Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1 Read online

Page 2

The troop rode toward the duo at a canter, slowing to a walk as they drew nearer and their horses began to balk as they scented the battlemounts. Hereward raised his hand in greeting and the cornet shouted a command, the column extending to a line, then halting within an easy pistol shot. Hereward watched the troop sergeant, who rode forward beyond the line for a better look, then wheeled back at speed toward the cornet. If the Dercians were to break their oath, the sergeant would fell her officer first.

But the sergeant halted without drawing a weapon and spoke to the cornet quietly. Hereward felt a slight easing of his own breath, though he showed no outward sign of it and did not relax. Nor did Mister Fitz withdraw his hand from under his robes. Hereward knew that his companion’s moulded papier-mâché fingers held an esoteric needle, a sliver of some arcane stuff that no human hand could grasp with impunity.

The cornet listened and spoke quite sharply to the sergeant, turning his horse around so that he could make his point forcefully to the troopers as well. Hereward only caught some of the words, but it seemed that despite his youth, the officer was rather more commanding than he had expected, reminding the Dercians that their oaths of employment overrode any private or societal vendettas they might wish to undertake.

When he had finished, the cornet shouted, “Dismount! Sergeant, walk the horses!”

The officer remained mounted, wheeling back to approach Hereward. He saluted as he reined in a cautious distance from the battlemounts, evidently not trusting either the creatures’ blinkers and mouth-cages or his own horse’s fears.

“Welcome to Shûme!” he called. “I am Cornet Misolu. May I ask your names and direction, if you please?”

“I am Sir Hereward of the High Pale, artillerist for hire.”

“And I am Fitz, also of the High Pale, aide de camp to Sir Hereward.”

“Welcome . . . uh . . . sirs,” said Misolu. “Be warned that war has been declared upon Shûme, and all who pass through must declare their allegiances and enter certain . . . um . . .”

“I believe the usual term is ‘undertakings’,” said Mister Fitz.

“Undertakings,” echoed Misolu. He was very young. Two bright spots of embarrassment burned high on his cheekbones, just visible under the four bars of his lobster-tailed helmet, which was a little too large for him, even with the extra padding, some of which had come a little undone around the brow.

“We are free lances, and seek hire in Shûme, Cornet Misolu,” said Hereward. “We will give the common undertakings if your city chooses to contract us. For the moment, we swear to hold our peace, reserving the right to defend ourselves should we be attacked.”

“Your word is accepted, Sir Hereward, and . . . um . . .”

“Mister Fitz,” said Hereward, as the puppet said merely, “Fitz.”

“Mister Fitz.”

The cornet chivvied his horse diagonally closer to Hereward, and added, “You may rest assured that my Dercians will remain true to their word, though Sergeant Xikoliz spoke of some feud their . . . er . . . entire people have with you.”

The curiosity in the cornet’s voice could not be easily denied, and spoke as much of the remoteness of Shûme as it did of the young officer’s naïveté.

“It is a matter arising from a campaign several years past,” said Hereward. “Mister Fitz and I were serving the Heriat of Jhaqa, who sought to redirect the Dercian spring migration elsewhere than through her own prime farmlands. In the last battle of that campaign, a small force penetrated to the Dercians’ rolling temple and . . . ah . . . blew it up with a specially made petard. Their godlet, thus discommoded, withdrew to its winter housing in the Dercian steppe, wreaking great destruction among its chosen people as it went.”

“I perceive you commanded that force, sir?”

Hereward shook his head.

“No, I am an artillerist. Captain Kasvik commanded. He was slain as we retreated—another few minutes and he would have won clear. However, I did make the petard, and . . . Mister Fitz assisted our entry to the temple and our escape. Hence the Dercians’ feud.”

Hereward looked sternly at Mister Fitz as he spoke, hoping to make it clear that this was not a time for the puppet to exhibit his tendency for exactitude and truthfulness. Captain Kasvik had in fact been killed before they even reached the rolling temple, but it had served his widow and family better for Kasvik to be a hero, so Hereward had made him one. Only Mister Fitz and one other survivor of the raid knew otherwise.

Not that Hereward and Fitz considered the rolling temple action a victory, as their intent had been to force the Dercian godlet to withdraw a distance unimaginably more vast than the mere five hundred leagues to its winter temple.

The ride to the city was uneventful, though Hereward could not help but notice that Cornet Misolu ordered his troop to remain in place and keep watch, while he alone escorted the visitors, indicating that the young officer was not absolutely certain the Dercians would hold to their vows.

There was a zigzag entry through the earthwork ramparts, where they were held up for several minutes in the business of passwords and responses (all told aside in quiet voices, Hereward noted with approval), their names being recorded in an enormous ledger and passes written out and sealed allowing them to enter the city proper.

These same passes were inspected closely under lanternlight, only twenty yards farther on by the guards outside the city gate—which was closed, as the sun had finally set. However, they were admitted through a sally port and here Misolu took his leave, after giving directions to an inn that met Hereward’s requirements: suitable stabling and food for the battlemounts; that it not be the favourite of the Dercians or any other of the mercenary troops who had signed on in preparation for Shûme’s impending war; and fine food and wine, not just small beer and ale. The cornet also gave directions to the citadel, not that this was really necessary as its four towers were clearly visible, and advised Hereward and Fitz that there was no point going there until the morning, for the governing council was in session and so no one in authority could hire him until at least the third bell after sunrise.

The streets of Shûme were paved and drained, and Hereward smiled again at the absence of the fetid stench so common to places where large numbers of people dwelt together. He was looking forward to a bath, a proper meal and a fine feather bed, with the prospect of well-paid and not too onerous employment commencing on the morrow.

“There is the inn,” remarked Mister Fitz, pointing down one of the narrower side streets, though it was still broad enough for the two battlemounts to stride abreast. “The sign of the golden barleycorn. Appropriate enough for a city with such fine farmland.”

They rode into the inn’s yard, which was clean and wide and did indeed boast several of the large iron-barred cages used to stable battlemounts complete with meat canisters and feeding chutes rigged in place above the cages. One of the four ostlers present ran ahead to open two cages and lower the chutes, and the other three assisted Hereward to unload the panniers. Mister Fitz took his sewing desk and stood aside, the small rosewood-and-silver box under his arm provoking neither recognition nor alarm. The ostlers were similarly incurious about Fitz himself, almost certainly evidence that self-motivated puppets still came to entertain the townsfolk from time to time.

Hereward led the way into the inn, but halted just before he entered as one of the battlemounts snorted at some annoyance. Glancing back, he saw that it was of no concern, and the gates were closed, but in halting he had kept hold of the door as someone else tried to open it from the other side. Hereward pushed to help and the door flung open, knocking the person on the inside back several paces against a table, knocking over an empty bottle that smashed upon the floor.

“Unfortunate,” muttered Mister Fitz, as he saw that the person so inconvenienced was not only a soldier, but wore the red sash of a junior officer, and was a woman.

“I do apolog—” Hereward began to say. He stopped, not only because the woman was t

alking, but because he had looked at her. She was as tall as he was, with ash-blond hair tied in a queue at the back, her hat in her left hand. She was also very beautiful, at least to Hereward, who had grown up with women who ritually cut their flesh. To others, her attractiveness might be considered marred by the scar that ran from the corner of her left eye out toward the ear and then cut back again toward the lower part of her nose.

“You are clumsy, sir!”

Hereward stared at her for just one second too long before attempting to speak again.

“I am most—”

“You see something you do not like, I think?” interrupted the woman. “Perhaps you have not served with females? Or is it my face you do not care for?”

“You are very beautiful,” said Hereward, even as he realized it was entirely the wrong thing to say, either to a woman he had just met or an officer he had just run into.

“You mock me!” swore the woman. Her blue eyes shone more fiercely, but her face paled, and the scar grew more livid. She clapped her broad-brimmed hat on her head and straightened to her full height, with the hat standing perhaps an inch over Hereward. “You shall answer for that!”

“I do not mock you,” said Hereward quietly. “I have served with men, women . . . and eunuchs, for that matter. Furthermore, tomorrow morning I shall be signing on as at least colonel of artillery, and a colonel may not fight a duel with a lieutenant. I am most happy to apologize, but I cannot meet you.”

“Cannot or will not?” sneered the woman. “You are not yet a colonel in Shûme’s service, I believe, but just a mercenary braggart.”

Hereward sighed and looked around the common room.

Misolu had spoken truly that the inn was not a mercenary favourite. But there were several officers of Shûme’s regular service or militia, all of them looking on with great attention.

“Very well,” he snapped. “It is foolishness, for I intended no offence. When and where?”

“Immediately,” said the woman. “There is a garden a little way behind this inn. It is lit by lanterns in the trees, and has a lawn.”

“How pleasant,” said Hereward. “What is your name, madam?”

“I am Lieutenant Jessaye of the Temple Guard of Shûme. And you are?”

“I am Sir Hereward of the High Pale.”

“And your friends, Sir Hereward?”

“I have only this moment arrived in Shûme, Lieutenant, and so cannot yet name any friends. Perhaps someone in this room will stand by me, should you wish a second. My companion, whom I introduce to you now, is known as Mister Fitz. He is a surgeon—among other things—and I expect he will accompany us.”

“I am pleased to meet you, Lieutenant,” said Mister Fitz. He doffed his hat and veil, sending a momentary frisson of small twitches among all in the room save Hereward.

Jessaye nodded back but did not answer Fitz. Instead she spoke to Hereward.

“I need no second. Should you wish to employ sabres, I must send for mine.”

“I have a sword in my gear,” said Hereward. “If you will allow me a few minutes to fetch it?”

“The garden lies behind the stables,” said Jessaye. “I will await you there. Pray do not be too long.”

Inclining her head but not doffing her hat, she stalked past and out the door.

“An inauspicious beginning,” said Fitz.

“Very,” said Hereward gloomily. “On several counts. Where is the innkeeper? I must change and fetch my sword.”

****

The garden was very pretty. Railed in iron, it was not gated, and so accessible to all the citizens of Shûme. A wandering path led through a grove of lantern-hung trees to the specified lawn, which was oval and easily fifty yards from end to end, making the centre rather a long way from the lanternlight, and hence quite shadowed. A small crowd of persons who had previously been in the inn were gathered on one side of the lawn. Lieutenant Jessaye stood in the middle, naked blade in hand.

“Do be careful, Hereward,” said Fitz quietly, observing the woman flex her knees and practice a stamping attack ending in a lunge. “She looks to be very quick.”

“She is an officer of their temple guard,” said Hereward in a hoarse whisper. “Has their god imbued her with any particular vitality or puissance?”

“No, the godlet does not seem to be a martial entity,” said Fitz. “I shall have to undertake some investigations presently, as to exactly what it is—”

“Sir Hereward! Here at last.”

Hereward grimaced as Jessaye called out. He had changed as quickly as he could, into a very fine suit of split-sleeved white showing the yellow shirt beneath, with gold ribbons at the cuffs, shoulders and front lacing, with similarly cut bloomers of yellow showing white breeches, with silver ribbons at the knees, artfully displayed through the side-notches of his second-best boots.

Jessaye, in contrast, had merely removed her uniform coat and stood in her shirt, blue waistcoat, leather breeches and unadorned black thigh boots folded over below the knee. Had the circumstances been otherwise, Hereward would have paused to admire the sight she presented and perhaps offer a compliment.

Instead he suppressed a sigh, strode forward, drew his sword and threw the scabbard aside.

“I am here, Lieutenant, and I am ready. Incidentally, is this small matter to be concluded by one or perhaps both of us dying?”

“The city forbids duels to the death, Sir Hereward,” replied Jessaye. “Though accidents do occur.”

“What, then, is to be the sign for us to cease our remonstrance?”

“Blood,” said Jessaye. She flicked her sword towards the onlookers. “Visible to those watching.”

Hereward nodded slowly. In this light, there would need to be a lot of blood before the onlookers could see it. He bowed his head but did not lower his eyes, then raised his sword to the guard position.

Jessaye was fast. She immediately thrust at his neck, and though Hereward parried, he had to step back. She carried through to lunge in a different line, forcing him back again with a more awkward parry, removing all opportunity for Hereward to riposte or counter. For a minute they danced, their swords darting up, down and across, clashing together only to move again almost before the sound reached the audience.

In that minute, Hereward took stock of Jessaye’s style and action. She was very fast, but so was he, much faster than anyone would expect from his size and build, and, as always, he had not shown just how truly quick he could be. Jessaye’s wrist was strong and supple, and she could change both attacking and defensive lines with great ease. But her style was rigid, a variant of an old school Hereward had studied in his youth.

On her next lunge—which came exactly where he anticipated—Hereward didn’t parry but stepped aside and past the blade. He felt her sword whisper by his ribs as he angled his own blade over it and with the leading edge of the point, he cut Jessaye above the right elbow to make a long, very shallow slice that he intended should bleed copiously without inflicting any serious harm.

Jessaye stepped back but did not lower her guard. Hereward quickly called out, “Blood!”

Jessaye took a step forward and Hereward stood ready for another attack. Then the lieutenant bit her lip and stopped, holding her arm toward the lanternlight so she could more clearly see the wound. Blood was already soaking through the linen shirt, a dark and spreading stain upon the cloth.

“You have bested me,” she said, and thrust her sword point first into the grass before striding forward to offer her gloved hand to Hereward. He too grounded his blade, and took her hand as they bowed to each other.

A slight stinging low on his side caused Hereward to look down. There was a two-inch cut in his shirt, and small beads of blood were blossoming there. He did not let go Jessaye’s fingers, but pointed at his ribs with his left hand.

“I believe we are evenly matched. I hope we may have no cause to bicker further?”

“I trust not,” said Jessaye quietly. “I regret the incident.

Were it not for the presence of some of my fellows, I should not have cavilled at your apology, sir. But you understand . . . a reputation is not easily won, nor kept . . .”

“I do understand,” said Hereward. “Come, let Mister Fitz attend your cut. Perhaps you will then join me for small repast?”

Jessaye shook her head.

“I go on duty soon. A stitch or two and a bandage are all I have time for. Perhaps we shall meet again.”

“It is my earnest hope that we do,” said Hereward. Reluctantly, he opened his grasp. Jessaye’s hand lingered in his palm for several moments before she slowly raised it, stepped back and doffed her hat to offer a full bow. Hereward returned it, straightening up as Mister Fitz hurried over, carrying a large leather case as if it were almost too heavy for him, one of his standard acts of misdirection, for the puppet was at least as strong as Hereward, if not stronger.

“Attend to Lieutenant Jessaye, if you please, Mister Fitz,” said Hereward. “I am going back to the inn to have a cup . . . or two . . . of wine.”

“Your own wound needs no attention?” asked Fitz as he set his bag down and indicated to Jessaye to sit by him.

“A scratch,” said Hereward. He bowed to Jessaye again and walked away, ignoring the polite applause of the onlookers, who were drifting forward either to talk to Jessaye or gawp at the blood on her sleeve.

“I may take a stroll,” called out Mister Fitz after Hereward. “But I shan’t be longer than an hour.”

****

Mister Fitz was true to his word, returning a few minutes after the citadel bell had sounded the third hour of the evening. Hereward had bespoken a private chamber and was dining alone there, accompanied only by his thoughts.

“The god of Shûme,” said Fitz, without preamble. “Have you heard anyone mention its name?”

Hereward shook his head and poured another measure from the silver jug with the swan’s beak spout. Like many things he had found in Shûme, the knight liked the inn’s silverware.

“They call their godlet Tanesh,” said Fitz. “But its true name is Pralqornrah-Tanish-Kvaxixob.”

The Ragwitch

The Ragwitch Newt's Emerald

Newt's Emerald Grim Tuesday

Grim Tuesday Sabriel

Sabriel Mister Monday

Mister Monday The Missing

The Missing The Fall

The Fall A Confusion of Princes

A Confusion of Princes Troubletwisters

Troubletwisters Lirael

Lirael Lord Sunday

Lord Sunday Clariel

Clariel Drowned Wednesday

Drowned Wednesday Shade's Children

Shade's Children The Violet Keystone

The Violet Keystone Abhorsen

Abhorsen The Monster

The Monster The Creature in the Case

The Creature in the Case To Hold the Bridge

To Hold the Bridge Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar

Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Above the Veil

Above the Veil Aenir

Aenir Mystery of the Golden Card

Mystery of the Golden Card Superior Saturday

Superior Saturday Sir Thursday

Sir Thursday Castle

Castle Lady Friday

Lady Friday Into Battle

Into Battle Dislocation Space

Dislocation Space Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1)

Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1) Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1

Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1 The Left-Handed Booksellers of London

The Left-Handed Booksellers of London Novel - A Confusion of Princes

Novel - A Confusion of Princes One Beastly Beast

One Beastly Beast A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3

A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3 Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2

Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2 Have Sword, Will Travel

Have Sword, Will Travel Fire Above, Fire Below

Fire Above, Fire Below Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case

Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case The Monster (Troubletwisters)

The Monster (Troubletwisters) Across the Wall

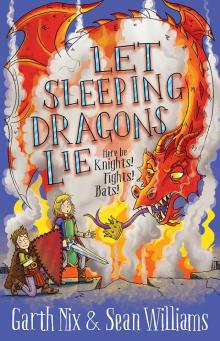

Across the Wall Let Sleeping Dragons Lie

Let Sleeping Dragons Lie![[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/abhorsen_03a_-_across_the_wall_preview.jpg) [Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall

[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall