Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1 Read online

Page 3

“As difficult to say or spell, I wager,” said Hereward. “I commend the short form, it shows common sense. What of it?”

“It is on the list,” said Fitz.

Hereward bit the edge of pewter cup and put it down too hard, slopping wine upon the table.

“You’re certain? There can be no question?”

Fitz shook his head. “After I had doctored the young woman, I went down to the lake and took a slide of the god’s essence—it was quite concentrated in the water, easily enough to yield a sample. You may compare it with the record, if you wish.”

He proffered a finger-long inch-wide strip of glass that was striated in many different bands of colour. Hereward accepted it reluctantly, and with it a fat, square book that Fitz slid across the table. The book was open at a hand-tinted colour plate, the illustration showing a sequence of colour bands.

“It is the same,” agreed the knight, his voice heavy with regret. “I suppose it is fortunate we have not yet signed on, though I doubt they will see what we do as being purely a matter of defence.”

“They do not know what they harbor here,” said Fitz.

“It is a pleasant city.” said Hereward, taking up his cup again to take a large gulp of the slightly sweet wine. “In a pretty valley. I had thought I could grow more than accustomed to Shûme—and its people.”

“The bounty of Shûme, all its burgeoning crops, its healthy stock and people, is an unintended result of their godlet’s predation upon the surrounding lands,” said Fitz. “Pralqornrah is one of the class of cross-dimensional parasites that is most dangerous. Unchecked, in time it will suck the vital essence out of all the land beyond its immediate demesne. The deserts of Balkash are the work of a similar being, over six millennia. This one has only been embedded here for two hundred years—you have seen the results beyond this valley.”

“Six millennia is a long time,” said Hereward, taking yet another gulp. The wine was strong as well as sweet, and he felt the need of it. “A desert might arise in that time without the interference of the gods.”

“It is not just the fields and the river that Pralqornrah feeds upon,” said Fitz. “The people outside this valley suffer too. Babes unborn, strong men and women declining before their prime . . . this godlet slowly sucks the essence from all life.”

“They could leave,” said Hereward. The wine was making him feel both sleepy and mulish. “I expect many have already left to seek better lands. The rest could be resettled, the lands left uninhabited to feed the godlet. Shûme could continue as an oasis. What if another desert grows around it? They occur in nature, do they not?”

“I do not think you fully comprehend the matter,” said Fitz. “Pralqornrah is a most comprehensive feeder. Its energistic threads will spread farther and faster the longer it exists here, and it in turn will grow more powerful and much more difficult to remove. A few millennia hence, it might be too strong to combat.”

“I am only talking,” said Hereward, not without some bitterness. “You need not waste your words to bend my reason. I do not even need to understand anything beyond the salient fact: this godlet is on the list.”

“Yes,” said Mister Fitz. “It is on the list.”

Hereward bent his head for a long, silent moment. Then he pushed his chair back and reached across for his sabre. Drawing it, he placed the blade across his knees. Mister Fitz handed him a whetstone and a small flask of light, golden oil. The knight oiled the stone and began to hone the sabre’s blade. A repetitive rasp was the only sound in the room for many minutes, till he finally put the stone aside and wiped the blade clean with a soft piece of deerskin.

“When?”

“Fourteen minutes past the midnight hour is optimum,” replied Mister Fitz. “Presuming I have calculated its intrusion density correctly.”

“It is manifest in the temple?”

Fitz nodded.

“Where is the temple, for that matter? Only the citadel stands out above the roofs of the city.”

“It is largely underground,” said Mister Fitz. “I have found a side entrance, which should not prove difficult. At some point beyond that there is some form of arcane barrier—I have not been able to ascertain its exact nature, but I hope to unpick it without trouble.”

“Is the side entrance guarded? And the interior?”

“Both,” said Fitz. Something about his tone made Hereward fix the puppet with a inquiring look.

“The side door has two guards,” continued Fitz. “The interior watch is of ten or eleven . . . led by the Lieutenant Jessaye you met earlier.”

Hereward stood up, the sabre loose in his hand, and turned away from Fitz.

“Perhaps we shall not need to fight her . . . or her fellows.”

Fitz did not answer, which was answer enough.

****

The side door to the temple was unmarked and appeared no different than the other simple wooden doors that lined the empty street, most of them adorned with signs marking them as the shops of various tradesmen, with smoke-grimed night lamps burning dimly above the sign. The door Fitz indicated was painted a pale violet and had neither sign nor lamp.

“Time to don the brassards and make the declaration,” said the puppet. He looked up and down the street, making sure that all was quiet, before handing Hereward a broad silk armband five fingers wide. It was embroidered with sorcerous thread that shed only a little less light than the smoke-grimed lantern above the neighbouring shop door. The symbol the threads wove was one that had once been familiar the world over but was now unlikely to be recognized by anyone save an historian . . . or a god.

Hereward slipped the brassard over his left glove and up his thick coat sleeve, spreading it out above the elbow. The suit of white and yellow was once again packed, and for this expedition the knight had chosen to augment his helmet and buff coat with a dented but still eminently serviceable back- and breastplate, the steel blackened by tannic acid to a dark grey. He had already primed, loaded and spanned his two wheel-lock pistols, which were thrust through his belt; his sabre was sheathed at his side; and a lozenge-sectioned, armour-punching bodkin was in his left boot.

Mister Fitz wore his sewing desk upon his back, like a wooden backpack. He had already been through its numerous small drawers and containers and selected particular items that were now tucked into the inside pockets of his coat, ready for immediate use.

“I wonder why we bother with this mummery,” grumbled Hereward. But he stood at attention as Fitz put on his own brassard, and the knight carefully repeated the short phrase uttered by his companion. Though both had recited it many times, and it was clear as bright type in their minds, they spoke carefully and with great concentration, in sharp contrast to Hereward’s remark about mummery.

“In the name of the Council of the Treaty for the Safety of the World, acting under the authority granted by the Three Empires, the Seven Kingdoms, the Palatine Regency, the Jessar Republic and the Forty Lesser Realms, we declare ourselves agents of the Council. We identify the godlet manifested in this city of Shûme as Pralqornrah-Tanish-Kvaxixob, a listed entity under the Treaty. Consequently, the said godlet and all those who assist it are deemed to be enemies of the World and the Council authorizes us to pursue any and all actions necessary to banish, repel or exterminate the said godlet.”

Neither felt it necessary to change this ancient text to reflect the fact that only one of the three empires was still extant in any fashion; that the seven kingdoms were now twenty or more small states; the Palatine Regency was a political fiction, its once broad lands under two fathoms of water; the Jessar Republic was now neither Jessar in ethnicity nor a republic; and perhaps only a handful of the Forty Lesser Realms resembled their antecedent polities in any respect. But for all that the states that had made it were vanished or diminished, the Treaty for the Safety of the World was still held to be in operation, if only by the Council that administered and enforced it.

“Are you ready?” asked Fitz.

/>

Hereward drew his sabre and moved into position to the left of the door. Mister Fitz reached into his coat and drew out an esoteric needle. Hereward knew better than to try to look at the needle directly, but in the reflection of his blade, he could see a four-inch line of something intensely violet writhe in Fitz’s hand. Even the reflection made him feel as if he might at any moment be unstitched from the world, so he angled the blade away.

At that moment, Fitz touched the door with the needle and made three short plucking motions. On the last motion, without any noise or fuss, the door wasn’t there anymore. There was only a wood-panelled corridor leading down into the ground and two very surprised temple guards, who were still leaning on their halberds.

Before Hereward could even begin to move, Fitz’s hand twitched across and up several times. The lanterns on their brass stands every six feet along the corridor flickered and flared violet for a fraction of a second. Hereward blinked, and the guards were gone, as were the closest three lanterns and their stands.

Only a single drop of molten brass, no bigger than a tear, remained. It sizzled on the floor for a second, then all was quiet.

The puppet stalked forward, cupping his left hand over the needle in his right, obscuring its troublesome sight behind his fingers. Hereward followed close behind, alert for any enemy that might be resistant to Fitz’s sorcery.

The corridor was a hundred yards long by Hereward’s estimation, and slanted sharply down, making him think about having to fight back up it, which would be no easy task, made more difficult as the floor and walls were damp, drops of water oozing out between the floorboards and dripping from the seams of the wall panelling. There was cold, wet stone behind the timber, Hereward knew. He could feel the cold air rippling off it, a chill that no amount of fine timber could cloak.

The corridor ended at what appeared from a distance to be a solid wall, but closer to was merely the dark back of a heavy tapestry. Fitz edged silently around it, had a look, and returned to beckon Hereward in.

There was a large antechamber or waiting room beyond, sparsely furnished with a slim desk and several well-upholstered armchairs. The desk and chairs each had six legs, the extra limbs arranged closely at the back, a fashion Hereward supposed was some homage to the godlet’s physical manifestation. The walls were hung with several tapestries depicting the city at various stages in its history.

Given the depth underground and the proximity of the lake, great efforts must have been made to waterproof and beautify the walls, floor and ceiling, but there was still an army of little dots of mould advancing from every corner, blackening the white plaster and tarnishing the gilded cornices and decorations.

Apart from the tapestry-covered exit, there were three doors. Two were of a usual size, though they were elaborately carved with obscure symbols and had brass, or perhaps even gold, handles. The one on the wall opposite the tapestry corridor was entirely different: it was a single ten-foot-by-six-foot slab of ancient marble veined with red lead, and it would have been better situated sitting on top of a significant memorial or some potentate’s coffin.

Mister Fitz went to each of the carved doors, his blue tongue flickering in and out, sampling the air.

“No one close,” he reported, before approaching the marble slab. He actually licked the gap between the stone and the floor, then sat for a few moments to think about what he had tasted.

Hereward kept clear, checking the other doors to see if they could be locked. Disappointed in that aim as they had neither bar nor keyhole, he sheathed his sabre and carefully and quietly picked up a desk to push against the left door and several chairs to pile against the right. They wouldn’t hold, but they would give some warning of attempted ingress.

Fitz chuckled as Hereward finished his work, an unexpected noise that made the knight shiver, drop his hand to the hilt of his sabre, and quickly look around to see what had made the puppet laugh. Fitz was not easily amused, and often not by anything Hereward would consider funny.

“There is a sorcerous barrier,” said Fitz. “It is immensely strong but has not perhaps been as well thought-out as it might have been. Fortuitously, I do not even need to unpick it.”

The puppet reached up with his left hand and pushed the marble slab. It slid back silently, revealing another corridor, this one of more honest bare, weeping stone, rapidly turning into rough-hewn steps only a little way along.

“I’m afraid you cannot follow, Hereward,” said Fitz. “The barrier is conditional, and you do not meet its requirements. It would forcibly—and perhaps harmfully—repel you if you tried to step over the lintel of this door. But I would ask you to stay here in any case, to secure our line of retreat. I should only be a short time if all goes well. You will, of course, know if all does not go well, and must save yourself as best you can. I have impressed the ostlers to rise at your command and load our gear, as I have impressed instructions into the dull minds of the battlemounts—”

“Enough, Fitz! I shall not leave without you.”

“Hereward, you know that in the event of my—”

“Fitz. The quicker it were done—”

“Indeed. Be careful, child.”

“Fitz!”

But the puppet had gone almost before that exasperated single word was out of Hereward’s mouth.

It quickly grew cold with the passage below open. Chill, wet gusts of wind blew up and followed the knight around the room, no matter where he stood. After a few minutes trying to find a spot where he could avoid the cold breeze, Hereward took to pacing by the doors as quietly as he could. Every dozen steps or so he stopped to listen, either for Fitz’s return or the sound of approaching guards.

In the event, he was midpace when he heard something. The sharp beat of hobnailed boots in step, approaching the left-hand door.

Hereward drew his two pistols and moved closer to the door. The handle rattled, the door began to move and encountered the desk he had pushed there. There was an exclamation and several voices spoke all at once. A heavier shove came immediately, toppling the desk as the door came partially open.

Hereward took a pace to the left and fired through the gap. The wheel locks whirred, sparks flew, then there were two deep, simultaneous booms, the resultant echoes flattening down the screams and shouts in the corridor beyond the door, just as the conjoining clouds of blue-white smoke obscured Hereward from the guards, who were already clambering over their wounded or slain companions.

The knight thrust his pistols back through his belt and drew his sabre, to make an immediate sweeping cut at the neck of a guard who charged blindly through the smoke, his halberd thrust out in front like a blind man’s cane. Man and halberd clattered to the floor. Hereward ducked under a halberd swing and slashed the next guard behind the knees, at the same time picking up one edge of the desk and flipping it upright in the path of the next two guards. They tripped over it, and Hereward stabbed them both in the back of the neck as their helmets fell forward, left-right, three inches of sabre point in and out in an instant.

A blade skidded off Hereward’s cuirass and would have scored his thigh but for a quick twist away. He parried the next thrust, rolled his wrist and slashed his attacker across the stomach, following it up with a kick as the guard reeled back, sword slack in his hand.

No attack—or any movement save for dulled writhing on the ground—followed. Hereward stepped back and surveyed the situation. Two guards were dead or dying just beyond the door. One was still to his left. Three lay around the desk. Another was hunched over by the wall, his hands pressed uselessly against the gaping wound in his gut, as he moaned the god’s name over and over.

None of the guards was Jessaye, but the sound of the pistol shots at the least would undoubtedly bring more defenders of the temple.

“Seven,” said Hereward. “Of a possible twelve.”

He laid his sabre across a chair and reloaded his pistols, taking powder cartridges and shot from the pocket of his coat and a ramrod from unde

r the barrel of one gun. Loaded, he wound their wheel-lock mechanisms with a small spanner that hung from a braided-leather loop on his left wrist.

Just as he replaced the pistols in his belt, the ground trembled beneath his feet, and an even colder wind came howling out of the sunken corridor, accompanied by a cloying but not unpleasant odour of exotic spices that also briefly made Hereward see strange bands of colour move through the air, the visions fading as the scent also passed.

Tremors, scent and strange visions were all signs that Fitz had joined battle with Pralqornrah-Tanish-Kvaxixob below. There could well be other portents to come, stranger and more unpleasant to experience.

“Be quick, Fitz,” muttered Hereward, his attention momentarily focused on the downwards passage.

Even so, he caught the soft footfall of someone sneaking in, boots left behind in the passage. He turned, pistols in hand, as Jessaye stepped around the half-open door. Two guards came behind her, their own pistols raised.

Before they could aim, Hereward fired and, as the smoke and noise filled the room, threw the empty pistols at the trio, took up his sabre and jumped aside.

Jessaye’s sword leapt into the space where he’d been. Hereward landed, turned and parried several frenzied stabs at his face, the swift movement of their blades sending the gun smoke eddying in wild roils and coils. Jessaye pushed him back almost to the other door. There, Hereward picked up a chair and used it to fend off several blows, at the same time beginning to make small, fast cuts at Jessaye’s sword arm.

Jessaye’s frenzied assault slackened as Hereward cut her badly on the shoulder near her neck, then immediately after that on the upper arm, across the wound he’d given her in the duel. She cried out in pain and rage and stepped back, her right arm useless, her sword point trailing on the floor.

Instead of pressing his attack, the knight took a moment to take stock of his situation.

The two pistol-bearing guards were dead or as good as, making the tally nine. That meant there should only be two more, in addition to Jessaye, and those two were not immediately in evidence.

The Ragwitch

The Ragwitch Newt's Emerald

Newt's Emerald Grim Tuesday

Grim Tuesday Sabriel

Sabriel Mister Monday

Mister Monday The Missing

The Missing The Fall

The Fall A Confusion of Princes

A Confusion of Princes Troubletwisters

Troubletwisters Lirael

Lirael Lord Sunday

Lord Sunday Clariel

Clariel Drowned Wednesday

Drowned Wednesday Shade's Children

Shade's Children The Violet Keystone

The Violet Keystone Abhorsen

Abhorsen The Monster

The Monster The Creature in the Case

The Creature in the Case To Hold the Bridge

To Hold the Bridge Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar

Second Round: A Return to the Ur-Bar Above the Veil

Above the Veil Aenir

Aenir Mystery of the Golden Card

Mystery of the Golden Card Superior Saturday

Superior Saturday Sir Thursday

Sir Thursday Castle

Castle Lady Friday

Lady Friday Into Battle

Into Battle Dislocation Space

Dislocation Space Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1)

Sabriel (Old Kingdom Book 1) Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1

Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again shamf-1 The Left-Handed Booksellers of London

The Left-Handed Booksellers of London Novel - A Confusion of Princes

Novel - A Confusion of Princes One Beastly Beast

One Beastly Beast A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3

A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet shamf-3 Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2

Beyond the Sea Gates of the Scholar Pirates of Sarsköe shamf-2 Have Sword, Will Travel

Have Sword, Will Travel Fire Above, Fire Below

Fire Above, Fire Below Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case

Nicholas Sayre and the Creature in the Case The Monster (Troubletwisters)

The Monster (Troubletwisters) Across the Wall

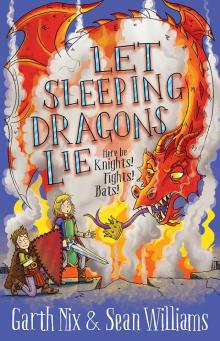

Across the Wall Let Sleeping Dragons Lie

Let Sleeping Dragons Lie![[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/12/abhorsen_03a_-_across_the_wall_preview.jpg) [Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall

[Abhorsen 03a] - Across the Wall