Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Read online

Page 7

“Ma!” Bai snapped.

“What?” Ma groused, still not bothering to glance in Bai’s direction. “Can’t you see I’m busy?”

Bai yanked off his hat, releasing Gilgamesh’s distinctive curls. He thrust his hand between Ma and his comrades. “I don’t believe we’ve been introduced.”

Ma jumped. “Gilga-a-a …”

Jingxi’s head whipped from side to side, searching for a way to escape. Juanqu hooted, teeth bared in the desperate grin of a monkey in a trap. He patted the air over Bai’s head. As Bai stared, bewildered, Juanqu retracted his hand and formed a fist. Bai instinctively ducked. But Juanqu never threw the punch. He belly-slammed Bai into the cart.

Bai yelped. The cart shook. Its forward struts groaned. Bai grabbed the cart to steady its precious cargo and himself.

The trio ran into the avenue. Crashes, shouts, and curses erupted in their wake.

Bai shook his head and rubbed his thigh. He hadn’t hardened his skin before impact. Nothing felt broken or damp, but from the way it smarted, the bruise promised to be spectacular.

Still, the afternoon was looking up. He had solved the mystery of the tax notice. Better yet, Juanqu’s cannon gut had knocked a mooncake and several cream buns into the bed of the cart. Cracked and squashed, they couldn’t be sold. Hu’s discerning clientele would never accept damaged goods. Bai’s karma would hardly suffer if he prevented them from going to waste. A Neo-Confucian might even consider eating them an act of merit. All the same, he checked the alley and the avenue to make sure he didn’t get caught.

A distant roar reverberated along the gray brick canyon of the shopping street. It grew louder as Bai listened—a bestial sound, born of many voices, which spanned the aural spectrum from guttural bellows to furious screeches. Only one mortal animal possessed such a range. Only one raged in packs. War band, gang fight, or riot? Bai couldn’t say. He couldn’t see the source of the clamor. He only knew the humans who created it were getting closer.

Despite who and what he was, Bai felt an atavistic shiver ruffle phantom spines along the back of his neck. This was how the first humans exterminated the mastodons and other giant beasts of the Last Age. Massed together, their mingled screams rending ears and minds, the puny hairless apes drove those noble animals into pits lined with sharpened sticks. Dispatching them with clubs and rocks, the humans cooked their victims where they died and reveled in the gore. But that was before dragons took to the sky, before humans learned to herd grass-eaters, before the apes civilized themselves.

They weren’t that civilized. A part of them never forgot what they were capable of.

Somewhere in the distance, someone shouted: “Run!” Dozens, maybe hundreds took up the cry. Run!

Run!

RUNNNN!

Pedestrians scattered. Mounted riders wheeled and galloped east, barely outpacing the frightened citizens charging up the pavement behind them. The multitude rushed toward Bai like a tsunami. The carts, displays, and street-side tables were tossed aside. They shattered against storefronts or were crushed in the stampede. Broken sign boards leapt into the air like flotsam at high tide. The noise was indescribable—cracking wood, booming feet, the howl of hell wolves, rapid-fire shrieks of rage—and the cause was still unknown, still too distant to be identified.

It didn’t matter. The panic was infectious. Overwhelming. Bai retreated to the cart in a mindless quest for cover. He had been pursued by humans singly and in groups. He had faced mortal danger in a hundred different forms. But he had never been caught in a mob. The sight, the sound, the sheer mass of humanity triggered something deep within his dragon brain, something primitive and scared, from a time when even his kind were prey.

Ma, Jingxi, and Juanqu burst into the alley. Bai opened his mouth to croak a warning. Before he could remember words, Ma pulled to a stop.

“Wait!” he cried. “We need ammunition. You boys take the yoke. I’ll handle the artillery.”

Ma turned to the cart. Bai stood between him and the ramp. Ma flinched, then stabbed a finger at the dazed dragon’s chest. “You! Lead, follow, or get out of the way!”

A woman shrilled over the din of the avenue, “They’re in the alley! The alley next to the bookseller!”

Bai leapt onto the back of the cart and pulled Ma up behind him. “You load. I’ll throw.”

He flipped the backboard into place and shot the latches. Ma yelled, “Mush!”

“I wish we had a horse,” Jingxi whined.

Juanqu whinnied, and the cart rocketed forward. A lane opened to the right. The cart sheared into the turn as their pursuers barreled into the alley they left behind.

Bai, Ma, and the contents of the baskets flopped to the side. Ma whipped upright and shoved pastry at Bai. The cart lurched and slid, jounced and juddered. Bracing himself against the cab, Bai didn’t try to compensate. With so many targets, he didn’t need to aim.

The motley rabble on their tail was just a small riot, not the army of his fears, but the numbers were bad enough. Eight roaring bruisers marked by broken noses, docked ears, and various sinister scars manned the poles of an aristocrat’s red sedan chair. In the wider streets and intersections they plied it like a garden roller, trampling anything in their path. In the narrower alleys and passageways, they wielded it like a giant scythe. The two liveried chairmen caught between the poles struggled to keep the cab level as the vehicle careened from side to side.

Behind the chair, Bai glimpsed another four thugs and the crested helms of two city guardsmen. A flat-faced, middle-aged woman wearing the black coat of an entertainer harried the brutes from the rear. Mother Pan Pan, he presumed. Three black-coated young women flew in her wake. They might have been pretty when their features weren’t scrunched around feral yowls. A lucky spray of cream buns reduced the din and forced the pursuers to fall back, but only for a moment.

“Faster!” Bai yelled. He grabbed another round of baked goods. “They’re gaining on us!”

A fresh volley of sesame seed balls splattered against the dust-clouded sedan chair and its bearers. Black bean paste bled into eyes and cheeks. Speeding feet skidded on jellied water chestnut squares and the lotus paste hearts of mooncakes. The sedan chair shook harder but kept coming.

From somewhere in the depths of the crowd Bai heard a plaintive cry. “My cart! Help! Police! They stole my cart!”

Bai shared the deliveryman’s pain. A little piece of his soul died with every bun and biscuit he threw. He would never eat them now. If the mob caught up with him, he might never eat again. He reached for more pastry.

“It’s empty,” Ma shouted as the cart plunged from a relatively bright side street into a high-sided, tunnel-like alley.

“There’s more,” Bai assured him. “Get the basket. Hold for ‘go.’ I want to take out the chair.”

“Say, you’re all right!”

Bai grinned. The ersatz Gilgamesh was still grinning when he shouted, “Go!”

The large, square basket rushed toward the lead thug’s face. He yanked his pole to the left. The basket bounced off his shoulder and dropped to the ground. The man behind him stumbled over the hamper. Struggling to keep his balance, he threw his weight onto the torqued pole. The wood splintered with a sound like artillery fire.

The chair crew staggered, nearly dropping their burden. The remaining pursuers jammed up behind them. For an instant, Bai thought the pastry cart was saved. Then the lead thug heaved the remains of the broken pole on his shoulder and resumed the chase.

Bai reached for more baked goods.

“Just a sec,” Ma said. “The last batch is on the floor.”

“Shouldn’t there be two?” Bai could have sworn he saw three baskets when he jumped in the cart.

He glanced at the teetering shelves. The number of baskets was the least of their problems. They were running into a trap. The street at the end of the alley was blocked off with sawhorses and building supplies. Scaffolding fronted a large, jagged gap in the tall gray brick wall a

cross the street. Workmen swarmed the cordoned area, stirring mortar, laying courses, and ferrying supplies.

Bai shouted, “Stop!” as Ma hollered, “Damn the construction, full speed ahead!” Jingxi and Juanqu surged forward.

They were going to die. Hardening his skin until it resembled his natural hide, Bai jumped from the cart. He landed in a patch of mud near the alley wall. With no time and no place to run, he curled his arms over his head and fell to his knees.

The human tide roared past. A terrible crash reverberated from the end of the alley. The yelling grew louder. He covered his ears. Wait, he wouldn’t be caught dead in the afterlife with human ears. He must still be alive. Yes, he was breathing. The alley stank of trash and piss. He risked opening his eyes. Lurching to his feet, he struggled to comprehend the scene playing out in the wrecked construction site.

Mother Pan Pan and company were fighting the construction crew. They appeared to have forgotten the original objects of their wrath, who were nowhere in sight. A richly-robed walrus of a man girdled in an ostentatious silver belt shouted threats from the sidelines, while the deliveryman tried to free his cart from the ruins of the scaffolding.

The red sedan chair had run aground against a mortar tub. As Bai watched, the chairmen hoisted a tiny old woman from the battered cab. She was gowned in the rich crimson silk reserved for dukes and their immediate family. Gold combs bedizened with jade, emeralds and pearls glittered in the coils of her unnaturally black hair. She jabbed her gold-headed cane toward the melee, and the chairmen dutifully supported her doddering steps in that direction. For one mad instant Bai wondered if he should stop them. The lady was the oldest non-magical human Bai had ever seen. Then she took out the nearest bruiser with a single blow to the head. Her withered lips stretched in a triumphant grin.

A steamy chuckle burbled up Bai’s throat. Then another.

The deliveryman kicked the tumbled scaffolding poles and started cursing, quickly proving himself a master of the obscene. A bricklayer locked under a bulky guardsman’s arm flailed at the guard’s backside without connecting. Bai couldn’t tell if the cop was trying to strike back or reaching for the helmet bouncing from foot to foot like a cuju ball.

Bai laughed aloud. This was funnier than a Nanxi operetta.

The helmet’s progress drew Bai’s attention to something—three somethings, in fact—worming through the mud. The authors of this mayhem belly-crawled between the legs of the crowd, stealthily working their way toward the alley.

Bai was tempted to let them escape. No longer worried about what was happening at the bar or tearing across the back alleys of Nanjing in fear for his life, he realized they were funny. If they had been actors in a play, he would have paid good silver coins to see them.

But the reason Ma, Jingxi, and Juanqu were in this fix was because they wanted to rob Gilgamesh. Bai could not allow their crime to go unpunished, not if he wished to retain the demigod’s favor.

The trio scuttled closer to Bai. Backlit by the sky over the street, he couldn’t see their eyes. But their thrust-back shoulders, thrust-forward chins, their wide elbows and fisted hands made their intentions plain. Bai’s Gilgamesh was as bedraggled as everyone else and the odds against him were three to one. Juanqu woofed and jogged in place, pumping his arms like a boxer in a play.

Bai snickered, not bothering to mask the smoke of his amusement. No one else in the street paid any attention. The four of them could have been alone in the world—the perfect circumstance for what Bai had in mind.

His snout extended and his lips pulled back from the white-fanged death of a dragon’s smile. His eyes shifted from brown to their natural golden amber. Their pupils went from round to pointed ovals. Smoke and vapor wreathed mighty serpentine coils with scales the color of thunderheads. His belly was hammered silver. His talons glittered, as sharp and long as Imperial swords.

He shifted again, devolving into human once more. But instead of a bear-like western barbarian, he stood before them in the guise of his self-appointed tutor, Li Lao—master sorcerer, restrainer of dragons, and the newest mandarin in the Department of Rites. Admittedly, Bai improved a little on the original. He gave the old scarecrow his own imposing height and dressed him in a rich violet-blue silk robe befitting the badge of office stitched to its front. But the fringe of hair rolled under his black-winged scholar’s hat, the jug ears, the wrinkles, and the (blessedly) wispy beard were all Lao.

Bai’s smooth transition from fellow fugitive to dragon to mandarin was too much for the threesome’s tiny primate brains to grasp. They fainted. Their bodies dropped like so many trees in the forest, which no one seemed to hear.

This presented a problem. The young dragon had many natural gifts. In his true form he could fly, spit lightning, and weather the fiercest winter storm. He could transform into the perfect image of any human he had ever met. In every form, he was preternaturally strong, a master of all languages, aware of ambient magic, and a collector of treasure. But there was no way he could haul those three clowns before a magistrate all by himself. Time to put the city guardsmen to the use the Emperor intended. He took a deep breath.

“Silence!” His dragon voice resounded in the closed space like a mighty Shang bell.

All the conscious humans froze. They were indeed a sorry lot, especially the senior of the two guardsmen. In addition to losing his helmet and being covered in muck, the buttons on his regulation quilted vest had popped all the way to his collar. The front panels spread in an equilateral triangle around a decidedly non-regulation paunch. The knots of gray hair dribbling over his shoulders were as stringy as old Lao’s. But damned if he didn’t manage a smart salute.

“Sir! Who do I have the honor of addressing, sir?”

“Li Lao, mandarin of the fifth degree, Department of Rites.” Bai pointed to his badge with a hematite-tipped nail only slightly shorter than his corresponding talon. This was another improvement on the original, who pared his nails like a common artisan. “What is the meaning of this commotion?”

Several people spoke at once. Bai raised his hand and unfurled his claws. The humans gaped. A few blanched. More to the point, they all shut up.

“You.” He pointed to the deliveryman. “Why are you swearing?”

“Those crooks stole my cart and ruined my pastries,” he sobbed. “My boss will never understand. I’ll lose my job.”

Having so few wits to recover, Ma, Jingxi, and Juanqu were already trying to crawl away. Bai pinned the hem of Ma’s tunic in place with his shoe. Ma tried to pull free. Bai fixed the threesome with an amber-eyed glance and slowly shook his head. They meekly pressed their foreheads against the ground.

“Stop whining,” Mother Pan Pan said. “Your cart’s under there somewhere—and you got two guards who saw the whole thing. Those morons ruined my best girls.”

Remembering the speed, agility, and ferocity the young women displayed earlier, Bai couldn’t imagine how.

“I hired those guys as hairdressers. I felt sorry for them, all right!” Mother Pan Pan snapped in response to Bai’s disbelieving stare. “The city took their bar and everything in it. They told me they used to take care of the Widow Cheng’s hair. Her hair always looked good, so I figured I’d give them a chance. What harm could it do? What harm could it do?” She giggled maniacally. “Let’s see!”

Mother Pan Pan stalked toward the young women. The former furies trembled like baby birds at her approach. She snatched their coiffures from their heads, revealing three pates as slick and naked as a serpent’s egg.

The workmen gasped. Several of Mother Pan Pan’s thugs grimaced in what looked like sympathy.

A small, imperious sniff broke the horrified silence. “And you call yourself an abbess,” the scarlet-gowned dowager interjected in a surprisingly firm voice. “You wouldn’t know a business opportunity if it smacked you on the nose. Dress those girls in orange and say they’re Buddhist nuns. They’ll be a sensation. You’ll have every noble and official in the city vying t

o pollute them. How do you think Wu Mei got to be Empress Wu Zetian?”

“Carts! Hair!” the man in the silver belt bawled. He flung his arms wide. “What about my wall? That crash destroyed two wagonloads of supplies—and the crew is paid by the hour.”

“You can afford it,” the dowager and the deliveryman shot back. She added, “You don’t hear me complaining about my chair.”

Surprisingly, the construction workers agreed. They chorused: “Yeah!” “The old tightwad!” “You tell ‘im!”

Boosting his voice to compete, Bai said, “These are serious accusations. Do you three have anything to say in your defense?”

Ma sat back on his haunches. “We’re sorry, your honor. We never meant to hurt anyone. We were only trying to get enough money to open a new bar. We spent our whole lives working at Cheng’s Bar. It’s all we know.”

Lao’s old man eyebrows crawled up Bai’s forehead. Indeed! His new favorite comedians had worked in their aunt’s bar—a bar the Director of Entertainment Licenses and Revenue described as an institution and implied was well-run until they took over the helm. The wyrm of an idea began to turn in his brain. He addressed the senior constable. “Do you have anything you wish to add concerning the character of these men?”

“The Chengs and Feng Jingxi aren’t career criminals, if that’s what you mean.”

Bai gestured for him to continue. “They went broke, because they made lousy beer—not that it was any surprise,” the constable said. “Their aunt served the worst beer in town.”

“Why you …” Juanqu sputtered. “Auntie Cheng made great beer! She was the most popular hostess in Nanjing!”

The constable snorted. “The Widow Cheng was the fourth-most ruthless information broker in town. She had the dirt on everybody. The government couldn’t afford to let her fail.”

The Ragwitch

The Ragwitch Newt's Emerald

Newt's Emerald Grim Tuesday

Grim Tuesday Sabriel

Sabriel Mister Monday

Mister Monday The Missing

The Missing The Fall

The Fall A Confusion of Princes

A Confusion of Princes Troubletwisters

Troubletwisters Lirael

Lirael Lord Sunday

Lord Sunday Clariel

Clariel Drowned Wednesday

Drowned Wednesday Shade's Children

Shade's Children The Violet Keystone

The Violet Keystone Abhorsen

Abhorsen The Monster

The Monster The Creature in the Case

The Creature in the Case To Hold the Bridge

To Hold the Bridge Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar

Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Above the Veil

Above the Veil Aenir

Aenir Mystery of the Golden Card

Mystery of the Golden Card Superior Saturday

Superior Saturday Sir Thursday

Sir Thursday Castle

Castle Lady Friday

Lady Friday Into Battle

Into Battle Dislocation Space

Dislocation Space Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1)

Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1) Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1

Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1 The Left-Handed Booksellers of London

The Left-Handed Booksellers of London Novel - A Confusion of Princes

Novel - A Confusion of Princes One Beastly Beast

One Beastly Beast A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3

A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3 Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2

Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2 Have Sword, Will Travel

Have Sword, Will Travel Fire Above, Fire Below

Fire Above, Fire Below Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case

Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case The Monster (Troubletwisters)

The Monster (Troubletwisters) Across the Wall

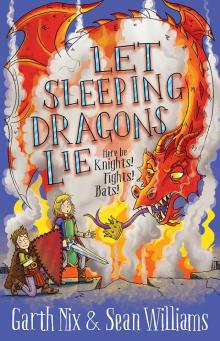

Across the Wall Let Sleeping Dragons Lie

Let Sleeping Dragons Lie![[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/abhorsen_03a_-_across_the_wall_preview.jpg) [Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall

[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall