Novel - A Confusion of Princes Read online

Page 7

But I didn’t get a special mission. All I got back was a truncated version of what I’d heard before.

:Study hard. Await direct instruction <

The next three months were not a lot of fun. Even though the priests do most of the work, it is very wearying to keep up a constant connection to the Imperial Mind. I was tired anyway, for the work at the Academy was designed to test us to the limits of even our engineered capabilities. The extra effort of keeping up that connection meant that I was permanently exhausted and nearly always hovering on the fringe of sleep.

My classmates didn’t try to physically assault me again, at least not all of them at once. Charoz did attack me a few days after the first assault, when I was asleep, but Uncle Krimhiz was listening through my ears and woke me up, so the Imperial Mind saw as well as heard Charoz hit me on the head with a boot, earning himself four demerits and me a nasty bruise.

After that, Charoz changed tactics. Or probably it would be more accurate to say that Jipru suggested a change of tactics. Jipru was very smart, and Charoz wasn’t, so it’s unlikely our brave section leader thought of it himself.

Instead of physical assaults, they turned to small, sneaky means of making things troublesome for me. Like taping my locker shut with an industrial Bitek bond just before the Commandant’s Parade. This tremendous waste of our time took place every week, when we had to march about in ceremonial uniforms, circling the vast subterranean parade ground in front of Huzand, who of course stood on yet another platform and looked down at us. Missing the parade or being in incorrect or incomplete uniform would have earned me at least two demerits. I got around that by cutting the door open with my deintegration wand, but I still received a demerit for damaging equipment, as Charoz reported the damage before I could get it fixed.

They also sabotaged my bed, sawing through its legs so it collapsed when I got in; drew graffiti on the floor next to my locker, which I would be blamed for; and generally tried to get me into trouble.

Though I typically didn’t know who had done these things, my official policy was always to take out my retribution on Charoz. He was the leader, after all. So when they glued my locker shut, I glued his shut. When they sawed through my bed legs, I took off the heels of every pair of his boots, and so on.

It became quite complicated, because naturally they didn’t want to be caught doing whatever they were doing, and I didn’t want to be caught doing what I was doing. So there was a lot of connection and disconnection from the Imperial Mind. They had the advantage of numbers, of course, but often it was only Jipru and Marmro who would follow Charoz’s lead, and though Tyrtho said she was neutral, in fact she often helped me.

I also found a new strategy to help me attack Charoz when I discovered that once I had reached twenty-four demerits, I wasn’t given any more, at least not until the old ones had expired. So I could always be slightly late for every class and in those few minutes wreak havoc on Charoz’s locker, uniforms, or equipment. The others, who were fearful of demerits, always left the barracks on time to make sure they weren’t late for the next lesson, parade, or whatever.

I wondered why I wasn’t given more demerits after I got twenty-four racked up, so I followed some interesting lines of research through the great mass of data the Imperial Mind served up on Naval regulations. The Mind was like that—it often wouldn’t answer a direct question but just give pointers to where the answer might be found and dump a huge amount of unsorted data that had to be actually read or mentally arranged. In this case, I discovered that if a cadet received more than twenty-four demerits every quarter, then there would be an investigation from a higher headquarters. Further research indicated that in my case this investigation would come from the sector admiral, a Prince Elrokhi, who belonged to House Tivand. Presumably an investigation from his headquarters would not at all suit Commandant Huzand.

But there were other punishments in addition to the demerit system, and I was soon introduced to them. The most basic were simply extra drills or lessons to be undertaken in what was notionally a cadet’s free time, and included semiofficial humiliations, like being ordered to scrub floors or to shadow the mekbi trooper guard, doing everything they did—which was mostly standing next to a door all night, occasionally snapping to attention as a Prince came through.

I didn’t mind the extra drills and lessons too much, as I discovered that while I didn’t want to do them, they helped my classwork and drill scores—and I learned things that the other Princes never would.

For example, hanging out with the mekbi troopers turned out to be very educational, though I hated having to salute my treacherous classmates. Charoz and Jipru in particular would often spend an hour just walking backward and forward in front of the guard to make me spring to attention and salute a hundred times.

But it turned out I learned a lot more about the troopers from the interminable guard sessions than from the official direct download lessons like “An Introduction to the Command and Deployment of Standard Mekbi Infantry.” As far as a Prince would know from that data and the accompanying virtual experience, mekbi troopers were not much more than combat automatons who only communicated battlefield information and had no personalities at all. But spending hours and hours with them on duty, marching as one of them, and even (as an additional punishment) lying down with them in their replenishment chambers, I found that there were individual differences and, very importantly, that they did communicate among themselves. In fact they kept up a constant, simple Psitek chatter that most Princes sensed only as an irritating mental humming, a side effect of commanding the troopers.

But the troopers’ mental hum, if you could understand it, contained comments about themselves and the tasks they were undertaking, and constant speculation about how many enemies they would kill before they were killed themselves. Troopers who had already killed enemies were known to all, their serial numbers assuming the place of honored names.

Interestingly, the mekbi troopers assumed they would be killed, and that it was only a matter of time. This didn’t concern them; it was their destiny. As far as I could tell from my eavesdropping, they never considered anything else as being possible. They would do their duty, follow orders, kill and be killed. But they wanted to die good deaths, which meant killing enemies first.

Preferably lots of enemies.

Unfortunately, the cadet under-officers who particularly targeted me soon worked out that I didn’t mind hanging out with the troopers, and they varied my punishments. I annoyed them and got even more punishments by cheerfully accepting whatever they threw at me.

After all, I still thought that I was going to be taken away on some special mission for the Emperor. Except, as each week went past and I got more tired and more harassed, I didn’t get taken away. No special mission was forthcoming, and I started to think that maybe I’d gotten a bit overconfident … again. After all, the arch-priest hadn’t said I’d get a special mission. Only that I shouldn’t join House Jerrazis.

Just to piss me off even more, I had accumulated so many demerits that I was permanently on duty. I couldn’t go and relax in my comfortable off-duty chambers every seventh day, which for the other cadets was a holiday. I had to stay in the barracks doing extra duties, either additional downloads, classes, or drills or once again tailing along with the mekbi troopers as they eternally changed guard.

As this continued and the weeks became months, I came to the reluctant conclusion that I had made a big mistake. I should have taken Huzand’s offer, joined House Jerrazis, and learned to fit in with all the other Princes.

In fact, I was on the brink of asking to see the Commandant and basically groveling to try to make amends when everything changed.

6

THIS BIG, BIG change in my circumstances came in my fifth month at the Academy. I was standing guard with the troopers, listening to the hum of their “2378FDE98X98 slew six rebels” and “9854AAD871F burned down four pirates,” and like I s

aid, I had just about decided that I would ask to see Huzand and see if total subservience would work where rebellion had not.

Changing my miserable life was uppermost in my mind right then because it was a seventh day, and almost every other cadet was on the off-duty side of the base, enjoying their rooms, their mind-programmed servants, their chosen food, and so on. And I was the unnecessary fifth wheel joining a quartet of mekbi troopers guarding a door that didn’t even rate a cadet officer and an extruded desk.

It wasn’t just missing out on relaxation and fun I was worried about. Being confined to barracks also seriously limited my access to Haddad and my priests. I could speak to Haddad via mindspeech, but I was often too tired to do so, and I was also mindful of his earlier advice that other people could potentially listen in. So I still hadn’t discussed the arch-priest with him, what she had said, and so on. My mental conversations with Haddad were always too brief and limited to me asking his advice on how to deal with Charoz’s latest stupid trick, or scheduling my priests, or on some very rare occasions planning how I might let down my constant witnessing for the Imperial Mind so that I could get some real rest.

I was thinking about this, and how I was going to get myself out of the hole that I had largely dug myself, when Haddad’s familiar mental voice suddenly broke in.

:Highness. Procure Psitek protection suit, Mektek communicator rig, and dislocation rifle from <

I was already moving as I sent back a very surprised query.

:What incursion? There’s no alarm!:

:There will be. Hurry!:

The emergency weapon and equipment cache was behind one of the larger metal plates in the Bitek wall, about ten meters away down the corridor. Naturally it was alarmed and monitored in several different ways, and in my sensory overlay there was the warning that any cadet who opened it unnecessarily would face frightful punishments, not just demerits from the Academy but also the Navy proper.

This time I didn’t wonder what else they could do to me. I knew by now that there would be all kinds of things I hadn’t even thought of.

I feared the potential punishment. But I trusted Haddad.

I sent a Psitek command and slapped my hand on the ID plate, which first scanned my palm print and then bit me for a taste of blood. All three tek measures confirmed my identity. The door swung open, alarms went off everywhere in both physical and tek space, and at that same instant I felt a strange sensation in my head as I lost touch with the Imperial Mind, Haddad, and everyone else.

Every Psitek connection had dropped out. I froze in place, my mouth open, finally processing what Haddad had in fact already told me was about to happen.

A Sad-Eye incursion.

As with almost every other subject of importance, I didn’t know much about Sad-Eyes beyond the basic “Enemies of the Empire: An Introduction” lesson a few months back. They were an alien race, masters of their own version of Psitek. Physically they were parasitical brainbugs with a boring-drill snout and really short legs. They drilled into the head of a chosen host, and then from that comfy spot a single Sad-Eye would psychically dominate and control fifty or sixty puppets. They liked humanoids for their host position but could use their Psitek to control almost any living organism that had a developed brain.

These head-drilling monsters were called Sad-Eyes because the only part of a humanoid body they had difficulty controlling were the tear ducts. Sad-Eye hosts and their puppets, if human, tended to look as if they were crying or holding back tears. Which was bad news for ordinary people suffering allergies, or crying at a spaceport or somewhere sensitive like that. Sad-Eyes were greatly feared, and many Princes would order wet-eyed suspects killed as a simple precaution.

Apart from shooting anyone with tears in their eyes from a great distance, the basic Imperial technique for dealing with Sad-Eyes was to turn off every tiny little bit of Psitek, so that they couldn’t suborn it or worm their way into your brain, and then kill them using Mektek or Bitek.

A microsecond after this went through my head, all the auditory alarms in the corridor began to wail and the locker that I had just illegally opened jerked as its automatic opening mechanism cycled again. Farther along the corridor, other doors sprang open, but there was no sudden pounding of feet on the floor of eager cadets coming to pick up weapons and equipment. They were all off duty.

“Ultra Alert! Ultra Alert!” said a voice. “Prepare to repel Sad-Eye boarding force. All cadet officers report to designated battle stations. Other cadets report to your barracks. This is not a drill.”

The voice kept repeating this as I ran into the emergency armory and practically dived into the robing chamber. Nothing happened till I remembered I needed to speak, as all Psitek comms were down.

“Psitek defense suit, Mektek comm gear, flash!” I shouted, raising my arms.

Ports opened and Bitek facilitators aimed their spinnerets. As they wove a Psitek defense suit around me, robot arms positioned a headset over my ears and, with a slight tap, stuck a throat mike just below my Adam’s apple. A few seconds later, the grubs spun up a hood, pulled it closed so that only my mouth, nose, and eyes were free, and retreated back into wherever it was they came from.

I bounded out of the robing chamber, slapped on a nice heavy Mektek armor helmet, grabbed a dislocation rifle from the rack, and checked it, suddenly grateful that a good part of my extra punishment lessons had been spent interminably breaking down and assembling all standard Imperial small arms, a subject that we had not covered in the official curriculum as yet.

Three minutes after Haddad’s original alarm I was suited and armed and back in the corridor. My mekbi guard companions were now really guarding the door, which meant that they had stripped back the Bitek paneling to occupy defensive niches in the rock that gave them some protection and a good field of fire for their energy projectors.

Voices crackled in my ears from the Mektek communicator. Belatedly, I listened to them. There were lots of Princes talking over each other, so it was difficult to sort out. Particularly since I was used to the clarity of mindspeech, where I knew just who was sending.

“It came in riding the supply ship, must be suborned—”

“Don’t recognize the type of vessel, but it’s very heavily armored—”

“It’s got a phased-field drill, they’re boring, we’ve lost guard post five and four in Huzgar, they’re almost through three—”

“How did it get past the system patrol? Achmir must have let it through, curse him; I will protest—”

I recognized that last voice. It was the Commandant, complaining and whining as per usual. I didn’t know who’d spoken before, but what they were saying was a lot more relevant. I was in Huzgar quadrant of the base, and even though I’d lost the Psitek schematic, numerous punishment drills had engraved the base layout on my memory.

Guard post three was directly above my head.

A new voice came on then. A commanding female voice that cut through everyone spouting off whatever was in their heads.

“This is Captain Glemri, Marine Garrison Commander, assuming tactical command. Clear the voicenet now.”

I didn’t know Prince Glemri, though I had seen the Marine specialists around a few times. They commanded the mekbi troopers and were, as far as I could ascertain, looked down on by most of the Naval Princes and by extension, the cadets. Real Navy Princes fought in space, in ships, not with mekbi troopers, who most Princes considered to be an even lower form of life than normal humans, which was kind of unfair since the troopers were superb at what they were made to do, which was kill enemies of the Empire.

Typically, the only voice that didn’t stop talking was Huzand’s, which kept ranting on about Achmir and treachery and so on.

“Commandant, shut up!” barked Glemri. “Any cadet officers in Huzgar, report status.”

There was a deafening silence. After a few seconds, I hesitantly transmitted.

“Uh, I�

�m in Huzgar, sir, level four, guard post two. Cadet Khemri, with four mekbi troopers.”

“Cadet Khemri? Is there a cadet officer there?”

“No, sir. I was on an … extra duty with the troopers.”

“Okay, listen up, Cadet. There isn’t much time—we’ve got a shipload of Sad-Eyes boring down. Get to an emergency armory and get a Psitek protection suit and—”

“I’m suited up and have a dislocation rifle,” I reported.

Glemri sounded surprised.

“You are? Uh, good. About fifteen seconds from now the ceiling is going to come down above your guard post. Pull your troopers back to the Huzgar-Jeresk bulkhead and stop anything trying to come through. Got it?”

“Huzgar-Jeresk bulkhead! Got it—”

I would have added “sir,” but all I could hear now through my headset was the horrible electronic squeal of successful jamming. Which meant that the Sad-Eyes had picked up some puppets who knew at least something about our Mektek.

I ran to the nearest mekbi trooper, intending to tap out an emergency instruction on his chest plate, since these troopers weren’t currently fitted with Mektek comms. But as I got closer, I realized that the low-level Psitek hum of their own talk was still going on, though I could only pick it up when I got close.

Since I could receive it, I could also send. So I sent them a simple message in their own mindspeech.

:Follow me. Glory. Killing. Death:

Technically, it shouldn’t have worked, since there was nothing in it to identify me as their commanding Prince. But as one, they swung out of their defensive wall niches and ran toward me. I spun about and was twenty meters down the corridor when I was blown forward off my feet by the shock wave of something massive smashing through the ceiling behind us.

The Ragwitch

The Ragwitch Newt's Emerald

Newt's Emerald Grim Tuesday

Grim Tuesday Sabriel

Sabriel Mister Monday

Mister Monday The Missing

The Missing The Fall

The Fall A Confusion of Princes

A Confusion of Princes Troubletwisters

Troubletwisters Lirael

Lirael Lord Sunday

Lord Sunday Clariel

Clariel Drowned Wednesday

Drowned Wednesday Shade's Children

Shade's Children The Violet Keystone

The Violet Keystone Abhorsen

Abhorsen The Monster

The Monster The Creature in the Case

The Creature in the Case To Hold the Bridge

To Hold the Bridge Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar

Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Above the Veil

Above the Veil Aenir

Aenir Mystery of the Golden Card

Mystery of the Golden Card Superior Saturday

Superior Saturday Sir Thursday

Sir Thursday Castle

Castle Lady Friday

Lady Friday Into Battle

Into Battle Dislocation Space

Dislocation Space Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1)

Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1) Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1

Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1 The Left-Handed Booksellers of London

The Left-Handed Booksellers of London Novel - A Confusion of Princes

Novel - A Confusion of Princes One Beastly Beast

One Beastly Beast A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3

A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3 Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2

Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2 Have Sword, Will Travel

Have Sword, Will Travel Fire Above, Fire Below

Fire Above, Fire Below Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case

Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case The Monster (Troubletwisters)

The Monster (Troubletwisters) Across the Wall

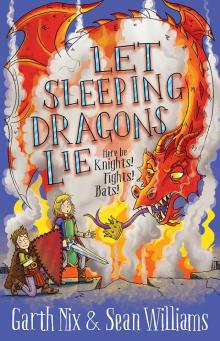

Across the Wall Let Sleeping Dragons Lie

Let Sleeping Dragons Lie![[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/abhorsen_03a_-_across_the_wall_preview.jpg) [Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall

[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall