward and their behavior towards the village. Neither Gil nor Old Wyn nor even Da had made her promise to keep silent, and the lack of that meant more than anything. They trusted her and she would be worthy of their trust.

Later that morning, Mam took the eggs down to the village and returned with a grim face. “There’s royal soldiers in Penwern,” she said. “A peddler came through and told Wat Miller. He said they’re likely headed this way, what’s more. The king in London is worried about rebellion again and angry still that he never caught their last leader. And the earl’s men are already here.”

Da said, “We’ll deal with that when we have to.” But he spent longer than usual in the forge that day—Mam took him food and would not let any of the children help her—and came back to the house late, long after the moon was high and Mared and her brothers were abed. She heard him whispering to Mam as he undressed for bed. “The fire is out. The rest … We shall have to wait and see.”

The following afternoon, Da went off to work on one of the fences,

taking Mared’s brothers with him. Mam kept Mared close to home, at her spinning. It was a gray, lowering day. Towards midday, it began to snow, in slow heavy flakes. It went on snowing through the night and all of the following day, until the land around Meresbury was an expanse of rolling white, studded with frosted hedges and sparkling trees. The old fort rose up to the west, its ditches marked out by the snow. On the marsh, geese pecked at the ice that covered the shallows, and rose in protesting arcs over the village. “Well, the snow will slow the king’s soldiers,” Mam said, looking out towards where the road should run.

“Midwinter is here,” said Da.

That was Sunday: the family wallowed their way down into the village for church and stood in a chilly row to listen to Father Dominic growl and accuse. There was no stopping to talk in the churchyard outside: rather, the villagers hastened to their homes, hunched against the cold. Mared had to break the ice on the water trough twice that day, so the goat might drink, and her eyes turned over and over to the forge, wondering how Old Wyn was faring. The days were at their shortest: the snow clouds only helped to usher in the night sooner.

Mam woke Mared in the depth of that night. She put a finger to her lips as Mared blinked and began to sit up. Mared hurried back into her outer dress and shoes, then helped Mam with her younger brothers, who were bleary and unsure. Da waited for them by the door. Outside, the snow had finally stopped, and the land lay silent and strange under its coverlet of white. A half-moon hung over towards the western highland, its light turning the snow to silver and gleam. The family followed Da down towards the village, the children stretching their legs to try and step in the marks made by his feet. Mared’s littlest brother slipped and staggered and Mam lifted him up into her arms. There were no sounds, apart from their breath and the slow deep crunch of the snow. Even the goat did not stir as they passed her byre. They made their way, step by slow step, right down to the shadowy line of the town wall. Mared held her breath. The steward had declared no curfew, but the earl’s men still held the gate and they would surely look harshly on any villager caught out at this hour. As they approached, shadowy figures stepped forward and she bit down on her lip to stop herself crying out. But Da was not afraid. He kept on walking and the figures slowly resolved into the familiar forms of Wat Miller and his family. Wat held a close lantern: he nodded to Da and to Mam. Then he reached under his cloak and pulled out a small leather bottle. He handed it to Mared, and said, “Gil gave this to me and told me to ask you to carry it. He told me to tell you that, hopefully, we won’t need it, but if we do, your Nain’s wisdom will guide you.” Then he led his family to stand behind Mared’s. Da turned and began to walk along the line of the wall towards the gate. Every few yards, more shapes joined them—Carlyn and her husband and children, Siwsan and her mother, on and on until almost all the village were with them. They walked in silence, their breath steaming in the night air. Da led them past the gate, which stood stolid and closed, with no sign of the earl’s soldiers. They must be huddled round the fire in the guardhouse. Da walked on down to the waystone at the crossroads. Siwsan wriggled her way up the line to walk next to Mared and caught hold of her hand. “We’re doing the bounds!” Her whisper was an excited rush. “Despite Father Dominic.”

“Winter bounds,” Mared said. Nain had never told a story about this. Midwinter night was for inside, for hearth-fires and quiet times. They did not sing or dance or tell stories outside the inn. And yet … they came to the crossroads, and it seemed that the waystone had somehow grown magically in size. It loomed up towards them, arms outstretched and crowned with a great ring. Mared squeezed Siwsan’s hand. Wat opened the door of the lantern and a beam of yellow light leapt out. The stone resolved into the shape of a man, tall and strong, dressed in a fine brown cloak and wearing a crown of holly. For a moment, Mared was sure that Arddur himself had returned from under the hill. And then the man—the winter king—spoke, and his voice was rich and deep and familiar. Old Wyn, old no more, but proud and upright, his eyes as bright as those of a hawk. He spoke in Welsh, rolling words in praise of God and the saints and the rich green growth of spring. He seemed to need no lantern to light his way. He strode forth boldly and the snow melted under his feet. He led the villagers—at first astonished, then awed, and finally joy-filled—along the line of the river to the far corner of the wood, up along the hedge to the thorn-tree, along the lesser brook to the old ditch, up the ditch to climb the flank of Caer Ogyrfan, following the lines of its banks. As they processed, birds woke in the trees and hedges and raised their voices to praise the spring. Here and there, small buds became apparent on the twigs of saplings. Wyn’s voice—but he was not Wyn, not now; he had thrown off the mantle of the old man and walked instead as he had been in the year of Mared’s birth, the great Welsh king, the king from the west, Owain Glyndŵr, the wizard king—Owain’s voice soothed away the pains of winter and hunger and filled the earth and the air with the glory of nature and of God. It seemed to Mared that she could almost hear the earth itself singing, a low warm rumble beneath the soles of her shoes.

They came to the crest of the old hillfort and Owain raised his arms to the heavens. Moonlight poured down over him, so that he glowed like light through the colored windows of the great church in Penwern. Overhead, the wild geese circled and called. Wat came to stand at the king’s right hand, and Da at his left, both of them likewise bathed in silver light. There were three heroes in many of Nain’s stories. Three golden shoe-makers. Three fair princes. Three brave men. Wat and Da joined their voices to Owain’s and one by one, the villagers joined in.

“Stop this heresy!” The voice was thin and bitter, a twist of bramble beside the bole of a mighty oak, yet somehow it cut through the singing like a sword through flesh. Mared felt her words catch in her throat and stumble to a halt. There, coming up the hill from the village, red-faced and screaming, was Father Dominic, flanked by six of the earl’s men. “I will not permit this! Blasphemy and treason!” The soldiers held spears or bows; as the priest shouted, they levelled them towards the nearest villagers, who drew backwards. There were more villagers than soldiers, but none of them were armed. One by one, the villagers fell back, until the priest and his soldiers stood before Owain, Wat, and Da. “That man,” Father Dominic said, pointing at Owain, “is a traitor. The other two are his allies. Take them.”

Four soldiers stepped forward: the others kept their weapons pointed at the villagers. Mared swallowed hard. This must not be. It could not be. Owain had brought the blessing Father Dominic had refused. She remembered how she and Siwsan had hunted for the secret way into the hill and failed to find it. She remembered Nain’s tale of the wild earl who learnt to fly away with the geese. She slipped her hand free from Siwsan’s and began to wriggle forward through the crowd. All were silent now, save for Owain, who continued to speak in slow soft words, too low for Mared to hear. Her fingers closed on the bottle Gil had sent to her. He had trusted her with this, as he and Da and Owain had trusted her in the inn. He had said she would know what to do.

Father Dominic knew no Welsh. Nor, most likely, did the soldiers. Her eyes met Da’s and he nodded. She took a deep breath and threw the bottle, calling out as she did, “Vrenhin!” King!

Time seemed to slow. The soldiers’ feet stumbled as they tried to step forward. Father Dominic’s voice was washed away by the thunder of Mared’s heart in her ears. Owain raised a hand and caught the bottle. For a moment, he looked down at her and smiled. Then he pulled the cork and drank the contents and cried out in some tongue that Mared did not know.

A heartbeat. Another. Father Dominic gave a strangled cry. His arm—pointing at the three men on the crest of the hill—began to twist and darken. The soldiers stopped, their weapons falling slack from their hands. Owain’s shape, too, began to change, great white wings springing forth from his back, his neck lengthening as he threw his head back to look at the sky. The wild geese swooped, down and down, their wings beating at the heads of the soldiers unt

il they cried out and began to run. Not one villager was touched, though many cowered. Then they leapt upwards, led now by one great white bird about whose neck ran a dark line, like the memory of a crown.

And then they were gone, leaving Wat and Da and Mared standing, gazing at each other, and the villagers, and, where Father Dominic had stood, a twisted knot of gorse. Da stooped and picked something up, then held it out to Mared. A single white flight feather. He said, “Well done, cariad. You merit your name.”

The next summer was warm and generous; yes, and the next four after that. The villagers walked the bounds, led by their new priest, and danced on the green before the inn. But no more was ever heard of the wizard king.

Author’s Note: I have played fast and loose with geography for this story and, to a lesser extent, with history. Meresbury is Oswestry, on the Welsh border, but while it does have an ancient hillfort (associated with Guinevere’s father) it is not normally thought of as one of the places where Arthur sleeps. Owain Glyndŵr did invade it in 1400, and burnt it, but he did not take any care to distinguish Welsh from English tenants. His rebellion peaked by 1406, though his men did raid Shrewsbury (Penwern in this story) in 1408, which I have left out. He was last heard of in around 1412: tradition suggests he was buried somewhere near his family lands in Corwen or Sycharth, or at his daughter’s estate at Kentchurch in Herefordshire. I’ve adapted another border legend, that of the Anglo-Saxon lord Eadric Cild, for the story about the wild geese and the wild hunt. Owain’s wife really was called Mared (which is the Welsh version of Margaret).

A Favor for Lord Bai

Jean Marie Ward

The Ragwitch

The Ragwitch Newt's Emerald

Newt's Emerald Grim Tuesday

Grim Tuesday Sabriel

Sabriel Mister Monday

Mister Monday The Missing

The Missing The Fall

The Fall A Confusion of Princes

A Confusion of Princes Troubletwisters

Troubletwisters Lirael

Lirael Lord Sunday

Lord Sunday Clariel

Clariel Drowned Wednesday

Drowned Wednesday Shade's Children

Shade's Children The Violet Keystone

The Violet Keystone Abhorsen

Abhorsen The Monster

The Monster The Creature in the Case

The Creature in the Case To Hold the Bridge

To Hold the Bridge Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar

Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Above the Veil

Above the Veil Aenir

Aenir Mystery of the Golden Card

Mystery of the Golden Card Superior Saturday

Superior Saturday Sir Thursday

Sir Thursday Castle

Castle Lady Friday

Lady Friday Into Battle

Into Battle Dislocation Space

Dislocation Space Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1)

Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1) Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1

Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1 The Left-Handed Booksellers of London

The Left-Handed Booksellers of London Novel - A Confusion of Princes

Novel - A Confusion of Princes One Beastly Beast

One Beastly Beast A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3

A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3 Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2

Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2 Have Sword, Will Travel

Have Sword, Will Travel Fire Above, Fire Below

Fire Above, Fire Below Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case

Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case The Monster (Troubletwisters)

The Monster (Troubletwisters) Across the Wall

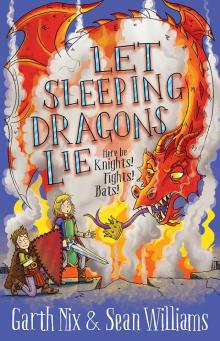

Across the Wall Let Sleeping Dragons Lie

Let Sleeping Dragons Lie![[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/abhorsen_03a_-_across_the_wall_preview.jpg) [Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall

[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall